Letter 159

| Date | 17/29 November 1869 |

|---|---|

| Addressed to | Mily Balakirev |

| Where written | Moscow |

| Language | Russian |

| Autograph Location | Saint Petersburg (Russia): National Library of Russia (ф. 834, ед. хр. 11, л. 24–28) |

| Publication | Переписка М. А. Балакирева и П. И. Чайковского (1868-1891) [1912], p. 44–48 П. И. Чайковский. Полное собрание сочинений, том V (1959), p. 184–187 Милий Алексеевич Балакирев. Воспоминания и письма (1962), p. 142–145 |

Text and Translation

| Russian text (original) |

English translation By Luis Sundkvist |

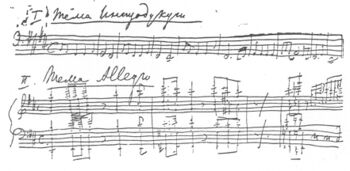

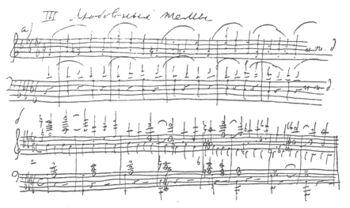

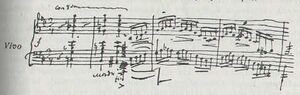

17 ноября 1869 г[ода] Милый друг! Очень был рад получить наконец от Вас известия о Ваших концертах, так как здесь слухи о них ходили самые противоречащие. Признаюсь (хоть и то хорошо, что расходы покрыты), я ожидал от Вашего хвалёного города, что он отнесётся к Вам с большею горячностью. Не могу удержаться, чтобы не вообразить того, как бы поступила Москва, если б, напр[имер], с Н. Рубинштейном было поступлено так, как с Вами. Да, в его концертах, устроенных бы в пику какой-нибудь Алёне, яблоку некуда было бы упасть. А ведь Вы должны быть для Петербурга то, что Рубинштейн для Москвы; т. е. Вы оба работаете и тратите жизнь и силы на дело общее, а не своё. Воображаю себе, сколько бы у меня испортилось крови, если бы я жил теперь в Вашем отвратительном болоте. Нет! С каждым днём убеждаюсь я, что жить спокойно можно только в Москве; уж одно то, что наша первопрестольная не оскверняется паршивой газеткой Фаминцына! Вы смеялись над нашей публикой за то, что она, ничего не смысля, ездит в концерты Музыкального общества. А знаете ли, что, несмотря на 4 представления итальянской оперы в неделю, у нас уж теперь 900 членов, а к концу сезона будет 1200? Ах, Господи, что за счастье жить в Москве! Или вот Вам ещё петербургская штука. В прошлом апреле Гедеонов через своего секретаря писал мне, чтоб я представил партитуру оперы к 1 сентября. Я её отправил к Фёдорову в начале августа, прося уведомить о получении и о том, пойдёт ли опера и если пойдёт, то когда именно? Прошёл август, сентябрь и половина октября без всякого ответа; в половине октября пишу к Гедеонову умилительное и почтительное письмо, прося исполнить обещание или известить положительно, что опера нейдёт. Опять ответа никакого. На днях один господин говорит мне, что он из верных источников знает, что уж оперу мою начали разучивать. Пишу к Сетову, и сегодня наконец получаю известие от него, что в Петербургской дирекции даже никто и не знал, что моя опера лежит там с первых чисел августа! Повторяю: человек может быть истинно счастлив, лишь живя в богохранимом граде, где Царь-колокол лежит и т. д. Вы, вероятно, немножко удивитесь, узнав, что Увертюра моя не только готова, но уже переписывается, чтобы быть исполненной в одном из следующих концертов. Вам я пришлю её только в таком случае, когда, услышав её здесь, я найду в ней хоть какие-нибудь достоинства. Теперь, когда она готова, но ещё не исполнена, я менее, чем когда-либо, знаю, чего она стоит; знаю только, что она, во всяком случае, не настолько дурна, чтоб я опасался осрамиться ею здесь, в Москве (в чудной, невозмутимо спокойной, лишённой разных Фаминцыных и Серовых Москве!). Посылаю Вам в конце письма главные темы—и больше ничего покамест; а потом пришлю переписанную для Вас партитуру с посвящением, — разумеется, Вам. Рубинштейн просит передать Вам, что он не согласен играть моё Scherzo, так как он его совершенно позабыл, а вновь учить некогда. Он держится прежней программы, т. е. 1) Ласковский, 2) Morceau favori du président de la Казённая палата и 3) Geliebtes Stück von Herrn Albrecht. Касательно дела Альбрехта я очень удивляюсь, что Вы с некоторой горделивостью даже не признаёте возможным, чтобы члены Вашей компании сочинили для него по маленькому хорику. Я полагаю, что нет ничего унизительного для Бородина или Мусоргского набросать на 3 или 4 голоса песенку; ни Шуман, ни Бетховен этим не гнушались. Если ж к тому ж они этим могут оказать большую услугу честному и милейшему собрату по искусству, — то отказ с их стороны будет не более как фанфаронство. Впрочем, я думаю, что Корсаков так мил и добр (остальных я меньше знаю) и к тому же так высокодаровит, что подобная мелочно-самолюбивая выходка и в ум ему не придёт, и Вы напрасно взялись заранее предугадывать, как он отнесётся к предложению Альбрехта. Про Вас же и говорить нечего; я знаю, что при Ваших занятиях Вам некогда заниматься пустяками, — но сочинённый для Бесплатной школы Männerchor Вы, наверно, отдадите нашему немцу и Вашему восторженному поклоннику. Как бы то ни было, а за присылку имён и адресов крепко Вас благодарю. Был здесь проездом Антон Рубинштейн; 5 декабря он играет у нас в концерте и даёт, кроме того, свой концерт. Мои русские песни на этой неделе будут готовы, и я немедленно пошлю Вам и милому Ник[олаю] Андр[еевичу] по экземпляру. Юргенсон очень удивлён, что Вы спрашиваете, берёт ли он «Пиданду»?. Он дело это считал поконченным и только удивлялся, что Вы так долго не шлёте ему подлинника Крепко обнимаю Вас и прошу кланяться хорошенько Ник[олаю] Андр[еевичу] и остальным членам горделивой компании. П. Чайковский Затем идёт беготня в стиле того маленького образчика, что, помните, Вы мне прислали? Если увидите Бесселя, намекните ему, что мне очень нужны деньги, и я бы очень рад был получить за работу! |

17 November 1869 Dear friend! I was very glad to receive at last news from you about your concerts, since the most contradictory rumours about them have been circulating here [1]. I must confess (although it is good that you have managed to cover your expenses) that I had expected your much-vaunted city to support you more passionately. I cannot resist imagining how Moscow would act if, say, N. Rubinstein were to be treated in the same way that you have been treated. Why, at the concerts that he would then start organizing to spite some old Alyona there wouldn't be room to swing a cat! [2] Now, you must surely be for Petersburg what Rubinstein is for Moscow—that is, both of you work and use up your lives and energy for the common cause rather than to advance your own interests. I can imagine how my blood would start boiling if I were now living in your revolting swamp [3]. No! With every day that passes I become more convinced that only in Moscow can one live calmly. Suffice it to say that our old capital isn't defiled by Famintsyn's rotten little newspaper! [4] You made fun of our public for going to the Musical Society's concerts without having a clue about music. Well, did you know that, in spite of the four performances of Italian Opera every week, we now have 900 members, and by the end of the season this figure should have risen to 1,200? [5] Ah, Lord, what bliss it is to live in Moscow! Here's another Petersburg anecdote for you: this April, Gedeonov, through his secretary, wrote to me asking that I submit the score of my opera by 1 September [6]. I sent it to Fyodorov at the start of August, asking him to acknowledge receipt, as well as to inform me whether the opera would be staged, and if so, when exactly? [7]. August passed by, then September, then the first half of October, and still there was no reply. In mid-October I wrote a pathetic and respectful letter to Gedeonov, asking him either to keep his promise or to inform me unambiguously that the opera wasn't going to be staged [8]. Again there was no reply whatsoever. A few days ago one gentleman told me that he knew from reliable sources that they had already started rehearsing my opera. I wrote to Setov, and today at last I received a note from him informing me that no one at the Petersburg Directorate had even been aware that my score had been lying there since the start of August! I repeat: a person can only be truly happy if he is living in the god-protected city where rests the Tsar Bell, and so on [9]. You will probably be a bit surprised to find out that my overture is not only ready, but is already being copied so that it can be performed at one of the next concerts. I will send it to you only if, after hearing it for myself here, I can find at least some merits in it. Now that the overture is ready, but has not been performed yet, I know even less than before what its worth may be. All I know is that in any case it is not so bad as to make me afraid of covering myself with shame here, in Moscow (in this wonderful, imperturbably calm city which is free of the likes of Famintsyn and Serov!). At the end of the letter I am sending you the main themes, but no more for the time being. Later I will send you a copy of the score with a dedication to you, of course. Rubinstein asks me to tell you that he isn't willing to play my "Scherzo", since he has forgotten it completely and doesn't have the time to study it again. He is sticking to the original programme, that is: 1) Laskovsky, 2) Morceau favori du président of the Revenue Department, and 3) Geliebtes Stück of Herr Albrecht [10]. With regard to Albrecht's project, I am very surprised that you dismiss, with a certain haughtiness, the very idea that the members of your company should each write a little chorus for him [11]. I think it would surely not be humiliating for Borodin or Musorgsky to sketch a little song for three or four voices. Neither Schumann nor Beethoven disdained writing such pieces. If, moreover, in this way they can do a big service for an honest and likeable artistic colleague, then a refusal on their part would be no more than a bit of swaggering. However, I think that Korsakov is so nice and kind (I don't know the others so well), and furthermore so highly gifted, that it would never occur to him to make such a pettishly vain gesture, and that you are wrong in your prediction as to how he will respond to Albrecht's request [12]. This doesn't apply to you, of course: I know that, with all your obligations, you don't have any time to occupy yourself with trifles, but I do hope that you will hand over the chorus for men's voices which you composed for the Free Music School to our German, who is a fervent admirer of yours. Be that as may be, I thank you warmly for having sent the names and addresses. Anton Rubinstein stopped briefly here on his way through. On 5th December he will be playing in one of our concerts, as well as giving his own concert. My Russian songs will be ready this week, and I will immediately send you and dear Nikolay Andreyevich a copy each [13]. Jurgenson is very surprised about your asking whether he is willing to publish "Pidanda"? [14]. He considered this matter to have been settled and is puzzled that you haven't sent him the original in all this time. I embrace you firmly and ask you to send my kind regards to Nikolay Andreyevich and the other members of your haughty company. P. Tchaikovsky After that comes a scrambling in the style of that brief sample which you sent me (do you remember?) [15]. If you see Bessel, could you drop him a hint that I am in desperate need of money, and that I would be very glad to receive the payment for my work! [16] |

Notes and References

- ↑ In his letter to Tchaikovsky of 12/24 November 1869 (the letter to which Tchaikovsky is replying here), Balakirev had written about the first Free Music School concerts of the season in Saint Petersburg. Balakirev had thrown all his energy into these concerts after his unjust dismissal earlier that year from the post of chief conductor of the Russian Musical Society concerts in the Imperial capital. See Balakirev's letter in Милий Алексеевич Балакирев. Воспоминания и письма (1962), p. 141–142.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky is referring to the circumstances of Balakirev's dismissal from the RMS, which had been engineered by the Society's patroness, Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna, and various conservative-minded musicians in Saint Petersburg who disapproved of Balakirev's programming of contemporary works (Russian and foreign) in the Society's concerts. Alyona (Алёна) is the rustic variant of the name Yelena, and Tchaikovsky uses it as an ironic allusion to the Grand Duchess in the context of his half-jesting association of Moscow with good old Russian traditions.

- ↑ Saint Petersburg was built on what was originally marshland, hence Tchaikovsky's description of the Imperial capital as a "swamp".

- ↑ The Saint Petersburg-based review newspaper The Musical Season (Музыкальный сезон), whose editor was the music critic and professor of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, Aleksandr Sergeyevich Famintsyn (1841–1896), and which numbered among its contributors Aleksandr Serov, Nikolay Solovyev, and Herman Laroche. Tchaikovsky and Balakirev rejected this newspaper because of its academic slant and Famintsyn's hostility towards the works of young Russian composers.

- ↑ Despite the popularity of the Italian Opera Company in Moscow (which had acquired the right to put on performances at the Bolshoi Theatre on four out of six evenings every week), there was also a growing interest in symphonic and chamber music, as reflected in the rising membership numbers of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky had to submit the score of his opera Undina to the Saint Petersburg office of the Directorate of Imperial Theatres, which was then headed by Stepan Gedeonov.

- ↑ See Letter 144 to Pavel Fyodorov, 6/18 August 1869.

- ↑ See Letter 154 to Stepan Gedeonov, 12/24 October 1869.

- ↑ The Tsar Bell is a huge bell, cast in the eighteenth century, which since 1836 has been on display on a pedestal in the Moscow Kremlin. Tchaikovsky is poking fun here at Slavophile notions of Moscow as the spiritual heartland of Russia.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky is discussing the programme of the fourth Free Music School concert of the season, which was to take place in Saint Petersburg on 30 November/12 December 1869, and at which Nikolay Rubinstein would play Liszt's Piano Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, a Berceuse by Ivan Fyodorovich Laskovsky (1799–1855), Tchaikovsky's Romance, Op. 5, and Balakirev's Islamey (first performance). Tchaikovsky's Romance was the favourite piano piece of Nikolay Yakovlevich Makarov (1822–1892), an official in the Ministry of Finances with whom Tchaikovsky was acquainted. Tchaikovsky's friend and colleague Karl Albrecht liked Balakirev's oriental fantasy Islamey very much: see Letter 151 to Balakirev, 2/14 October 1869.

- ↑ See Letter 156 to Balakirev, 28 October/9 November 1869, in which Tchaikovsky explained that Karl Albrecht was compiling an anthology of choral pieces written using the numerical method of Chevé, for which he was keen to have contributions from the composers of the "Mighty Handful" as well. Tchaikovsky refers to them as "your company" in the above letter, because Balakirev was the guiding spirit of this circle of composers.

- ↑ In his letter to Tchaikovsky of 12/24 November 1869, Balakirev explained that some years back he had composed a chorus for men's voices for the Free Music School, but that none of the members of his circle had written any piece of that kind and would hardly be inclined to. Nevertheless, he had provided Tchaikovsky with the full names and addresses of the composers of the "Mighty Handful" so that Albrecht could send them his request. See Balakirev's letter in: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев. Воспоминания и письма (1962), p. 142.

- ↑ Book 2 of the Fifty Russian Folksongs, harmonized and arranged for piano duet by Tchaikovsky.

- ↑ i.e. Balakirev's oriental fantasia Islamey. Vladimir Stasov's brother Dmitry, who made copies of Tchaikovsky's letters to Balakirev, added the following note to his copy of this letter: "I wrote to M. A. Balakirev and asked him what the word 'Pidanda' in P. I. Tchaikovsky's letter of 2 October [O.S.] means, and he replied to me on 1 October 1907 [O.S.], explaining that 'this is the opening word of a Tartar song which the actor De Lazari (an Armenian) often sang in Moscow, and which I used as the second theme in Islamey'". Quoted from Милий Алексеевич Балакирев. Воспоминания и письма (1962), p. 190.

- ↑ In his letter to Tchaikovsky of 4/16 October 1869, Balakirev had sketched some bars of "a fierce Allegro [depicting] sabre blows" representing the feud between the Montague and Capulet families, which he suggested to Tchaikovsky as the opening for the Romeo and Juliet overture. See Balakirev's letter in: Милий Алексеевич Балакирев. Воспоминания и письма (1962), p. 137. Here is Balakirev's sketch:

.

.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky's arrangement for piano duet of Anton Rubinstein's characteristic musical picture Ivan the Terrible, which he had undertaken at the request of the Saint Petersburg-based publisher Vasily Bessel.