Italian Capriccio and Nikolay Kuznetsov: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

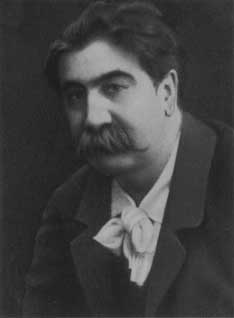

{{picture|file=Nikolay Kuznetsov.jpg|caption='''Nikolay Kuznetsov''' (1850-1929)}} | |||

Russian artist (b. 2/14 December 1850 at Stepanovka, [[Odessa]] province; d. February 1929 at Sarajevo), born '''''Nikolay Dmitriyevich Kuznetsov''''' (Николай Дмитриевич Кузнецов). | |||

The son of a landowner from Kherson province, Kuznetsov was a student at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, where he was awarded three silver medals. In 1881, he began to tour widely exhibiting his works, frequently travelling abroad. | |||

The | |||

== | ==Tchaikovsky and Kuznetsov== | ||

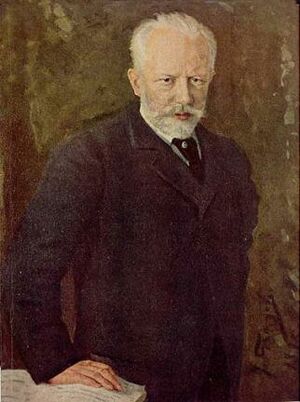

In [[Odessa]] in January 1893 he painted the only contemporary portrait of Tchaikovsky, which now hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery in [[Moscow]]. | |||

A few days after leaving [[Odessa]], Tchaikovsky wrote to [[Vladimir Makovsky]]: | |||

{{quote|I made the acquaintance of the painter ''N. D. Kuznetsov'', who wished to paint my portrait, and this he carried out with exceptional success, as others have said and as I, too, think. Those citizens of [[Odessa]] who came to look at this portrait during the sittings expressed their extraordinary delight, amazement, and joy over the fact that such a splendid work of art was being painted in their city. The portrait was painted rather hurriedly, and that is why it may possibly not have the desired finish in the details, but in terms of its expression, lifelikeness, and authenticity it really is remarkable" <ref name="note1"/>.}} | |||

{{picture|file=Kuznetsov Portrait 1893.jpg|caption=[[Nikolay Kuznetsov]]'s portrait of the composer, 1893}} | |||

Tchaikovsky also praised this portrait in a letter to his brother [[Modest]]: "In [[Odessa]] the painter '' Kuznetsov'' painted a really ''astonishing'' portrait of me. I hope that he still has enough time to send it to the ''peredvizhniki'' exhibition" <ref name="note2"/>. In his biography of the composer, [[Modest]] said the following about Kuznetsov's portrait: | |||

The | {{quote|This portrait is now in the Tretyakov Gallery. The artist, who was not familiar with Pyotr Ilyich's inner life, thanks to the flair of inspiration was able to discern the tragic element in his mood at that time and with profound truth conveyed what I can only try to describe faintly here. Knowing my brother as I did, I can safely assert that there is no better, more truthful and staggering likeness of him as he was in life than this portrait. Yes, there are small deviations from reality in a few details of the face, but they do not obscure the main content, and I would not wish to see them corrected. It is not within the reach of man to produce something that is entirely perfect, and, God knows, perhaps the perfection of spirituality in this portrait is achieved at the expense of various insignificant inaccuracies in the individual traits of the face.}} | ||

{{quote|Kuznetsov gave this portrait as a present to Pyotr Ilyich, but the latter refused to accept it because, firstly, he did not want to have a likeness of himself at home; secondly, he did not feel entitled to give it to someone else; and, thirdly and most importantly, he did not want to deprive the artist of what he would otherwise be able to earn for this work. So instead of the portrait Pyotr Ilyich gratefully accepted as a present a delightful study of a spring landscape, which even to this day constitutes the finest adornment of the composer's rooms at the house in [[Klin]]" <ref name="note3"/>.}} | |||

The painter's daughter Mariya Kuznetsova (1880–1966) trained originally as a dancer, but went on to become a famous soprano, singing at the Mariinsky Theatre in [[Saint Petersburg]] from 1905 to 1913, after which there followed several engagements in Western Europe and North and South America. Her father painted her in the role of Mariya in Tchaikovsky's opera ''[[Mazepa]]''. | |||

==Correspondence with Tchaikovsky== | |||

One letter from Tchaikovsky to Nikolay Kuznetsov has survived, dating from 1893, and has been translated into English on this website: | |||

* '''[[Letter 4871]]''' – 20 February/4 March 1893, from [[Moscow]] | |||

One letter from Nikolay Kuznetsov to the composer, also dating from 1893, is preserved in the {{RUS-KLč}} at [[Klin]]. | |||

== | ==Bibliography== | ||

* {{bib|1903/28}} (1903) | |||

* {{bib|1940/128}} (1940) | |||

* {{bib|1946/48}} (1946) | |||

* {{bib|1956/12}} (1956) | |||

* {{bib|1969/15}} (1969) | |||

* | * {{bib|1991/48}} (1991) | ||

* | * {{bib|2007/20}} (2007) | ||

* | |||

{{ | |||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

* | * [[wikipedia:Nikolai Dmitriyevich Kuznetsov (painter)|Wikipedia]] | ||

* [http://odessaart.narod.ru/ Odessa Art website] | |||

==Notes and References== | ==Notes and References== | ||

<references> | <references> | ||

<ref name="note1">[[Letter | <ref name="note1">[[Letter 4851]] to [[Vladimir Makovsky]], 27 January/8 February 1893.</ref> | ||

<ref name="note2">[[Letter | <ref name="note2">[[Letter 4852]] to [[Modest Tchaikovsky]], 28 January/9 February 1893. The ''peredvizhniki'' (literally 'itinerants') were an important association of painters in the second half of the nineteenth century who rejected academicism in favour of travelling around Russia and seeking to capture on their canvasses scenes from the real life of the people. However, such leading painters associated with the movement as Ivan Kramskoy (1837–1887) or Ilya Repin (1844–1930) also created many fine portraits of famous contemporaries.</ref> | ||

<ref name="note3">{{bib|1997/96|Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского ; том 3}} (1997), p. 531.</ref> | |||

<ref name=" | |||

</references> | </references> | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:People|Kuznetsov, Nikolay]] | ||

[[Category:Correspondents|Kuznetsov, Nikolay]] | |||

[[Category:Painters|Kuznetsov, Nikolay]] | |||

Revision as of 09:57, 8 August 2023

Russian artist (b. 2/14 December 1850 at Stepanovka, Odessa province; d. February 1929 at Sarajevo), born Nikolay Dmitriyevich Kuznetsov (Николай Дмитриевич Кузнецов).

The son of a landowner from Kherson province, Kuznetsov was a student at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, where he was awarded three silver medals. In 1881, he began to tour widely exhibiting his works, frequently travelling abroad.

Tchaikovsky and Kuznetsov

In Odessa in January 1893 he painted the only contemporary portrait of Tchaikovsky, which now hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

A few days after leaving Odessa, Tchaikovsky wrote to Vladimir Makovsky:

I made the acquaintance of the painter N. D. Kuznetsov, who wished to paint my portrait, and this he carried out with exceptional success, as others have said and as I, too, think. Those citizens of Odessa who came to look at this portrait during the sittings expressed their extraordinary delight, amazement, and joy over the fact that such a splendid work of art was being painted in their city. The portrait was painted rather hurriedly, and that is why it may possibly not have the desired finish in the details, but in terms of its expression, lifelikeness, and authenticity it really is remarkable" [1].

Tchaikovsky also praised this portrait in a letter to his brother Modest: "In Odessa the painter Kuznetsov painted a really astonishing portrait of me. I hope that he still has enough time to send it to the peredvizhniki exhibition" [2]. In his biography of the composer, Modest said the following about Kuznetsov's portrait:

This portrait is now in the Tretyakov Gallery. The artist, who was not familiar with Pyotr Ilyich's inner life, thanks to the flair of inspiration was able to discern the tragic element in his mood at that time and with profound truth conveyed what I can only try to describe faintly here. Knowing my brother as I did, I can safely assert that there is no better, more truthful and staggering likeness of him as he was in life than this portrait. Yes, there are small deviations from reality in a few details of the face, but they do not obscure the main content, and I would not wish to see them corrected. It is not within the reach of man to produce something that is entirely perfect, and, God knows, perhaps the perfection of spirituality in this portrait is achieved at the expense of various insignificant inaccuracies in the individual traits of the face.

Kuznetsov gave this portrait as a present to Pyotr Ilyich, but the latter refused to accept it because, firstly, he did not want to have a likeness of himself at home; secondly, he did not feel entitled to give it to someone else; and, thirdly and most importantly, he did not want to deprive the artist of what he would otherwise be able to earn for this work. So instead of the portrait Pyotr Ilyich gratefully accepted as a present a delightful study of a spring landscape, which even to this day constitutes the finest adornment of the composer's rooms at the house in Klin" [3].

The painter's daughter Mariya Kuznetsova (1880–1966) trained originally as a dancer, but went on to become a famous soprano, singing at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg from 1905 to 1913, after which there followed several engagements in Western Europe and North and South America. Her father painted her in the role of Mariya in Tchaikovsky's opera Mazepa.

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

One letter from Tchaikovsky to Nikolay Kuznetsov has survived, dating from 1893, and has been translated into English on this website:

- Letter 4871 – 20 February/4 March 1893, from Moscow

One letter from Nikolay Kuznetsov to the composer, also dating from 1893, is preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin.

Bibliography

- П. И. Чайковский. К десятилетию дня кончины. Портрет работы Н. Кузнецова в Третьяковской галереей в Москве (1903)

- Портрет (1940)

- Приобретение ВОКС (1946)

- Портрет Чайковского (записано со слов М. Н. Кузнецовой-Масне) (1956)

- Портрет Чайковского (1969)

- История портрета П. И. Чайковского (1991)

- Nikolaj D. Kuznecov, der Maler des Čajkovskij-Portraits 1893, und seine Tochter, die Sängerin Marija Nikolaevna Kuznecova (2007)

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ Letter 4851 to Vladimir Makovsky, 27 January/8 February 1893.

- ↑ Letter 4852 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 28 January/9 February 1893. The peredvizhniki (literally 'itinerants') were an important association of painters in the second half of the nineteenth century who rejected academicism in favour of travelling around Russia and seeking to capture on their canvasses scenes from the real life of the people. However, such leading painters associated with the movement as Ivan Kramskoy (1837–1887) or Ilya Repin (1844–1930) also created many fine portraits of famous contemporaries.

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1997), p. 531.