Letter 807

| Date | 4/16 April 1878 |

|---|---|

| Addressed to | Sergey Taneyev |

| Where written | Clarens |

| Language | Russian |

| Autograph Location | Moscow: Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (ф. 880) |

| Publication | Письма П. И. Чайковского и С. И. Танеева (1874-1893) [1916], p. 31–33 П. И. Чайковский. С. И. Танеев. Письма (1951), p. 35–38 П. И. Чайковский. Полное собрание сочинений, том VII (1962), p. 216–219 |

Text and Translation

| Russian text (original) |

English translation By Luis Sundkvist |

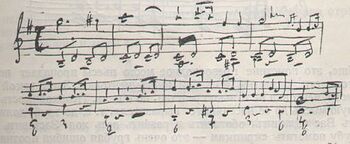

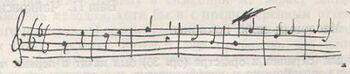

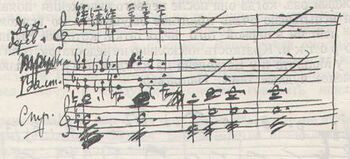

Clarens 4/16 апреля 1878 Теперь я могу без преувеличения сказать, что знаю Вашу симфонию вполне основательно. Я её много раз играл, много рассматривал партитуру и скажу Вам, что это одна из тех вещей, которые очень много выигрывают от ближайшего знакомства. На первый взгляд она не производит особенно благоприятного впечатления, быть может, оттого, что обе темы аллегро сами по себе не заключают большой прелести. Особенно это следует сказать относительно первой темы: и т. д. Вторая характернее, красивее, но всё же не первоклассного достоинства. Впрочем, спешу оговориться. В обоих этих темах нет той обаятельности, которая прельщает с первого раза. Это нисколько не значит, однакоже, чтоб они были пошлы, негодны. К ним можно присмотреться и полюбить их. Это случилось, по крайней мере, со мной. В настоящую минуту я сильно вошёл во вкус второй темы, и каждый раз, когда она после первого изложения появляется терцией выше, я испытываю очень приятное ощущение. Во всяком случае, я не вижу ни в ней, ни в первой того недостатка, который Вы находите, т. е. что они коротки. Краткость нисколько не недостаток, если мысль вполне высказана; у Моцарта и у Бетховена на каждом шагу встречаются короткие и тем не менее чудные темы. Напр[имер]: Моцарт или Бетховен и т. д. Что касается темы интродукции, хорошо мне знакомой уж давно, то и теперь, как тогда, я нахожу её превосходной и по мелодической и в особенности по гармонической красивости. Одна эта тема достаточна, чтобы служить доказательством большой талантливости её автора. Вот что я могу сказать относительно тем. Поговорю теперь о форме. В общем она весьма удовлетворительна. Это уже не ученическая работа, состоящая из кусочков, на живую нитку сшитых. В ней нет неподготовленных переходов и неестественных модуляций. В главной партии ход, непосредственно следующий за первыми осмью тактами, немножко переполнен модуляциями и вообще несколько натянут. После 8 тактов B-dur на 9-м уже оказывается cis-moll, на 11-ом D-dur, на 13-ом g-moll, на 15-ом Ges-dur, на 17-ом es-moll и т. д. Это слишком пёстро для allegro; не успеваешь уследить за всеми переходами. Возвращение к теме после этого хода, с синкопической фигурой в валторнах, очень красиво, но я сомневаюсь, чтоб эта фигура могла резко выделиться из массы оркестра. Впрочем, это недостаток инструментовки, о которой речь будет впереди. Заключение главной партии мне чрезвычайно нравится. Вся средняя часть в высшей степени интересна, хотя я не могу не заметить, что Вы повторяете себя. Она напоминает Вашу среднюю часть в первой симфонии. То же появление в каноническом порядке кусочков тем в медных инструментах, та же игра в соединение всех тем вместе, то же обилие курьёзных деталей, более красивых для зрения, чем для слуха, ибо не всегда голоса выделяются друг от друга с достаточным рельефом. Вся педаль на As перед концом превосходна, но, к сожалению, недоразвита. По-моему, необходимо было, чтоб триоли, которые у Вас в валторнах, перешли бы, наконец, в трубы и во все деревянные инструменты, а верхний голос играли бы все струнные: Вообще, это поистине превосходное место пьесы пропадает вследствие недостаточности развития и слабой инструментовки. Здесь такой случай, когда инструментовка не только средство, но и цель. Необходимость довести фанфарную мысль до её настоящего выразителя, т. е. до труб, должна была заставить Вас удлинить, обогатить и развить весь ход. Заставить в таком месте трубу помогать скрипкам—это очень грубая ошибка против инструментовки. Впрочем, я опять забегаю вперёд. Конец превосходен и чрезвычайно эффектен. Я каждый раз с любовью и восторгом останавливаюсь над этим чудным появлением темы интродукции, особенно когда трубы играют тему в B-dur. Вы сделали несомненные успехи в инструментовке, хотя это всё-таки Ваша слабая сторона. Медные играют слишком часто и много. Вступление их редко производит эффект, так как понемножку они появляются беспрестанно и назойливо суются повсюду, во все темы, во все ходы, во все имитации и контрапункты. Вообще, Ваша инструментовка недостаточно блестяща и характерна. Выделяются группы друг от друга редко. Инструментовка эта часто напоминает Шумана. Но ничего ученически неправильного в ней нет. Это скорее недостаток натуры Вашей, чем умелости. Я всегда замечал в Вас этот недостаток и нахожу, что успехи Ваши очень велики, но Вам предстоит обратить особенное внимание на него, чтобы окончательно от него освободиться. В общем же я нахожу, что Вы никоим образом не должны бросать эту первую часть. Очень немного нужно в ней доразвить и доделать, чтоб она была вполне достойна быть игранной где бы то ни было. Не смущайтесь тем, что при исполнении на репетиции она никому не понравилась. Если есть вещь, которую сразу нельзя хорошо сыграть, то это именно она. Пока всякий играющий не будет иметь ясного понятия об относительном значении каждой фразы в общем, — она не будет звучать хорошо. Для того, чтоб музыкант знал, чтó имеет первостепенное значение и чтó не должно выделяться из фона, — нужно несколько репетиций. Я бы желал знать, чтó бы сказали, если б первую часть симфонии, положим, Брамса сыграли бы только один раз на репетиции? Кому бы она понравилась? Между тем, симфония эта произвела большую сенсацию во всей Германии. Итак, Серёжа, пишите дальше и непременно доканчивайте всю симфонию. Если первая часть её и не будет феноменально-гениальным произведением, то это во всяком случае вещь очень хорошая, очень интересная и очень талантливая. Она никогда не будет особенно увлекательно действовать на слушателя, потому что она была и написана без особенно[го] увлечения. Вы её состряпали из разных старых тем, искуственно прилаженных друг к другу. Только то может увлекать, что сочинено. Вы же, по Вашему собственному выражению, придумываете. У Вас есть богатая почва для творчества, но семена ещё несколько незрелы. Это придёт само собой. А покамест достаточно и того, что есть. Ещё я хотел сделать Вам одно замечание. Вы слишком небрежно ставите штрихи смычковым инструментам. Напр[имер]: Так нельзя писать, или, по крайней мере, это очень дурно отразится на общем впечатлении. В дуэте Татьяны и Няни нужно d, а не dis. Диэз на re был поставлен нечаянно. Я еду на-днях в Россию. Партитуру Вашу Вам доставит брат Анатолий, с которым я проведу две недели у сестры и который после Святой мимоездом будет в Москве. Адрес мой отныне: Киевской губ[ерния], по Фастовской жел[езная] дор[ога], на ст[анция] Каменка. Пишите мне, голубчик. Ваш, П. Чайковский |

Clarens 4/16 April 1878 Now I can say without exaggeration that I know your symphony thoroughly [1]. I have played it lots of times, I have looked over the score a lot, and I can tell you that this is one of those pieces which gain a very great deal from closer acquaintance. At first glance it does not produce a particularly favourable impression—perhaps because both Allegro themes do not present great charm as such. This applies especially to the first theme: and so on. The second theme is more characteristic and beautiful, but all the same it is not of first-rate merit. However, I hasten to make some reservations. In both these themes there is not that charm which captivates one from the very first. This, however, does not at all mean that they are banal or useless. One can get used to them and grow fond of them. This is at least what happened to me. At present I have very much come to enjoy the second theme, and each time when, after its first exposition, it appears a third higher, I experience a very agreeable sensation. In any case, I do not see in it, nor in the first theme, that fault which you yourself find in them, that is, that they are too short. Brevity is by no means a fault, provided that the thought has been fully expressed. In Mozart and Beethoven one constantly comes across brief and yet wonderful themes. For example: Mozart or Beethoven and so on. As for the theme of the Introduction, which I have long been familiar with, I still find it now, just as I did then, superb in terms of its melodic and especially harmonic beauty. This theme alone is sufficient to serve as proof of its author's great talent. So that is what I have to say regarding the themes. Now I shall talk about the form. In general it is highly satisfactory. This is certainly no student exercise made up of hastily sewn together bits. One does not find in it any unprepared transitions and unnatural modulations. In the principal subject the progression which comes immediately after the first eight bars is somewhat overfilled with modulations and is on the whole rather strained. After 8 bars in B-flat major in the ninth you already have C-sharp minor, in the eleventh, D major, in the thirteenth, G minor, in the fifteenth, G-flat major, in the seventeenth, E-flat minor, etc. This is far too motley for an Allegro: one just can't keep up with all these transitions. The return to the theme after this progression, by means of a syncopated figure in the French horns, is very beautiful, but I doubt that this figure can stand out against the mass of the orchestra. However, this is a fault of the orchestration which I shall come to later on. The conclusion of the principal subject pleases me inordinately. The whole middle section is most interesting, though I cannot help observing that you are repeating yourself. For it resembles the middle section in your First Symphony. Here again we have the same appearance, in canonical order, of fragments of the themes in the brass instruments; the same playing at combining all the themes; the same abundance of curious details which are more beautiful for the eye than for the ear, because the voices do not always stand out from one another with sufficient distinctness. The whole pedal-point on A-flat before the end is splendid, but, unfortunately, it is developed insufficiently. In my view, it would be essential for the triplets which you have the French horns play to be finally carried over into the trumpets and all the woodwind instruments, with the upper voice being played by all the strings: Indeed, this truly superb passage in your piece is wasted as a result of the insufficient development and poor orchestration. For this is a case where the orchestration is not just a means, but a goal too. The necessity of leading the fanfare motif to its true exponent, that is to the trumpets, ought to have induced you to prolong, enrich, and develop this whole progression. Having the trumpet support the violins in such a passage is a very coarse error of orchestration. However, I am again running ahead. The ending is splendid and extremely effective. Each time I dwell lovingly and go into raptures over that wonderful appearance of the Introduction's theme, especially when the trumpets play the theme in B-flat major. You have made indisputable progress in orchestration, although this still is your weak side. You have the brass instruments play far too much and far too often. When you deploy them it rarely produces any effect, because in lesser doses they are appearing constantly and importunately thrusting themselves into all the themes, all the progressions, all the imitations and counterpoints. In general, your orchestration is insufficiently brilliant and characteristic. The instrumental groups rarely stand out from one another. Your orchestration often reminds me of Schumann [2]. However, there is nothing student-like and incorrect about it. It is rather a deficiency arising from your nature, not from lack of skill. I always noticed this deficiency in you, and it is my opinion that, though the progress you have made is certainly very great, you will have to pay particular attention to the former in order to rid yourself of it once and for all. On the whole I think that you must on no account discard this first movement. There is very little in it which you have to finish developing and polishing off in order to make it worthy of being played anywhere. Don't be discouraged by the fact that nobody liked it when it was performed at the rehearsal. If there is a piece which it is impossible to play well at once, then it is precisely this one. It will not sound well until every member of the orchestra has a clear idea of the relative importance of each phrase in general. It takes several rehearsals for a musician to know what is of first-rate importance, and what doesn't need to stand out from the background. I wonder what people would have said if the first movement, say, of Brahms's symphony had been played only once at a rehearsal. Whom could it have pleased? And yet, this symphony caused a great sensation across the whole of Germany. So, Serezha, carry on writing and finish off this symphony without fail. Even if its first movement doesn't turn out to be a phenomenal work of genius, it is in any case a very good, very interesting, and very talented piece. It will never have a particularly enthusing effect on the listener precisely because it was written without particular enthusiasm. You concocted it out of various old themes artificially joined to one another. Only that which has been composed can inspire enthusiasm. You, on the other hand, to use your own expression, are thinking up [your music]. You possess a rich soil for creative work, but the seeds are still somewhat unripe. That, however, will come of itself. For the time being it is enough with what we have. There is one more criticism I would like to make. You are far too careless when indicating the bow strokes for the string instruments. For example: One cannot write like that, or, at least, it has a very bad effect on the overall impression. In the duet between Tatyana and the Nurse it needs to be D, not D-sharp [3]. The sharp before D was put there by mistake. I shall be leaving for Russia any day now. Your score will be delivered to you by my brother Anatoly, with whom I shall spend two weeks with my sister, and who will pass through Moscow after Holy Week. My address is henceforth: Kiev Province, on the Fastov Railway, at Kamenka station. Write to me, golubchik. Yours, P. Tchaikovsky |

Notes and References

- ↑ Taneyev had sent his former teacher the score of the first movement of his Symphony No. 2 in B-flat minor, which he was working on at the time, but which ultimately remained unfinished.

- ↑ One of the criticisms which Tchaikovsky consistently made of Schumann's symphonies, notwithstanding all the admiration which he felt for them, was what he considered to be their grey orchestration, and according to his friend Ivan Klimenko he more than once considered re-orchestrating all four of the German master's symphonies.

- ↑ Taneyev was checking the piano reduction which Tchaikovsky had made of Yevgeny Onegin against the full score, and in his letter to Tchaikovsky of 18/30 March–22 March/3 April 1878 he had pointed out that in one syllable of the above phrase («Ах, няня, няня, до того ли?» / "Oh, Nanny, what does it matter?"), as written in the full score, Tatyana appeared to sing a D-sharp whereas the violins echoing her played D natural. See Taneyev's letter in П. И. Чайковский. С. И. Танеев. Письма (1951), p. 33.