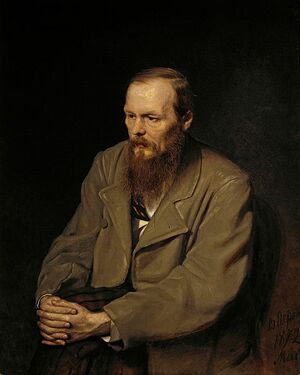

Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Russian novelist (b. 30 October/11 November 1821 in Moscow; d. 28 January/9 February 1881 in Saint Petersburg), born Fyodor Mikhaylovich Dostoyevsky (Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский).

Biography

One of the greatest Russian writers of the nineteenth century, Dostoyevsky was born into the family of a hospital doctor in Moscow. His mother died of tuberculosis in 1837 and his father was murdered by his serfs in 1839 — these tragic losses, as well as the many trials and tribulations of later years, would test his Christian faith severely, and one of the main themes of his writing became the search for divine and human goodness in a world so full of selfishness and wanton acts of evil. At the age of 17, Dostoyevsky was sent to the Military Engineering Academy in Saint Petersburg, but in the five years he spent there (1838–43) he was far more interested in reading such favourite authors as Pushkin, Schiller, Shakespeare, and Balzac, as well as in making his first literary attempts, than in his fortification studies. After graduating he worked briefly as a draughtsman in the Engineering Corps, but soon resigned his commission to devote himself entirely to writing. His first novel Poor Folk (1845) was hailed by Russia's leading critic Vissarion Belinsky (1811–1848) as the most important contribution to Russian literature since Gogol, but subsequent works (among them several fine stories) were less favourably received by Belinsky. In 1846, Dostoyevsky also became a member of the Petrashevsky Circle in Saint Petersburg, which would gather regularly to discuss the latest ideas in Western philosophy and social thought. Musicians such as Anton Rubinstein would sometimes also take part in these gatherings, and on one occasion early in 1849 Glinka performed his song To Her (К ней) at a soirée of the circle — an unforgettable experience for Dostoyevsky, which he would later refer to in one of his stories [1]. When the government of Tsar Nicholas I, in April 1849, decided to clamp down on any such liberal discussion groups, Dostoyevsky was arrested along with other members of the circle and sentenced to death by firing squad. At the very last moment the Tsar's pardon was read out to the condemned prisoners and Dostoyevsky's sentence commuted to 4 years of hard labour in Siberia followed by 4 years of military service.

Both the traumatic experience of this mock execution and the years spent in Siberia among convicts drawn mainly from the common folk would have a decisive influence on Dostoyevsky's later writing. The harsh conditions of Siberia also aggravated his congenital epilepsy, leading to seizures which would haunt him all his life. In December 1859, Dostoyevsky was finally allowed to return to Saint Petersburg by Tsar Alexander II. The following years were marked by a flurry of journalistic and literary work, some of which was carried out during long stays in Europe (where he would escape from his many creditors in Russia). While still in exile, he had married in 1857 Mariya Dmitriyevna Isayeva (1824–1864), a widow with a son whom he adopted. In 1867, Dostoyevsky married his second wife, Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina (1846–1918), who was to be his most loyal support in the remaining years of his life. She bore him four children, but only two survived infancy. In the years after his return from Siberia, Dostoyevsky, in spite of all adversity, produced some of the most profound and gripping works of world literature, amongst them his famous novels: Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1868–69), The Devils (1871–72), and The Brothers Karamazov (1878–80).

Tchaikovsky and Dostoyevsky

In an excellent monograph on the topic of "Dostoyevsky and music", the Soviet musicologist Abram Gozenpud (1908–2004) has explored the frequent recurrence of musical themes in Dostoyevsky's writings, as well as making illuminating parallels between the latter and the works of several composers — both contemporaries of the great novelist (Tchaikovsky and Musorgsky) and those belonging to later generations (notably Janáček, Mahler, Stravinsky, and Shostakovich). Although it cannot be established with complete certainty whether Tchaikovsky really met Dostoyevsky in 1864 — as implied by the memoirs of Herman Laroche, written more than thirty years later — the paths of these two unique artists did cross in some very interesting ways, as we shall see.

First of all, it is worth noting that, despite not having any formal musical background, Dostoyevsky's love of music was genuine and lasted all his life. Many of his strongest musical impressions, however, occurred in his youth: a recital given by Liszt in Saint Petersburg in 1843; the three concerts conducted there by Berlioz in 1847, featuring in particular the dramatic symphony Roméo et Juliette; and the famous seasons of the Italian Opera Company at the Mariinsky Theatre (1843–46), starring such renowned singers as Pauline Viardot, whose interpretation of Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia influenced the story White Nights (1848). According to contemporary accounts, Dostoyevsky even in later years was very fond of humming arias from Italian operas. In 1843, he also attended a performance of Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila, which became his favourite opera: he would later try to instil in his children a love for this work [2]. However, another of Dostoyevsky's favourite composers was Beethoven, and this may shed some light on why, in 1873, Tchaikovsky started writing an article on the German composer (TH 275) for a newspaper which was then being edited by Dostoyevsky (more on this below). From the memoirs of the famous Russian mathematician Sofya Kovalevskaya (1850–1891), whose family Dostoyevsky frequently called on in the winter of 1864–65 because he was infatuated with Sofya's elder sister, we find out that he liked Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique more than anything else! [3] The writer's second wife Anna Grigoryevna also recalled how during their long stays in Dresden between 1867 and 1871 Dostoyevsky enthusiastically attended the free public concerts in the municipal park where he could frequently hear music by Beethoven. He liked Fidelio especially, and, after hearing the overture to the opera on one occasion, he exclaimed: "In Beethoven there's always passion and love. He is a poet of love, happiness, and of the pangs of love!" [4] Tchaikovsky's attitude to Beethoven was rather more complicated, but the fact that he often described the latter's works as expressing the tragic defeat by Fate of human yearnings for happiness (see e.g. TH 301) shows that he, too, responded to those elements in Beethoven's music which Dostoyevsky was so enthusiastic about.

Shortly after his return from Siberia, Dostoyevsky had founded, in 1860, a journal with his elder brother Mikhail which was called Time (Время). In this new periodical, as well as in its successor Epoch (Эпоха) — which the Dostoyevsky brothers set up early in 1864 after Time was banned by the government for daring to discuss political matters — the composer and critic Aleksandr Serov published several of his articles during the first half of the 1860s. Dostoyevsky got on well with Serov and liked his second opera Rogneda (1865), which was set in pagan Kiev on the eve of Russia's conversion to Christianity and which reflected to some extent the 'return to the soil' (почвенничество) ideals that he himself had espoused at the time [5]. According to the memoirs of Herman Laroche, when Tchaikovsky finally agreed to go to one of the soirées at Serov's flat in the autumn of 1864, Dostoyevsky also happened to be present. Laroche observed in this regard: "I remember that on that occasion Fyodor Dostoyevsky was among the guests, and that he talked a lot about music, though quite senselessly, just like a true man of letters who hasn't had any musical education and who doesn't have a musical ear anyway" [6]. Unfortunately, neither Dostoyevsky nor Tchaikovsky in later years referred to such a meeting at Serov's flat, so Laroche's account cannot be corroborated.

Abram Gozenpud points out that the above disparaging remarks about Dostoyevsky's lack of competence to judge in musical matters reflect Laroche's hostile attitude towards the writer. Thus, Laroche would argue in an article of 1876 that Dostoyevsky had become a reactionary who defended the value of suffering for its own sake, as a purifying force, and who had thereby betrayed the cause of fighting social injustice that he had rallied to in his youth. In 1882, a year after Dostoyevsky's death, Laroche wrote ironically that future generations could acquaint themselves with the "belles-lettres of reaction" by reading Dostoyevsky's works and that "the average reader of the future will probably be astonished by their far-fetched plots, the morbid tension built up in them, the lack of simplicity […] Such a reader will not be able to understand very much in this never-ending 'dance of death'" [7]. Now Tchaikovsky for his part was no 'fan' of Dostoyevsky, as the letter extracts compiled below clearly indicate, but unlike his friend Laroche, he did recognize Dostoyevsky to be "a writer of genius", albeit one who was "antipathetic" to him (see letter 1838 to his brother Modest below).

It is difficult to speculate on what Dostoyevsky and Tchaikovsky might have talked about had they met on that occasion in 1864. After all, one was already a prominent writer, the author of Notes from the House of the Dead (1862) whose compassionate yet truthful description of life on the penal colony in Siberia had caused a sensation; the other was still a student whose great gifts were unknown to anyone except for a handful of friends and teachers at the Conservatory. Besides, Dostoyevsky at that time seems to have had a very low opinion of Nikolay Rubinstein, and if he expressed this openly in the course of that soirée, it is likely that Tchaikovsky would have kept his indignation to himself and not allowed himself to be drawn into an argument — just as he avoided quarrelling with Serov, even when the latter furiously attacked the Rubinstein brothers. By 1872, though, Dostoyevsky's attitude to Nikolay Rubinstein had changed, and from a letter he wrote in that year to his niece, who had studied the piano at the Moscow Conservatory, it is clear that he now respected Rubinstein and appreciated what he had done to promote musical education in Russia [8]. In 1880, Nikolay Rubinstein would direct the musical section of the festivities to mark the unveiling of the Pushkin monument in Moscow — an event which, thanks to Dostoyevsky's famous speech on that occasion, would have direct consequences for the fate of Tchaikovsky's opera Yevgeny Onegin, as will soon become clear.

During February and March 1873, the Saint Petersburg weekly newspaper The Citizen (Гражданин) published four instalments of a series of articles by Tchaikovsky entitled Beethoven and His Time. The editor of this newspaper at the time was none other than Dostoyevsky, who held this post from January 1873 to April 1874. Unfortunately, it has not been possible to clarify the circumstances which led to this job being commissioned from Tchaikovsky, who until then had written music review articles exclusively for journals in Moscow, where he was himself still based. Tchaikovsky may have been offered this assignment by the newspaper's owner, Prince Vladimir Meshchersky (1839–1914), who was an old classmate of his at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence. This would certainly be in keeping with Meshchersky's policy of trying to enlist well-known contributors for his new publication (only founded in 1872), knowing that many readers would otherwise shun The Citizen because of its reactionary credentials. Dostoyevsky himself had been offered the editorship of The Citizen precisely with that aim in mind, and Tchaikovsky, then a rising young composer, would evidently also have been a welcome addition to the newspaper's roster of collaborators. What is not clear is whether the idea for this mini-biography of Beethoven was Tchaikovsky's own, or whether it came from Meshchersky or Dostoyevsky, a fervent admirer of Beethoven's music as we have seen. A. Gozenpud does, however, point out that such an article could not have been published without the consent of Dostoyevsky in his capacity as editor of The Citizen. Tchaikovsky did not actually complete Beethoven and His Time — perhaps because he grew tired of a task that required little original input (for these articles were in fact largely based on Alexander Wheelock Thayer's famous biography of the German composer). In later issues of The Citizen, unfortunately, no explanation was given by the editor as to why Tchaikovsky's series of articles had been discontinued.

Neither has it been possible to ascertain whether Tchaikovsky went to see Dostoyevsky during his brief visit to Saint Petersburg at the end of 1872 (26–27 December [N.S.]) to discuss his forthcoming contribution to The Citizen with the newly designated editor. Indeed, Tchaikovsky's name is not mentioned at all in Dostoyevsky's writings (including his correspondence), and it does seem as if the latter never had an opportunity to hear any of his younger contemporary's music. Still, they both had a number of mutual friends in the 1870s: the contralto Yelizaveta Lavrovskaya, whom Dostoyevsky was very fond of, the baritones Ivan Melnikov and Ippolit Pryanishnikov, and the young soprano Mariya Klimentova, the first performer on the stage of Tatyana in Tchaikovsky's opera [9].

By a strange coincidence, it so happened that just as Tchaikovsky was reading the first instalments of The Brothers Karamazov, which began to be serialized in January 1879, the children of his sister Aleksandra fell ill with measles. Tchaikovsky's alarm when he heard about this (he was then staying in France) was compounded by his reading of Dostoyevsky's novel in which the unjustified suffering of children plays such an important role both in the plot and in the philosophical argument between Ivan Karamazov and his brother Alesha. The letters in which Tchaikovsky made tormenting parallels between the pain which he imagined his little nephews Vladimir and Yury would be going through, and one of the scenes in the novel are quoted in the list below: from these one can see clearly why Tchaikovsky recognized Dostoyevsky's "genius", even if his books did not appeal to him [10].

When Nadezhda von Meck found out that Tchaikovsky was reading such an 'unpleasant' author, she wrote to him: "Why, my friend, are you reading Dostoyevsky? Your nerves won't be able to take it! After his Crime and Punishment I swore that I would never read one more work of his, and I certainly have kept my word. He is a remarkable psychologist and chooses for his works the most painful states of mind and heart in order to show off his astonishing gift of psychological analysis and art of exposition. He is not made for people like you and me" [11]. Tchaikovsky did not heed the well-meant advice of his benefactress because later that year, while staying in her cottage at Simaki, he asked her to send him some more books: specifically, the complete works of Tolstoy, his favourite writer, and Dostoyevsky! [12] From letters to his brother Modest quoted below, we also know that he did finish The Brothers Karamazov, despite the fact that he found it to be such heavy reading.

Dostoyevsky and "Onegin"

Although interesting parallels have been made between the portrayal of Herman in The Queen of Spades and such heroes of Dostoyevsky's as Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment or Aleksey Ivanovich in The Gambler (who are both in their turn descended from Herman in Pushkin's original short story); or between Mariya's madness at the end of Mazepa and Prince Myshkin's final breakdown at the end of The Idiot, the most profitable way in which Tchaikovsky and Dostoyevsky can be compared has to do with their responses to Pushkin's novel in verse Yevgeny Onegin (1825–32).

Despite being the younger of the two, Tchaikovsky was the first to present his 'interpretation' of Pushkin's novel to the Russian public, with his opera Yevgeny Onegin (1879). Both musically and in terms of dramatic tension the central figure of Tchaikovsky's opera is clearly not Onegin but Tatyana. That this young woman should awaken such admiration, however, was not at all that obvious, for the great critic Belinsky, in two influential articles he wrote about Pushkin's novel in 1844–45, had argued that Tatyana, no matter how touching her passionate and sincere nature might be, was far less interesting a character than Onegin, with all his world-weariness. Moreover, Belinsky claimed that Tatyana at the end of the novel had become a slave of social convention, and that nothing but fear for her reputation prevented her from eloping with Onegin, whom she still loved! In his articles, Belinsky frequently tacked onto a literary character or situation a whole philippic against the ills of Russian society, and it was the same with his discussion of Pushkin's novel. Thus, Tatyana's parting words to Onegin: "I love you (why hide it?), / But I have been given in marriage to another; / I shall be faithful to him all my life" [Я вас люблю (к чему лукавить), / Но я другому отдана; / Я буду век ему верна] provoked the critic's indignation at how in Russia young girls were so often forced by their parents to marry against their inclination and how they were then expected to be faithful to unloved husbands, or at least to keep up the appearance of doing so.

Tchaikovsky's understanding of Tatyana's conduct at the end of Pushkin's novel was quite different: both in the musical structure of her final duet with Onegin in the opera and in the libretto he emphasized her spiritual fortitude [13]. At the same time, though, Tchaikovsky felt that "for the sake of musical and theatrical demands" he had to "strongly dramatize" her encounter with Onegin, which in Pushkin's novel is described with such sobriety [14]. To highlight the beauty of her character, Tchaikovsky realised that it was necessary to show just how much pain and sacrifice it cost her to achieve this victory over her true feelings. Thus, the libretto and stage directions for the final scene deviate considerably from Pushkin's original text: Tchaikovsky has Tatyana confess that she still loves Onegin not at the very end, just before she leaves the room, as in Pushkin, but quite early on; and, more significantly, overwhelmed by her confession, she actually falls into his arms, and, although she immediately frees herself from his embrace, a few moments later she sinks onto his breast yet again before finally rushing out of the room. In a further deviation from the novel, Tatyana's husband was to appear at the door and with an imperious gesture order Onegin to leave his house. Tchaikovsky did not feel that these stage directions traduced the spirit of Pushkin's novel [15], and this is in fact how the final scene was presented in the first edition of the piano score of Yevgeny Onegin (October 1878).

At the premiere of the opera in the Maly Theatre in Moscow on 17/29 March 1879, with students from the Conservatory and notably Mariya Klimentova in the role of Tatyana, this finale, in particular, awakened strong misgivings amongst those who knew Pushkin's novel by heart. Thus, Laroche, in his review of the opera, before praising enthusiastically the melodic richness of Tchaikovsky's music, took the libretto to pieces and pointed out ironically how the composer "with these five minutes of kisses and embraces had effectively made Tatyana refute her famous declaration: 'I have been given in marriage to another; / I shall be faithful to him all my life'" [16]. Tchaikovsky, however, did not make any alterations to the final scene at this time.

It was in the following year, in June 1880, that Dostoyevsky presented himself before the Russian public with his own compelling interpretation of Pushkin's novel. The occasion was the unveiling of a monument to Russia's greatest poet in Moscow. The festivities, which Tchaikovsky did not attend (he was then staying in Kamenka), began on 5/17 June with a solemn prayer service. On 6/18 June, the monument was unveiled and a literary-musical soirée was held in the evening at which Dostoyevsky and his old rival Ivan Turgenev, the most prominent guests, read extracts from Pushkin's works. In the musical part of the proceedings Nikolay Rubinstein conducted a small orchestra in performances of the overtures to Glinka's Ruslan and Lyudmila and Dargomyzhsky's Rusalka, as well as the Letter Scene from Tchaikovsky's Yevgeny Onegin, with Mariya Klimentova again singing Tatyana. As far as we can tell, this was the first time that Dostoyevsky had a chance to hear Tchaikovsky's music (whereas Turgenev, for example, had been familiar with the whole opera for well over a year). On 7/19 June, Turgenev delivered his speech on Pushkin, which was full of subtle insights about his beloved poet's artistry, as well as comparisons with the national poets of other countries (Shakespeare, Goethe, Molière etc): highly nuanced and objective as this lecture was, it did not awaken much enthusiasm. In contrast, Dostoyevsky's speech the following day, on 8/20 June 1880, caused a sensation. With the most impassioned arguments Dostoyevsky demonstrated that Pushkin, above all in his verse-novel Yevgeny Onegin, had anticipated the spiritual crisis of contemporary Russia — an intelligentsia estranged from its native soil by the Western education and ideas it had soaked up — and at the same time also showed the way out of this crisis by pointing to the finest qualities of the Russian national character in such figures as Tatyana — "the apotheosis of Russian womanhood", as he described her. Challenging the interpretation which Belinsky had made forty years earlier, Dostoyevsky argued that Tatyana did not elope with Onegin at the end of the novel not because she was afraid of what society would say, but because she could see through Onegin's lack of faith and, most importantly, because as a true Russian woman, she could not selfishly base her happiness on the sufferings of another:

Tell me, could Tatyana have decided otherwise, what with her lofty soul, with her heart that had suffered so much? No, this is how a pure Russian soul thinks: even if I must forfeit my happiness; even if my unhappiness is immeasurably greater than the misfortune which that old man would suffer; even if no one, including the old general, ever finds out about my sacrifice and appreciates it, I do not wish to become happy by ruining another!'" [17]

Dostoyevsky's speech, which ended with an invocation of Russia's historical mission to show the whole world how universal brotherhood could be achieved in the spirit of Christian love, was received with a frenzy of applause which lasted a whole half-hour. Many in the audience cried and wept, one student fainted, and Turgenev even rushed up to his old enemy with tears in his eyes and embraced him. It was perhaps the happiest day in Dostoyevsky's life, otherwise so full of misfortunes.

Rolf-Dieter Kluge has rightly observed that both Tchaikovsky and Dostoyevsky focussed on Tatyana in their reading of Yevgeny Onegin, and, just as Dostoyevsky insisted in his speech that Pushkin ought to have named his novel after Tatyana, since she was its true heroine, so the same might be said about Tchaikovsky's opera! [18] Nevertheless, there was one important difference in their approach to Tatyana: according to Dostoyevsky, it could never so much as have crossed her mind to run away with Onegin, since she was incapable of hurting her "old husband" (an important phrase in Dostoyevsky's speech, as we shall see). Tchaikovsky, in contrast, intended Tatyana to swoon in Onegin's arms, and, in the original version of the final scene, her husband was actually to appear at the end: "Prince Gremin enters. Tatyana, having seen him, lets out a cry, and falls into his embrace unconscious. The prince makes an authoritative gesture to Onegin to leave" [19]. Thus, Tchaikovsky, by seeking to emphasize the suffering which the fulfilment of duty entailed for Tatyana, had still conceded the strength of her love for Onegin: this to some extent seemed to confirm Belinsky's interpretation of her behaving, if not hypocritically, then certainly with a denial of her true feelings for the sake of some abstract concept of duty! Mariya Klimentova, the first performer of Tatyana in Tchaikovsky's opera, was at first confused as to how such bitter self-abnegation could be reconciled with Tatyana's earlier passionate sincerity. As Abram Gozenpud has convincingly argued, it was Dostoyevsky's speech in 1880 that helped her to appreciate her heroine's conduct in the crucial final scene of the opera [20].

For although Tchaikovsky himself was not among the audience who heard Dostoyevsky deliver his inspired address, Klimentova and a few other people close to Tchaikovsky were there on that memorable day: Nikolay Rubinstein, Sergey Taneyev [21], and the composer's brother Anatoly. Klimentova, who was due to appear as Tatyana again in the first professional staging of Yevgeny Onegin at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow early in 1881, wrote to Dostoyevsky shortly after the conclusion of the Pushkin festivities, saying that she hoped to be able to make use of what she had learnt from his speech: "Tatyana more than ever before stands now before my eyes like a living person and urges me on to portray her as truthfully as possible" [22]. Dostoyevsky's enthusiastic praise of Tatyana's moral integrity provided Klimentova with the key to understand why it was in keeping with her altruistic character to reject Onegin's entreaties to elope with him.

Dostoyevsky did not ultimately have the opportunity to see a performance of Tchaikovsky's whole opera (as noted above, he just heard Klimentova in the Letter Scene on 6/18 June 1880), but the composer's brother Anatoly was clearly worried at what Dostoyevsky and indeed everyone who had heard or read his speech on Pushkin (it was published in various newspapers and journals) might say if the following year, when Yevgeny Onegin was to be staged at the Bolshoi Theatre, they suddenly saw Tatyana apparently waver in her resolve and fall into Onegin's arms! Thus, Anatoly urged his brother to make some changes to the final scene, bringing it into line with Pushkin's more sober conclusion. In his reply to Anatoly on 17/29 October 1880 (letter 1614), Tchaikovsky reluctantly agreed to amend the stage directions for that scene: now Onegin was not to touch Tatyana at all, and instead of her husband ominously entering, she was to leave the room saying "Farewell for ever!" [Прощай навеки!] to Onegin. At the end of this letter (which is quoted in more detail in the work history for Yevgeny Onegin), Tchaikovsky asked Anatoly to show these changes to several people who were involved in the preparations for the staging of his opera at the Bolshoi Theatre: Klimentova, the director of the Imperial Theatres Vladimir Begichev, the conductor Enrico Bevignani, and Nikolay Rubinstein, who had been actively involved with the opera ever since its first performances by Conservatory students. Anatoly replied to the composer a few days later:

I am awfully happy that you agreed to these alterations. For truly!, almost every time that Onegin is mentioned, people immediately start talking about how you were so wrong to try to improve on Pushkin. All this has been caused by Dostoyevsky's speech and the August issue of his Diary of a Writer" [23].

However, not all of the changes agreed to by Tchaikovsky in deference to Dostoyevsky's compelling interpretation of Tatyana were actually implemented in the theatre. For in subsequent editions of the score and performances of the opera (even during the composer's lifetime), the stage directions continued to have Tatyana struggling to free herself from Onegin's embraces, as Tchaikovsky had intended from the very start. One crucial amendment, though, was made in accordance with Tchaikovsky's decision as stated in that letter to his brother: Tatyana's husband, Prince Gremin, was no longer to appear in the final scene.

As Abram Gozenpud has pointed out, Dostoyevsky's Pushkin speech also had another more tangible effect on Tchaikovsky's opera, specifically on the characterization of Prince Gremin. In Pushkin's novel, Tatyana's husband is unnamed (he is referred to merely as the prince) and plays a very minor role in the ball scene — there is certainly nothing comparable to Gremin's beautiful aria in the opera [24]. Moreover, it is clear that Tatyana's husband in the novel is only a few years older than Onegin (who is 26 when he appears at the ball), since at one point they share reminiscences of pranks which they had got up to together when they were younger. The fact that the prince is also described as a general in the novel does not contradict this and implies that he must be at least middle-aged because historical records show that in 1825 (the year in which the novel's final chapter is set), several noblemen who had fought as teenagers in the Russian campaign against Napoleon (1812–15) had already been promoted to the rank of general! Now, it is very interesting that Dostoyevsky in his speech repeatedly referred to Tatyana's husband as "the old general" (старик-генерал). Whether in this respect Dostoyevsky was carried away by his imagination, or whether he was identifying himself to some extent with this fictional figure (since he was himself considerably older than his wife Anna), is a matter for speculation. The point, though, is that, to quote A. Gozenpud:

Dostoyevsky in his speech called Tatyana's husband an old man, evidently in order to emphasize the heroine's selflessness. And yet the general is Onegin's friend and is of the same age as he is. The magic of Dostoyevsky's speech, however, was such that, starting from the production of Yevgeny Onegin at the Bolshoi Theatre in 1881, Gremin has always turned out to be middle-aged, and sometimes even elderly. This tradition has endured right up to our own times" [25].

Postlude

After Dostoyevsky's death we know that Tchaikovsky continued to read his works (e.g. his early novel The Double, as recorded in a diary entry of 1889 which is quoted below), and when he visited Paris in the summer of 1886 he bought copies of recently published French editions of Crime and Punishment and Notes from the Underground, expressing his delight in a letter to Nadezhda von Meck (also quoted below) that the best Russian authors were now being appreciated in France, as well as the hope that the same fate would soon befall Russian music! Nevertheless, it must be emphasized again that Tchaikovsky professed little affection for Dostoyevsky — at any rate far less than what he felt for Tolstoy, even when the latter had forsaken fiction and started writing tracts on moral, religious, and social problems. This is reflected, for example, in the way Tchaikovsky recorded in his diary his impressions of What I Believe (В чём моя вера) (1884) — one of the books which Tolstoy wrote after his 'conversion' — but left no note of his thoughts on Dostoyevsky's The Double, which he was reading at the same time, in Frolovskoye in early 1889 [26]. Two very important letters — letter 3210 to Yuliya Shpazhinskaya of 26 March/7 April 1887 and letter 3966 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich of 29 October/10 November 1889 (letter 3966) — suggest why Tchaikovsky preferred Tolstoy so much: in contrast to Dostoyevsky (and Dickens), there were no villains in Tolstoy's works. Rather, all characters were equally dear to him in all their human weakness and helplessness, and he pitied them all without exception, not just "the insulted and injured", whom Dostoyevsky so often concentrated on [27]. (For more details, see the entry on Tolstoy.)

General Reflections on Dostoyevsky

In Tchaikovsky's Letters

- Letter 2955 to Nadezhda von Meck, 19/31 May 1886, from Paris:

How nice it is to be able to verify with one's own eyes the success of our country's literature in France. All the shop-windows here flaunt translations of Tolstoy, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, Pisemsky, and Goncharov. In the newspapers one constantly comes across enthusiastic articles about one or the other of these writers. Maybe such a time will also come for Russian music!

- Letter 3093 to Yuliya Shpazhinskaya, 10/22 November 1886, in which Tchaikovsky encourages her to write, not only as a way of overcoming her sufferings (she had recently become estranged from her husband Ippolit Shpazhinsky), but because he was genuinely convinced of her literary talent:

You were born to be a writer, an artist, and I simply cannot understand why you did not embark on your real vocation earlier, when this breakdown hadn't yet taken place. But even such a spiritual breakdown [надломленность] is not an obstacle. On the contrary, it can infuse your writing with that morbid note on which the tremendous success of Dostoyevsky, say, is founded

In Tchaikovsky's Diaries

- Diary entries for 31 July/12 August and 1/13 August 1886, Maydanovo:

July 31. […] While reading the article by Voguë (Le roman Russe) about Turgenev, I cried. Went for a walk […] After dinner I read Bourget (about Turgenev, Amiel and the Goncourt brothers etc) […].

August 1. […] Read Voguë on Dostoyevsky and cried again" [28]

On Specific Works by Dostoyevsky

In Tchaikovsky's Letters

- The Brothers Karamazov (1878–80)

- Letter 1110 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 15/27 February 1879, from Paris, in which Tchaikovsky says how worried he was by the news that some of their sister Aleksandra's children had caught the measles:

…Sasha thinks they will all fall ill. This alarmed me so much that I immediately sent a telegram and paid in advance for the reply, to find out what the children's state of health is. Yury has the measles!! I mean, it's impossible to think about that without crying. And it so happens that I'm under the impression of Dostoyevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov. If you haven't read this, rush off immediately and get yourself a copy of the January issue of the Russian Messenger. There's one scene where the elderly monk Zosima is receiving visitors on the grounds of the monastery. Amongst these there's a woman who is crushed with grief because all her children have died, and after the death of the youngest she was overcome by a mad anguish that caused her to leave her husband and go off wandering around the countryside. When I read her account of the death of her last child and the words in which she describes her irreparable grief, I burst into tears — I hadn't cried like that over a book for a very long time. This has produced a staggering impression on me [29]

- Letter 1111 to Nadezhda von Meck, 16/28 February–17 February/1 March 1879, in which Tchaikovsky also mentions the alarming news from his sister Aleksandra Davydova:

The thought that all the children are ill, that their merry little house has turned into a sinister hospital, upset me greatly, and I hastened to send a telegram, asking for a quick reply, but nothing has arrived yet. I know that there's nothing dangerous about measles, but it's just so unbearably painful for me to think that my pet Volodya and little Yury are lying there in fever and suffering. Besides, for two days now I have been under a strong impression from Dostoyevsky's novel The Brothers Karamazov. Two days ago in the evening I read the first chapters of this tale in your issue of the Russian Messenger. In it, as is always the case with Dostoyevsky, there feature prominently various strange madcaps, various morbidly nervous characters who remind one more of beings from the realm of febrile delirium and nightmare, than of real people. As is always the case with him, in this tale, too, there is something painful, depressing, and forlorn, but, as always, there are also the occasional episodes almost of genius — unfathomable revelations of artistic analysis. There is one scene there which affected and shook me so powerfully that I burst into tears and had a fit of hysterics: it is where the elderly monk Zosima receives various sufferers who have come to him hoping to be healed. Amongst them is a woman who has walked over 300 miles to seek consolation from him. All her children had died one by one. After burying the youngest she had lost the strength to struggle against her grief, so she left her house and husband and started wandering through the countryside. The simplicity with which she describes her irreparable despair, the staggering force of the simple words which convey her endless grief at the fact that she will never, never, never see and hear that child again, and especially when she says: I wouldn't even go up to him, I wouldn't say a word; I'd just hide myself in a corner if only I could just look at him for a few seconds — all this tugged so painfully at my heartstrings and still does. Yes, my friend! It is better to have to die oneself every day for a thousand years than to lose those whom one loves and to seek consolation in the hypothetical idea that we shall meet again in the other world! Will we meet again? Happy are those who manage not to have doubts about this

- Letter 1186 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 20 May/1 June 1879:

In the latest issue of the Russian Messenger I've read the next instalments of The Karamazovs. This is beginning to become unbearable. All the characters without exception are crazy. That's how it always is: one can put up with Dostoyevsky only during the first part of his novels. What comes afterwards is sheer chaos.

- Letter 1838 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 23 August/4 September 1881:

I am reading The Karamazovs and am yearning to finish it soon. Dostoyevsky is a writer of genius, but an antipathetic one. The more I read, the more he weighs down on me [30]

External Links

Bibliography

- Gozenpud, A. Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (Достоевский и музыкально-театральное искусство) (Leningrad, 1981)

- English text of Dostoyevsky's speech on Pushkin, 8/20 June 1880 (translated by S. Koteliansky and J. Middleton Murry for a 1916 American edition of Diary of a Writer), available Pushkinspeech.html online

- Vaidman, P. Entry on Dostoyevsky for the Belcanto Tchaikovsky Pages (in Russian)

Notes and References

- ↑ Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 70. The story in question is The Eternal Husband (1869), where one of the main characters, Vel'chaninov, reminisces on Glinka's inspired performance of that song. From other contemporary accounts of this soirée, we also know that, apart from this romance, Glinka performed some arias from Ruslan and Lyudmila, the Kamarinskaya, and a few pieces by Gluck and Chopin (see: Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 70).

- ↑ Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 19–20.

- ↑ A. S. Dolinin (ed.), Достоевский в воспоминаниях современников, 2 vols (1964), vol.1, p. 358.

- ↑ Letter from Fyodor Dostoyevsky to his wife Anna, 18/30 July 1875, from Bad Ems. Quoted in: Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 116.

- ↑ Such ideals as submission to the will of God, for example, and the rejection of individual wilfulness. This issue is discussed in Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 91–92, and at greater length in: Richard Taruskin, Opera and Drama in Russia — As Preached and Practiced in the 1860s (Rochester, NY, 1993), Chapter 3: "Pochvennichestvo on the Russian operatic stage: Serov and his Rogneda". The 'pochvennichestvo' movement (whose name is derived from the Russian word 'почва' ('soil') argued that the educated classes in Russia had to stop being in thrall to Western European ideas and return to the native soil, that is by appreciating the traditions and beliefs of the Russian peasantry.

- ↑ Herman Laroche, П. И. Чайковский в Петербургской консерваторий [P. I. Tchaikovsky at the Petersburg Conservatory] in Воспоминания о П. И. Чайковском (1980), p. 59.

- ↑ These quotations from articles by Herman Laroche are given in: Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 158–159.

- ↑ This letter is quoted in: Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 91.

- ↑ See also Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), Chapter IX. Mariya Klimentova sang Tatyana at the premiere of Yevgeny Onegin as performed by students of the Moscow Conservatory at the Maly Theatre in Moscow on 17/29 March 1879; but a few days earlier, on 6/18 March 1879, in the salon of the amateur singer Yuliya Abaza in Saint Petersburg, a private performance of the opera sung from the vocal-piano reduction had taken place, in which Aleksandra Panayeva had taken the role of Tatyana. The accompanist at the piano was apparently Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich. See letter 1058 to Nadezhda von Meck, 5/17 January 1879.

- ↑ Incidentally, it is also by reference to The Brothers Karamazov that Abram Gozenpud (Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 169–172) rightly stresses the affinity between Dostoyevsky and Musorgsky, especially in the opera Boris Godunov, where Tsar Boris, a loving father to his own children, is haunted by his guilt over the murder of the infant Dmitry. Dostoyevsky and Musorgsky are known to have met at least once, at a literary-musical soirée in Saint Petersburg on 5/17 April 1879, and although Dostoyevsky does not seem to have taken any notice of the latter's music, and, vice versa, Dostoyevsky is hardly mentioned at all in Musorgsky's letters, there is no doubt about the essential affinity between these two great Russian artists. Gozenpud also notes how at a soirée organized on 3/15 February 1881, in memory of the late Dostoyevsky, Musorgsky (who just had a few more weeks to live himself) sat down at the piano and improvised a funerary lament like that with which the opera Boris Godunov concludes. In view of this resemblance, it does not seem to be a coincidence that Tchaikovsky was repelled by both of them, although at the same time he sensed something of their unique power!.

- ↑ Letter from Nadezhda von Meck to Tchaikovsky, 19 February/3 March 1879.

- ↑ Letter 1258 to Nadezhda von Meck, 16/28–17/29 August 1879. He also asked for Russian or French translations of any Dickens novels she might have to hand.

- ↑ See also Kadja Grönke, On the role of Gremin. Tchaikovsky's Eugene Onegin (1998). Kadja Grönke shows how the music of Gremin's aria in tribute to his wife influences that of the opera's final scene, giving Tatyana the maturity and inner strength to reject Onegin's advances not out of fear of society but out of a true sense of duty (p.223–231).

- ↑ See letter 748 to Karl Albrecht, 3/15 February 1878, quoted in the work history for Yevgeny Onegin.

- ↑ See also letter 1614 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 17/29 October 1880, also quoted in the work history for Yevgeny Onegin.

- ↑ Herman Laroche's review is quoted in: Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 167.

- ↑ From Dostoyevsky's Pushkin address in: V. A. Bogdanov (ed.), Ф. М. Достоевский об искусстве (1973), p. 360.

- ↑ Rolf-Dieter Kluge, Čajkovskij und die literarische Kultur Russlands (1995), p.166–167.

- ↑ This stage direction (from the full score published in December 1880) is quoted here from the notes by David Lloyd-Jones for his translation of the libretto of the opera in Eugene Onegin (1988), p. 93.

- ↑ See also Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 167.

- ↑ We know that Taneyev was present at the Pushkin festivities from his letter of 25 July/6 August 1880 to Tchaikovsky, in which he argued that music in the West was degenerating, and that Russia could avoid falling into the same trap by turning to Russian folk-song with the requisite affection and respect, since folk art was the basis of all literature and music. Taneyev pointed out in this letter how Bach had created German music from the chorale, which grew out of folk melodies, and how the Gregorian chants which became the basis for Italian music in the 16th century were also derived from folk tunes. In Taneyev's view it was always the long-suffering common folk which unconsciously accumulated the material that would later feed into higher works of art, and he added: "At the Pushkin festivities I was very pleased to hear about a detail of his biography which had hitherto escaped my notice — towards the end of his life Pushkin started writing down folk idioms and listening to how simple people talked. 'One ought to learn the Russian language from the village-women who make communion bread' — those are his own words. We should remember these words and turn our eyes towards the people." This letter is quoted in П. И. Чайковский. С. И. Танеев. Письма (1951), p. 55.

- ↑ Letter from Mariya Klimentova to Dostoyevsky, 30 June/12 July 1880. Quoted in: Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 166.

- ↑ Letter from Anatoly Tchaikovsky to the composer, 22 October/3 November 1880. Quoted in: Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 168–169. The Diary of a Writer (Дневник писателя) was an ongoing project which Dostoyevsky had started in 1873 alongside his main literary work, and which consisted of brief articles where he could share his thoughts with readers about various current affairs in Russian society. Because of his uncompromising sincerity and vivid style, these articles soon became very popular. Dostoyevsky also published some of his finest short stories in the pages of The Diary of a Writer: e.g. The Meek One (1876) and The Dream of a Ridiculous Man (1877). His speech on Pushkin was reprinted in the August 1880 issue of The Diary of a Writer. As Polina Vaidman has pointed out at the end of her Dostoyevsky article for the Belcanto Tchaikovsky Pages (in Russian), a remark in one of Tchaikovsky's notebooks proves that he had himself also read Dostoyevsky's Pushkin speech.

- ↑ Many of the verses for Gremin's aria in the opera are indeed Pushkin's, but taken from other sections of the novel and quite unrelated to the figure of Tatyana's husband as such. Some key verses, however, were written by Tchaikovsky himself (possibly with the help of his co-librettist Konstantin Shilovsky).

- ↑ Abram Gozenpud, Dostoyevsky and the Musical and Dramatic Arts (1981), p. 167.

- ↑ See also the laconic diary entry for 11/23 January 1889: "Read Dostoyevsky (The Double)" and the much more revealing entry for 17/29 January 1889: "Am reading What I Believe in the mornings, and I marvel at this combination of wisdom and childish naivety." See Дневники П. И. Чайковского (1873-1891) (1993), p. 220–221. A diary entry a few days earlier, for 15/27 January, also records that he had had a discussion about Tolstoy with Sergey Taneyev and Aleksandr Ziloti, who had come to visit him in Frolovskoye.

- ↑ In that letter to Yuliya Shpazhinskaya (letter 3210) Tchaikovsky argued that "the principal trait, or, rather, the keynote which always sounds in every page written by Tolstoy, no matter how seemingly insignificant its content might be, is love, compassion for man in general (not just for the insulted and injured)", and, as Rolf-Dieter Kluge, Čajkovskij und die literarische Kultur Russlands (1995), p. 169, has pointed out, the last phrase is a clear allusion to Dostoyevsky's 1861 novel of that title, The Insulted and Injured (Униженные и оскорблённые).

- ↑ See Дневники П. И. Чайковского (1873-1891) (1993), p. 83–84. Eugène-Melchior, vicomte de Vogüé (1848–1910), French diplomat and author; he wrote a valuable monograph on Russian literature: Le roman russe (Paris, 1886). Paul Bourget (1852–1935), French writer and critic; one of his Essais de psychologie contemporaine (Paris, 1883) dealt with Turgenev.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky is referring to Chapter 3 in Book II of Part 1 of The Brothers Karamazov, which was then being serialized in the Russian Messenger (Русский вестник). In this chapter of the novel Dostoyevsky also expressed his own grief at the death of his three-year-old son Alesha in 1878.

- ↑ The last instalment of Dostoyevsky's novel appeared in the November 1880 issue of the Russian Messenger, but already in December the complete novel was published separately as a two-volume edition. It seems that Tchaikovsky had purchased a copy of this edition and read the later chapters of the novel in that format rather than in the Russian Messenger as they came out.