Letter 759

| Date | 13/25 February–14/26 February 1878 |

|---|---|

| Addressed to | Anatoly Tchaikovsky |

| Where written | Florence |

| Language | Russian |

| Autograph Location | Klin (Russia): Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve (a3, No. 1152) |

| Publication | П. И. Чайковский. Письма к родным (1940), p. 372–377 (abridged) П. И. Чайковский. Письма к близким. Избранное (1955), p. 149–150 (abridged) П. И. Чайковский. Полное собрание сочинений, том VII (1962), p. 113–118 (abridged) Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky. Letters to his family. An autobiography (1981), p. 146 (English translation; abridged) Неизвестный Чайковский (2009), p. 237–242 |

Text and Translation

| Russian text (original) |

English translation By Brett Langston |

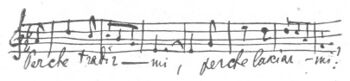

Флоренция 13-го/25 февр[аля] 1878 Вчера, после моего письма, я тотчас же получил твоё, но отвечаю только сегодня, так как мне пришлось вечером написать несколько писем и я устал, а мне хочется поговорить несколько подробнее по поводу при знания, которое ты мне сделал. Мне очень, очень грустно, Толя, что ты так хандришь. Утешать тебя я не буду, ибо ты не без основания говоришь, что, в сущности, жаловаться нечего. Но, пользуясь привилегию своей относительной старости, могу тебе дать несколько советов. Все то, что ты испытываешь, мне очень, очень знакомо. По-моему, имеются две причины твоей хандре: 1) нервность, вследствие которой часто тоска нападает без всякой причины, и 2) болезненное самолюбие. Вторая причина, конечно, важнее первой, ибо она-то, приводя тебя в состояние раздражения, действует дурно на нервы. Вот об этом-то я и хочу с тобой поговорить. В сущности, то, что ты испытываешь, составляет явление самое обыкновенное. Я не знаю ни одного человека из моих знакомых, т. е. из тех, которые одарены умом и вообще более тонкой организацией, которые бы не терзались тем самым недовольством, той самою неудовлетворённостью стремлений, которая составляет твою болезнь. Все они считали себя призванными на что-то очень необыкновенное и оказались или совсем неудавшимися, или хотя и вполне удавшимися, как ты, но не достигшими той высоты, на которую рассчитывали. Я не буду входить в рассмотрение того вопроса, насколько ты имел право считать себя человеком, выходящим из ряда, ибо я не знаю, на что ты надеялся. С моей точки зрения, ты удался вполне. Я никогда не питал особенного желания, чтоб из тебя вышел гениальный учёный юрист или вообще великий человек. Я тебя любил и люблю так, как ты есть. Я всегда считал тебя умным, добрым, благородным, симпатичным и дельным человеком, т. е. таким, который пробьёт себе хорошую дорогу, составит себе независимое положение, будет всеми любим. Все это исполнилось, и твои успехи как на службе, так и в обществе не подлежат никакому сомнению. Если ты говоришь, что твоя амбиция состоит только в том, чтоб ты был талантливым прокурором, то ведь это вполне сбылось. Про тебя именно все говорят, что ты талантливый прокурор, и никто в этом не сомневается. Что ты умён и необыкновенно симпатичен, — это тоже признано всеми. Что ты тонкая и благородная натура, что ты при над лежишь к числу избранных, т. е. имеющих способность высшего понимания, это факт, не подлежащий спору. Вообще ты одна из тех редких личностей, которые вселяют всем неотразимую симпатию. Если для тебя всего этого мало, — ты не вполне искренен, когда говоришь, что только того и хочешь, чтобы быть хорошим прокурором. Впрочем, повторяю, что я не хочу входить в подробности относительно того, есть или нет в тебе задатки великой будущности. Ты знаешь, что великий человек никогда не бывает велик для своей кухарки. Это положение можно расширить, т. е. сказать, что великий человек не кажется великим для своего брата. Я тебе говорю совершенно откровенно, что я тебя всегда считал обаятельно симпатичным человеком, т. е. таким, в котором все качества оставляют нечто гармоническое и цельное. Мне кажется, что секрет симпатичности кроется именно в этой гармоничности когда ни одно качество не развито в ущерб другому. Итак, чтоб покончить с этим, скажу, что я рассчитывал для тебя на блестящую и завидную будущность и что в моих глазах ты очень последовательно идёшь к той цели, которую я в своих мыслях для тебя назначил. Если ты не поддашься своей хандре и не падёшь духом, то я убеждён, что ты достигнешь очень высокого положения в обществе, ибо именно у тебя есть все данные для блестящей карьеры и для счастливой жизни. Так как я не замечал в тебе какой-нибудь преобладающей способности (как, напр[имер], у меня к музыке), то полагал, что ты пойдёшь по широкой общей стезе и что на этой стезе, благодаря вышеупомянутой гармонической цельности твоей чудной натуры, ты займёшь не последнее место. Весьма может быть, что я ошибаюсь, т. е. что ты имеешь основание считать себя неудавшимся, — но я тебе пишу откровенно что думаю, ибо надеюсь, что от этого произойдёт польза. Вот что я хотел тебе объяснить: нет ничего бесплоднее, как те страдания, которые причиняет неумеренное самолюбие. Я это говорю потому, что сам вечно страдал тем же и тоже никогда не был доволен теми результатами, которых достиг. Ты, может быть, скажешь, что так как обо мне пишут в газетах, — то я знаменит и должен быть счастлив и доволен. А между тем мне этого мало et j'ai toujours voulo[ir] péter plus haut que mon cul. Я хотел быть не только первым композитором в России, но и в целом мире; я хотел быть не только композитором, нон первоклассным капельмейстером; я хотел быть необыкновенно умным и колоссально знающим человеком; я также хотел быть изящным и светским и уметь блистать в салонах; мало ли чего я хотел. Только мало-помалу, ценой целого ряда невыносимых страдании, я дошёл до сознания своей настоящей цены. Вот от этих-то страданий я и хотел бы уберечь тебя. Мне смешно вспомнить, напр[имер], до чего я мучился, что не могу попасть в высшее общество и быть светским человеком! Никто не знает, сколько из-за этой пустяковины я страдал и сколько я боролся, чтоб победить свою невероятную застенчивость, дошедшую одно время до того, что я терял за два дня сон и аппетит, когда у меня в виду был обед у Давыдовых!!! А сколько тайных мук я вынес, прежде чем убедился, что совершенно неспособен быть капельмейстером! Сколько времени нужно было мне, чтоб прийти к убеждению, что я принадлежу к категории неглупых людей, а не к тем, ум которых имеет какие-нибудь особенно выдающиеся стороны? Сколько лет мне нужно было, дабы понять, что даже как композитор, — я просто талантливый человек, а не исключительное явление. Только теперь, особенно после истории с женитьбой, я, наконец, начинаю понимать, что ничего нет бесплоднее, как хотеть быть не тем, что я есть по своей природе. Между тем жизнь коротка, и мудрый человек, вместо того чтобы хандрить, мучиться от неудовлетворенного самолюбия, терять время на бесплодные сожаления о неисполнившихся мечтаниях, должен наслаждаться жизнью. И знаешь, Толя! Я даже рад, что ты не имеешь какого-нибудь особенного художественного дарования, указывающего на исключительный путь. Всякий такой человек встречает на каждом шагу тьму препятствий, интриг, дух партий, неприязненность, соперничество и т. д. Между тем, идя по общей стезе, т. е. просто добиваясь посредством службы независимого положения, можно устроить себе отличную жизнь. Самолюбию нужно давать волю как раз настолько, чтобы оно служило стимулом к восходящему движению карьеры, и добросовестно исполнять своё дело, от давая ему столько сил и времени, сколько нужно, чтобы дело делалось. В тебе от природы есть эта добросовестность, и она служит ручательством, что ты никогда не запустишь себя до компрометирования своего положения. Не следует смущаться, что другие, менее достойные и менее способные, идут быстрее. Если я в музыкальной сфере примирился с тем, что люди, менее меня способные, достигли гораздо больше славы и лучших средств, то в сфере службы тебе непременно следует примириться с этими несправедливостями рока, ибо в службе личные отношения и случай играют большую роль, чем где-либо. Я все боюсь, что в пылу своего усердия принести тебе пользу неясно выражаю свою мысль. Из твоего письма я вижу, что ты постоянно переходишь от веры в свои необычайные силы к упадку духа и непризнаванию должной цены себе. Я тебе хочу указать середину между тем и другим. Ты une nature supérieure без одной какой-либо выдающейся способности. Поэтому ты имеешь право с высоты смотреть на жизнь, на неизбежность частого торжества бездарности и пошлости и, примирившись с этим, вести жизнь спокойного созерцателя. Если ты, напр[имер], начнёшь читать больше, чем читал до сих пор, — сколько наслаждений ты себе доставишь! Чтение есть одно из величайших блаженств, когда оно сопровождается спокойствием в душе и не делается урывками, а постоянно. Искусство даёт тоже много приятных минут. Наконец, при твоей способности всем нравиться, и общество украсит твою жизнь, если ты опять-таки не поддашься болезненному самолюбию и не захочешь блистать во что бы то ни стало больше всех. Общество приятно тогда, когда входишь в него не с целью затмить всех своей бонтонностью, своим умом и т. д., а для того, чтобы наблюдать и изучать людей, оставив в стороне амбицию. Впрочем, насколько я тебя знаю, у тебя бездна такта, естественности, простоты и врождённой комильфотности, так что не мне учить тебя, как пользоваться обществом. Кончаю, буду продолжать завтра. Флор[енция] 14/26 Я собирался сегодня продолжать мои наставления н хотел подробно поговорить насчёт одной важной стороны твоей жизни или, лучше, твоего недовольства жизнью. Я хотел распространиться о том, что я замечал в тебе стремление к начитанности и приобретению всякого рода сведений. Между тем, я замечал, что причина этого стремления заключается в тебе не в силу непосредственного желания знать, а в силу того, чтобы кичиться своими знаниями или превзойти того или другого из твоих знакомых по части образованности. Между тем, чтение только тогда наслаждение, когда оно само по себе цель, а не средство достижения посторонних, основанных на ложном самолюбии целей. Да! я хотел распространиться об этом и о многом другом, как вдруг получил твоё письмо в форме дневника, из которого вижу совершенно ясно, что ты просто влюблён. Я рад этому, хотя мне и жалко было читать, что любовь отнимает у тебя сон. Рад потому, что любовь наполнит твою жизнь, и потом, мне кажется, что Панаева не может не влюбиться в тебя, и я предвижу, что выйдет из всего этого что-нибудь хорошее. Как мне приятно было читать твой дневник! Мне кажется, что это лучшая форма для переписки. Это первое твоё письмо, из которого я мог получить ясное понятие о том, как ты живёшь. Я так живо представлял себе тебя и в концерте, и у Палкина, и дома во время бессонницы! Я читал твой дневник, как самый прелестный роман. Однако ж следует и мне за свой приняться. Третьего дня (воскресение) мы ездили кататься за город и совершили приятную прогулку. Между прочим, очень поэтическое воспоминание оставил во мне монастырь des chartreux. Вечером я ходил по набережной в тщетной надежде услышать где-нибудь знакомый чудный голосок: Встретить и ещё раз услышать пение этого божественного мальчика сделалось целью моей жизни во Флоренции. Куда он исчез? Вчера утром написал пиэсу для фортепьяно. Я положил себе каждый день писать по пиэсе. После завтрака ходили в Palazzo Pitti. Вечером я опять ходил до усталости по набережной, все в надежде увидеть моего милого мальчика. Вдруг вижу вдали сборище, пение, сердце забилось, бегу и о, разочарование! Пел какой-то усатый человек, и тоже хорошо, — но можно ли сравнивать? На возвратном пути домой (мы живём далеко от набережной) я был преследуем юношей необычайной, классической красоты и совершенно по-джентльменски одетым. Он даже вступил в разговор со мной. Мы прогуляли с ним около часу. Я очень волновался, колебался и наконец сказав, что меня ждёт дома сестра, расстался с ним, назначив на послезавтра, rendez-vous, на которое пойду. Весь вечер мы говорили с Модестом про тебя. Он мне прочёл несколько глав из своего дневника, писанного осенью. Поразительно, до чего его недовольство собой сходно с твоим. Он точно так же, как и ты, падает иногда духом, считает себя мелкой душонкой и т. д. В сущности же, я тебе скажу, что ты и Модест составляете самую пленительную красу человечества и что ничего лучшего, ничего более отрадного нет в моей жизни, как вы оба, каждый в своём роде. Даже самые недостатки ваши симпатичны. Пожалуйста, дорогой мой, воспрянь духом, не бойся сравнения ни с кем. Примирись с тем, что есть люди более умные и более талантливые, чем ты, — но проникнись убеждением, что у тебя есть та гармония, о которой я вчера писал, и эта гармония ставит тебя безгранично выше большинства людей. Ну что толку в том, что Ларош умнее нас с тобой? Что толку в том, Что Апухтин остроумнее нас с тобой? Я бы бросился в реку или застрелился бы, если б Ларош и Апухтин вдруг сделалась моими братьями, а ты приятелем! Если Панаева тебя полюбит, я напишу ей целый цикл романсов, вообще сделаюсь её благодарным рабом. Посылаю тебе это письмо не в очередь. Не хочу ждать до завтра. Карточка твоя была покрыта поцелуями. Завтра я отошлю её, к Н[адежде] Ф[иларетовне]. Твой П. Чайковский Обнимаю тебя до удушения. |

Florence 13th/25 February 1878 Yesterday, after my letter, I received yours right away, but I'm only answering today, since I had to write several letters in the evening and I was tired, and I wanted to talk in some more detail regarding the news that you gave me. I'm very, very sorry, Tolya, that you are so miserable. I won't console you, because you say, not without reason, that there's nothing to complain about. But, taking advantage of the privilege of my relative old age, I can give you some advice. Everything that you are experiencing is very, very familiar to me. In my opinion, there are two reasons for your misery: 1) nerves, as a result of which unhappiness often strikes without any reason, and 2) injured pride. The second reason, of course, is more important than the first, because it brings you to a state of agitation, having a bad effect on your nerves. It is this that I want to talk to you about. In essence, what you are experiencing is a most commonplace occurrence. I don't know a single person amongst my acquaintances, i.e. of those who are endowed with intelligence and generally with a more refined disposition, who would not be tormented by that same dissatisfaction, that same frustration of ambition which your malaise comprises. They all considered themselves to have a most exceptional calling, and which turned out to be either altogether unsuccessful, or although quite successful, like you, they did not achieve the heights they had anticipated. I won't enter into considering the question of to what extent you had the right to consider yourself an exceptional person, because I don't know what you were hoping for. From my point of view, you were quite successful. I never harboured any particular desire for you to become an ingenious, learned lawyer, or even a great man in general. I loved you and love you as you are. I have always considered you an intelligent, kind, honourable, sympathetic and business-like person, that is one who will make cut his own path, create an independent position for himself, and will be loved be everyone. All this has come to pass, and your successes both in employment and in society are beyond any doubt. If you say that your only ambition is to make a talented prosecutor, then this has absolutely come true. Indeed, everyone says that you are a talented prosecutor, and nobody doubts this. That you are intelligent and exceptionally handsome is also recognised by everyone. That you are refined and honourable by nature, that you are counted amongst the chosen ones, i.e. those who have a quality of higher understanding, this fact is not subject to dispute. Generally you are one of those rare individuals who inspire irresistible sympathy in everyone. If this is all too little for you, then you are not entirely sincere when you say that all you want is to be a good prosecutor. However, I repeat that I don't want to go into details regarding whether or not you have the makings of a great future. You know that a great man is never too great for his cook. This analogy can be extended, i.e. to say that a great man doesn't seem great to his brother. I'll tell you quite frankly that I've always considered you a charmingly sympathetic person, i.e. one whose qualities produce something harmonious and well-rounded. It seems to me that the secret to being sympathetic lies precisely in this harmony, where no-one quality is developed to the detriment of another. Therefore, to finish with this, I'll say that I was counting on a brilliant and enviable future for you, and that in my eyes you are very consistently moving towards the goal that I have set for you in my thoughts. If you don't succumb to your misery, and don't lose heart, then I'm convinced that you'll achieve a very high position in society, because you who have everything needed for a brilliant career and for a happy life. Since I haven't noticed any predominant ability in you (as, for example, I have for music), I believed that you would follow a generally broad path, and that on this path, thanks to the aforementioned harmonious integrity of your wonderful nature, you won't find yourself in last place. It's quite possible that I'm mistaken, i.e. that you have reason to consider yourself a failure — but I'm writing to you what I think frankly, because I hope that some good will come from this. This is what I wanted to explain to you: there is nothing more fruitless than the suffering caused by immoderate pride. I say this because I myself always suffered with the same thing, and I was never satisfied with the results which I achieved. You may say that since they write about me in the newspapers, then I am famous and should be happy and contented. Meanwhile, this is too little for me, et j'ai toujours vouloir péter plus haut que mon cul. I wanted not only to be the foremost composer in Russia, but in the whole world; I wanted not only to be a composer, but also a first-class kapellmeister; I wanted to be an exceptionally clever and colossally knowledgeable person; I also wanted to be elegant and worldly, and to be able to shine in salons. I knew little of why I wanted this. Only little-by-little, at the cost of a whole series of unbearable sufferings, did I come to realise my true worth. It is from this suffering that I should like to spare you. It's funny for me to remember, for example, how much I suffered that I couldn't make it into high society and be a worldly fellow! Nobody knows how much I suffered because of this frippery, and how much I fought to overcome my incredible shyness, which once reached the point that I lost my sleep and appetite for two days when I was thinking about dinner at the Davydovs!!! And how many secret torments I endured before I became convinced that I was utterly incapable of being a kapellmeister! How long it took me to become convinced that I belonged to the category of not stupid people and not to those whose minds have any particularly outstanding aspects. How many years did it take me to understand that even as a composer, I was simply a talented person, and not an exceptional phenomenon. Only now, especially after the story with my marriage, am I finally starting to understand that there is nothing more fruitless than wanting to be something other than what I am by nature. Meanwhile, life is short, and a wise person, instead of being miserable, suffering from unsatisfied pride, wasting time on fruitless regrets about unfulfilled dreams, should enjoy life. And you know, Tolya! I'm even glad that you don't have some sort of special artistic gift which points towards an exceptional path. At every step such a person encounters a host of obstacles, intrigues, partisanship, hostility, rivalry, etc. Meanwhile, by following a general path, i.e. simply achieving an independent position through employment, you can organise a splendid life for yourself. Self-love needs to be given free reign just enough so that it serves as a stimulus for moving one's career upward, and one must carry out one's work conscientiously, giving it as much time and effort as is necessary to do what has to be done. You have this conscientiousness by nature, and it serves as a guarantee that you will never forsake yourself to the point of compromising your position. You should not be embarrassed that others, less worthy and less capable, go faster. If in the musical sphere I've had to reconcile myself to the fact that people less capable than me have achieved far more praise and better means, then in the field of employment you should certainly reconcile yourself to these injustices of fate, because at work, personal relationships and chance play a greater role than anywhere else. I'm still afraid that in the heat of my eagerness to be of some use to you, I'm not expressing my thoughts clearly. From your letter, I see that you are constantly wavering between a belief in your extraordinary powers and discouragement and a failure to recognise your own worth. I want to show you there is a position between one and the other. That you have une nature supérieure without some sort of outstanding ability. Therefore you have the right to look at life from above, at the inevitability of the frequent triumph of mediocrity and vulgarity, and, having reconciled yourself to this, to lead a calm and contemplative life. If you, for example, start to read more than you have read before, then how much pleasure you will give yourself! Reading is one of the greatest blessings when it is accompanied by peace in the soul, and isn't done in fits and starts, but continually. Art can also provide many pleasant moments. Finally, with your ability to please everyone, society will enhance your life, if you, again, don't succumb to injured pride and don't want to shine more than anyone else at all costs. Society is pleasant when you enter it not with the goal of outshining everyone with your manners, your intelligence, etc. but in order to observe and to study people, leaving ambition aside. Anyway, so far as I know you have plenty of tact, spontaneity, simplicity and innate comme il faut, so it isn't for me to teach you how to use society. I'm finishing, I'll continue tomorrow. Florence 14/26 I had intended to continue my instructions today and wanted to talk in detail regarding one important aspect of your life, or rather your dissatisfaction with life. I wanted to announce that I've noticed in you a desire to be weell-read and to acquire all sorts of information. Meanwhile, I noticed that the reason for this desire lies not in the stength of your desire to find out first-hand, but in so that you can boast about your knowledge or trump one or another of your acquaintances in terms of scholarship. Meanwhile, reading is only a pleasure when it is a goal in itself, and not a means of extraneous achievements based upon false goals. Indeed! I wanted to talk about this and much more, when suddenly I received your letter in the form of a diary, from which I can see quite clearly that you are simply in love. I am glad about this, although I was sorry to read that your love is depriving you of sleep. I'm glad because your life will be filled with love, and then, it seems to me, that Panayeva cannot help but fall in love with you, and I foresee that something good will come out of all this. I was so pleased to read your diary! It seems to me that this is the best form for correspondence. This was the first letter from you from which I could form a clear idea of how you live. I imagined you so vividly at the concert, at Palkin's, and at home during your insomnia! I read your diary like a most charming novel. However, I ought to start saying something about myself. Two days ago (Sunday) we went for a ride outside the city and managed a pleasant walk. Along the way, the monastery des chartreux left me with a most poetic memory. In the evening I walked along the embankment in the vain hope of hearing somewhere a familiar, wonderful little voice: To meet and once again her the singing of this heavenly boy became the goal of my life in Florence. Where did he disappear to? Yesterday morning I wrote a piece for piano. I've made a point of writing a piece every day. After lunch we went to the Palazzo Pitti. In the evening I walked again up to the embankment, still with every hope of seeing my dear boy. Suddenly I see a gathering in the distance, singing, my heart is pounding, I run and — oh, disappointment! Some moustachioed man was singing, just as well, but how can it compare? Retuning home (we live a long way from the embankment), I was pursued by a young man of extraordinary, classical beauty and dressed completely like a gentleman. He even struck up a conversation with me. We walked together for about an hour. I was very worried and hesitant, finally saying that my sister was waiting for me at home, and parted from him, fixing a rendz-vous that I would go to the day after tomorrow. Modest and I talked about you all evening. He read me several chapters from his diary, written during the autumn. It's astonishing how his own dissatisfaction with himself is so similar to yours. He, just like you, sometimes loses heart, considers himself a petty soul, etc. In essence, I'll say to you that you and Modest constitute the most captivating beauty of humanity, and there is nothing better, nothing more joyful in my life than the both of you, each in your own way. Even your flaws are so sympathetic. Please, my dear fellow, take heart, and do not be afraid of comparison with anyone. Reconcile yourself to the fact that there are more intelligent and more talented people than you, but be filled with the conviction that you have that harmony that I wrote about yesterday, and this harmony places you infinitely higher than the majority of people. Well, what does it matter that Laroche is cleverer than you and me? What of it that Apukhtin is wittier than you and me? I would throw myself into the river or shoot myself if Laroche and Apukhtin suddenly became my brothers, and you my friend! If Panayeva loves you, I'll write her a whole cycle of romances, and become her grateful slave in general. I'm sending you this letter out of order. I don't want to wait until tomorrow. Your picture was covered with kisses. Tomorrow I'll send it off to Nadezhda Filaretovna. Yours P. Tchaikovsky I hug you to suffocation. |