Letter 2158 and Herman Klein: Difference between pages

m (1 revision imported) |

m (Added "he" for clarity of meaning) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

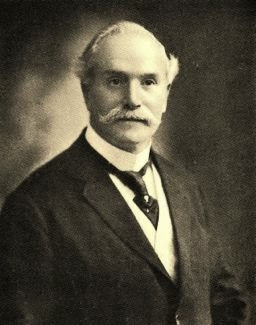

{{ | {{picture|file=Herman Klein.jpg|caption='''Herman Klein''' (1856-1934)}} | ||

| | English music critic, author, and teacher of singing (b. 11/23 July 1856 in Norwich; d. 10 March 1934 in [[London]]), also known as '''''Hermann Klein''''' <ref name="note1"/>. | ||

| | |||

== | ==Biography== | ||

Klein began his career as a vocal teacher at the Guildhall School of Music in [[London]]. In 1876 he took up musical journalism, writing for ''The Sunday Times'' from 1881–1901, and also contributed prolifically to ''The Musical Times'', amongst other publications. In 1901 Klein moved to [[New York]], where he wrote for ''The New York Herald'' while continuing to work as a singing tutor. He was one of the first critics to take notice of the gramophone and was appointed "musical adviser" to Columbia Records in 1906 in [[New York]]. He returned to England in 1909. | |||

Klein wrote over half a dozen books about music and singers, as well as English translations of operas and art songs. He was a noted authority on Gilbert and Sullivan. In 1924, he began writing for ''The Gramophone'' and was in charge of operatic reviews, as well as contributing a monthly article on singing, from then until his death. | |||

==Tchaikovsky and Klein== | |||

Klein first encounter with Tchaikovsky was at a concert in [[London]] on 10/22 March 1888, which he described in his capacity as music critic of ''The Sunday Times'' <ref name="note2"/>: | |||

{{quote|M. Tschaikowsky made his first bow — or, rather, the first of several very profound and rapid bows — before an English audience at the Philharmonic Concert on Thursday. A hearty reception awaited him as was fitting in the case of one of the most distinguished of Russian composers [...] M. Tschaikowsky is not quite forty-eight, but he looks older, his hair and close-cut beard being perfectly grey. By his intelligent and animated beat, I should judge him to be a good conductor. It was a pity, though, that he should not have been represented in Thursday's scheme by a work of first-class importance, instead of a [[Serenade for Strings]] and a movement of a suite <ref name="note3"/>, neither of them worthy of this genius in its highest phase. The predominant impression left behind is tinged with a certain coarseness, not to say vulgarity of treatment. M. Tschaikowsky had to respond to two recalls after the [[Serenade for String Orchestra|Serenade]], which brought out the tone of the Philharmonic strings with wonderful sonorousness and purity of quality <ref name="note4"/>.}} | |||

When Tchaikovsky returned to England in the summer of 1893 to collect his honorary doctorate of music from [[Cambridge]] University, he found himself sharing a railway carriage with Klein on the journey from [[London]] to [[Cambridge]]. Klein recalled the occasion at length in his memoirs, published ten years later <ref name="note5"/>: | |||

{{quote|In the autumn of 1892 the Russian master's opera "[[Yevgeny Onegin|Eugény Onégin]]" was produced in English at the Olympic Theatre, under the management of Signor Lago, with [[Eugène Oudin]] in the title part <ref name="note6"/>. It met with poor success, and after a few nights was withdrawn <ref name="note7"/>.}} | |||

{{quote|In the June of 1893, Tschaikowsky came to England to receive the honorary degree of "Mus. Doc." at [[Cambridge]] University; the same distinction being simultaneously bestowed upon three other celebrated musicians — [[Camille Saint-Saëns]], Max Bruch, and Arrigo Boïto. By a happy chance I travelled down to Cambridge in the same carriage with Tschaikowsky. I was quite alone in the compartment until the train was actually starting, when the door opened and an elderly gentleman was unceremoniously lifted in, his | |||

luggage being bundled in after him by the porters. A glance told me who it was. I offered my assistance, and, after he had recovered his breath, the master told me he recollected that I had been presented to him one night at the Philharmonic. Then followed an hour's delightful conversation.}} | |||

{{quote|Tschaikowsky chatted freely about music in Russia. He thought the development of the past twenty-five years had been phenomenal. He attributed it, first, to the intense musical feeling of the people which was now coming to the surface; secondly, to the extraordinary wealth and characteristic beauty of the national melodies or folk-songs; and, thirdly, to the splendid work done by the great teaching institutions at [[St. Petersburg]] and [[Moscow]]. He spoke particularly of his own Conservatory at Moscow, and begged that if I ever went to that city I would not fail to pay him a visit <ref name="note8"/>. He then put some questions about England and inquired especially as to the systems of management and teaching pursued at the Royal Academy and the Royal College. I duly explained, and also gave him some information concerning the Guildhall School of Music and its three thousand students. It surprised him to hear that [[London]] possessed such a gigantic musical institution.}} | |||

{{quote|"I don't know", he added, "whether to consider England an 'unmusical' nation or not. Sometimes I think one thing, sometimes another. But it is certain that you have audiences for music of every class, and it appears to me probable that before long the larger section of your public will support the best class only". Then the recollection of the failure of his "[[Yevgeny Onegin|Eugény Onégin]]" occurred to him, and he asked me to what I attributed that — the music, the libretto, the performance, or what? I replied, without flattery, that it was certainly not the music. It might have been due in some measure to the lack of dramatic fibre in the story, and in a large degree to the inefficiency of the interpretation and the unsuitability of the locale. "Remember," I went on, "that [[Pushkin]]'s poem is not known in this country, and that in opera we like a definite dénouement, not an ending where the hero goes out at one door and the heroine at another. As to the performance, the only figure in it that lives distinctly and pleasantly in my memory is [[Eugène Oudin]]'s superb embodiment of ''Onégin''".}} | |||

{{ | |||

{{quote|"I have heard a great deal about him", said Tschaikowsky; and then came a first-rate opportunity for me to descant upon the merits of the American barytone. I aroused the master's interest in him to such good purpose that he promised not to leave England without making his acquaintance, — "and hearing him sing?" I queried. "Not only will I hear him sing, but invite him to come to Russia and ask him to sing some of my songs there", was the composer's reply as the train drew up at [[Cambridge]], and we alighted <ref name="note9"/>. Tschaikowsky was to be the guest of the Master of Merton <ref name="note9a"/>, and I undertook to see him safely bestowed at the college before proceeding to my hotel. Telling the flyman to take a slightly circuitous route, I pointed out various places of interest as we passed them, and Tschaikowsky seemed thoroughly to enjoy the drive. When we parted at the college, he shook me warmly by the hand and expressed a hope that when he next visited England he might see more of me. Unhappily, that kindly wish was never to be fulfilled.}} | |||

I | |||

{{quote|The group of new "Mus. Docs." was to have included [[Verdi]] and [[Grieg]] <ref name="note9b"/>, but these composers were unable to accept the invitation of the University. However, the remaining four constituted a sufficiently illustrious group, and the concert at the [[Cambridge]] Guildhall was of memorable interest. [[Saint-Saëns]] played for the first time the brilliant pianoforte fantasia "Africa", which he had lately written at Cairo; Max Bruch directed a choral scene from his "Odysseus"; and Boïto conducted | |||

the prologue from "Mefistofele", [[George Henschel|Georg Henschel]] singing the solo part. Finally, Tschaikowsky directed the first performance in England of his fine symphonic poem, "[[Francesca da Rimini]]", a work depicting with graphic power the tormenting winds wherein [[Dante]] beholds Francesca in the "Second Circle" and hears her recital of her sad story, as described in the fifth canto of the | |||

"Inferno". The ovation that greeted each master in turn will be readily imagined. A night or two later I met Boïto at a reception given in his honour by my friend Albert Visetti, and the renowned librettist-composer did me the pleasure of accompanying me to the last Philharmonic concert of the season, at which Max Bruch conducted a couple of works and Paderewski played his concerto in A minor.}} | |||

{{quote|Tschaikowsky and [[Eugène Oudin]] duly met. The latter sang the "Serenade de Don Juan" <ref name="note10"/> and other songs of the Russian master, and so delighted him that the visit to [[St. Petersburg]] and [[Moscow]] was immediately arranged.}} | |||

==Bibliography== | |||

* {{bib|1888/13}} (1888) | |||

* {{bib|1903/10}} (1903) | |||

* {{bib|1903/11}} (1903) | |||

* {{bib|1903/12}} (1903) | |||

* {{bib|1973/50}} (1973) | |||

* {{bib|1978/28}} (1978) | |||

* {{bib|1979/54}} (1979) | |||

* {{bib|1980/76}} (1980) | |||

* {{bib|1993/99}} (1993) | |||

* {{bib|1994/75}} (1994) | |||

* {{bib|1999/48}} (1999) | |||

==External Links== | |||

* [[wikipedia:Herman Klein|Wikipedia]] | |||

==Notes and References== | ==Notes and References== | ||

<references> | <references> | ||

<ref name="note1"> | <ref name="note1">In his 1903 autobiography {{bib|1903/11|Thirty years of musical life in London, 1870-1900}} (1903) his name was spelled as "Hermann Klein", but government records of his birth and death confirm that "Herman" was his official forename.</ref> | ||

<ref name=" | <ref name="note2">See {{bib|1888/13|Music and Musicians}} (1888).</ref> | ||

<ref name="note3">The ''Theme and Variations'' from the [[Suite No. 3]].</ref> | |||

<ref name="note4">Extracts quoted in {{bib|1999/93|Tchaikovsky through others' eyes}} (1999), p. 157.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note5">{{bib|1903/11|Thirty years of musical life in London, 1870-1900}} (1903), p. 343-350.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note6">The premiere took place on 5/17 October 1892 at the Olympic Theatre, with a cast including Madame Selma (Larina), Fanny Moody (Tatyana), Lily Moody (Olga), [[Aleksandra Svyatlovskaya]] (Filippyevna), Eugène Oudin (Onegin), Iver McKay (Lensky), and Charles Manners (Gremin), conducted by Henry Wood.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note7">"The whole undertaking was ill-timed and ill-placed" — ''Klein's footnote''.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note8">"I did visit [[Moscow]] in the summer of 1898, and, on presenting my card as an English friend of the lamented master, was received by the Conservatory officials with every attention and cordiality" — ''Klein's footnote''.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note9">Gerald Norris, however, has pointed out that in the earliest description of this conversation published by Klein (in the ''Sunday Times'' of 12 November 1893 {{NS}}), Tchaikovsky's words are reported slightly differently: "I have heard [[Oudin]], and I am sure he at least must have been excellent" [as Onegin]. This would suggest that Tchaikovsky had already made the acquaintance of [[Oudin]] and even heard him sing. In fact, as Norris argues, the composer had almost certainly attended [[Eugène Oudin|Eugène]] and Louise Oudin's afternoon recital in Saint James's Hall, [[London]], on 20 May/1 June 1893, a few hours before he himself conducted, in the same venue, the first performance in England of his [[Fourth Symphony]] — see {{bib|1980/112|Stanford, the Cambridge Jubilee, and Tchaikovsky}} (1980), p. 443–444.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note9a">Klein was mistaken here. Tchaikovsky actually stayed in West Lodge, Downing College, [[Cambridge]], as a guest of Professor [[Frederic Maitland]] and his wife. Merton College is in Oxford. We are grateful to Mr Peter Smith for drawing our attention to Klein's error.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note9b">Klein was mistaken here once again, as [[Verdi]] was not included among the recipients, and [[Grieg]] was awarded his honorary doctorate ''in absentia''.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note10">''Don Juan's Serenade'' — No. 1 of the [[Six Romances, Op. 38]].</ref> | |||

</references> | </references> | ||

[[Category:People|Klein, Herman]] | |||

[[Category:Writers|Klein, Herman]] | |||

Revision as of 19:14, 27 December 2022

English music critic, author, and teacher of singing (b. 11/23 July 1856 in Norwich; d. 10 March 1934 in London), also known as Hermann Klein [1].

Biography

Klein began his career as a vocal teacher at the Guildhall School of Music in London. In 1876 he took up musical journalism, writing for The Sunday Times from 1881–1901, and also contributed prolifically to The Musical Times, amongst other publications. In 1901 Klein moved to New York, where he wrote for The New York Herald while continuing to work as a singing tutor. He was one of the first critics to take notice of the gramophone and was appointed "musical adviser" to Columbia Records in 1906 in New York. He returned to England in 1909.

Klein wrote over half a dozen books about music and singers, as well as English translations of operas and art songs. He was a noted authority on Gilbert and Sullivan. In 1924, he began writing for The Gramophone and was in charge of operatic reviews, as well as contributing a monthly article on singing, from then until his death.

Tchaikovsky and Klein

Klein first encounter with Tchaikovsky was at a concert in London on 10/22 March 1888, which he described in his capacity as music critic of The Sunday Times [2]:

M. Tschaikowsky made his first bow — or, rather, the first of several very profound and rapid bows — before an English audience at the Philharmonic Concert on Thursday. A hearty reception awaited him as was fitting in the case of one of the most distinguished of Russian composers [...] M. Tschaikowsky is not quite forty-eight, but he looks older, his hair and close-cut beard being perfectly grey. By his intelligent and animated beat, I should judge him to be a good conductor. It was a pity, though, that he should not have been represented in Thursday's scheme by a work of first-class importance, instead of a Serenade for Strings and a movement of a suite [3], neither of them worthy of this genius in its highest phase. The predominant impression left behind is tinged with a certain coarseness, not to say vulgarity of treatment. M. Tschaikowsky had to respond to two recalls after the Serenade, which brought out the tone of the Philharmonic strings with wonderful sonorousness and purity of quality [4].

When Tchaikovsky returned to England in the summer of 1893 to collect his honorary doctorate of music from Cambridge University, he found himself sharing a railway carriage with Klein on the journey from London to Cambridge. Klein recalled the occasion at length in his memoirs, published ten years later [5]:

In the autumn of 1892 the Russian master's opera "Eugény Onégin" was produced in English at the Olympic Theatre, under the management of Signor Lago, with Eugène Oudin in the title part [6]. It met with poor success, and after a few nights was withdrawn [7].

In the June of 1893, Tschaikowsky came to England to receive the honorary degree of "Mus. Doc." at Cambridge University; the same distinction being simultaneously bestowed upon three other celebrated musicians — Camille Saint-Saëns, Max Bruch, and Arrigo Boïto. By a happy chance I travelled down to Cambridge in the same carriage with Tschaikowsky. I was quite alone in the compartment until the train was actually starting, when the door opened and an elderly gentleman was unceremoniously lifted in, his luggage being bundled in after him by the porters. A glance told me who it was. I offered my assistance, and, after he had recovered his breath, the master told me he recollected that I had been presented to him one night at the Philharmonic. Then followed an hour's delightful conversation.

Tschaikowsky chatted freely about music in Russia. He thought the development of the past twenty-five years had been phenomenal. He attributed it, first, to the intense musical feeling of the people which was now coming to the surface; secondly, to the extraordinary wealth and characteristic beauty of the national melodies or folk-songs; and, thirdly, to the splendid work done by the great teaching institutions at St. Petersburg and Moscow. He spoke particularly of his own Conservatory at Moscow, and begged that if I ever went to that city I would not fail to pay him a visit [8]. He then put some questions about England and inquired especially as to the systems of management and teaching pursued at the Royal Academy and the Royal College. I duly explained, and also gave him some information concerning the Guildhall School of Music and its three thousand students. It surprised him to hear that London possessed such a gigantic musical institution.

"I don't know", he added, "whether to consider England an 'unmusical' nation or not. Sometimes I think one thing, sometimes another. But it is certain that you have audiences for music of every class, and it appears to me probable that before long the larger section of your public will support the best class only". Then the recollection of the failure of his "Eugény Onégin" occurred to him, and he asked me to what I attributed that — the music, the libretto, the performance, or what? I replied, without flattery, that it was certainly not the music. It might have been due in some measure to the lack of dramatic fibre in the story, and in a large degree to the inefficiency of the interpretation and the unsuitability of the locale. "Remember," I went on, "that Pushkin's poem is not known in this country, and that in opera we like a definite dénouement, not an ending where the hero goes out at one door and the heroine at another. As to the performance, the only figure in it that lives distinctly and pleasantly in my memory is Eugène Oudin's superb embodiment of Onégin".

"I have heard a great deal about him", said Tschaikowsky; and then came a first-rate opportunity for me to descant upon the merits of the American barytone. I aroused the master's interest in him to such good purpose that he promised not to leave England without making his acquaintance, — "and hearing him sing?" I queried. "Not only will I hear him sing, but invite him to come to Russia and ask him to sing some of my songs there", was the composer's reply as the train drew up at Cambridge, and we alighted [9]. Tschaikowsky was to be the guest of the Master of Merton [10], and I undertook to see him safely bestowed at the college before proceeding to my hotel. Telling the flyman to take a slightly circuitous route, I pointed out various places of interest as we passed them, and Tschaikowsky seemed thoroughly to enjoy the drive. When we parted at the college, he shook me warmly by the hand and expressed a hope that when he next visited England he might see more of me. Unhappily, that kindly wish was never to be fulfilled.

The group of new "Mus. Docs." was to have included Verdi and Grieg [11], but these composers were unable to accept the invitation of the University. However, the remaining four constituted a sufficiently illustrious group, and the concert at the Cambridge Guildhall was of memorable interest. Saint-Saëns played for the first time the brilliant pianoforte fantasia "Africa", which he had lately written at Cairo; Max Bruch directed a choral scene from his "Odysseus"; and Boïto conducted

the prologue from "Mefistofele", Georg Henschel singing the solo part. Finally, Tschaikowsky directed the first performance in England of his fine symphonic poem, "Francesca da Rimini", a work depicting with graphic power the tormenting winds wherein Dante beholds Francesca in the "Second Circle" and hears her recital of her sad story, as described in the fifth canto of the

"Inferno". The ovation that greeted each master in turn will be readily imagined. A night or two later I met Boïto at a reception given in his honour by my friend Albert Visetti, and the renowned librettist-composer did me the pleasure of accompanying me to the last Philharmonic concert of the season, at which Max Bruch conducted a couple of works and Paderewski played his concerto in A minor.

Tschaikowsky and Eugène Oudin duly met. The latter sang the "Serenade de Don Juan" [12] and other songs of the Russian master, and so delighted him that the visit to St. Petersburg and Moscow was immediately arranged.

Bibliography

- Music and Musicians (1888)

- Personal recollections of Tschaikowsky (1903)

- Thirty years of musical life in London, 1870-1900 (1903)

- Thirty years of musical life in London, 1870-1900 (1903)

- Встреча с Чайковским (1973)

- Thirty years of musical life in London, 1870-1900 (1978)

- Встреча с Чайковским (1979)

- Встреча с Чайковским (1980)

- Herman Klein (1993)

- Eine Begegnung mit Tschaikowsky in England (1994)

- Herman Klein (1999)

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ In his 1903 autobiography Thirty years of musical life in London, 1870-1900 (1903) his name was spelled as "Hermann Klein", but government records of his birth and death confirm that "Herman" was his official forename.

- ↑ See Music and Musicians (1888).

- ↑ The Theme and Variations from the Suite No. 3.

- ↑ Extracts quoted in Tchaikovsky through others' eyes (1999), p. 157.

- ↑ Thirty years of musical life in London, 1870-1900 (1903), p. 343-350.

- ↑ The premiere took place on 5/17 October 1892 at the Olympic Theatre, with a cast including Madame Selma (Larina), Fanny Moody (Tatyana), Lily Moody (Olga), Aleksandra Svyatlovskaya (Filippyevna), Eugène Oudin (Onegin), Iver McKay (Lensky), and Charles Manners (Gremin), conducted by Henry Wood.

- ↑ "The whole undertaking was ill-timed and ill-placed" — Klein's footnote.

- ↑ "I did visit Moscow in the summer of 1898, and, on presenting my card as an English friend of the lamented master, was received by the Conservatory officials with every attention and cordiality" — Klein's footnote.

- ↑ Gerald Norris, however, has pointed out that in the earliest description of this conversation published by Klein (in the Sunday Times of 12 November 1893 [N.S.]), Tchaikovsky's words are reported slightly differently: "I have heard Oudin, and I am sure he at least must have been excellent" [as Onegin]. This would suggest that Tchaikovsky had already made the acquaintance of Oudin and even heard him sing. In fact, as Norris argues, the composer had almost certainly attended Eugène and Louise Oudin's afternoon recital in Saint James's Hall, London, on 20 May/1 June 1893, a few hours before he himself conducted, in the same venue, the first performance in England of his Fourth Symphony — see Stanford, the Cambridge Jubilee, and Tchaikovsky (1980), p. 443–444.

- ↑ Klein was mistaken here. Tchaikovsky actually stayed in West Lodge, Downing College, Cambridge, as a guest of Professor Frederic Maitland and his wife. Merton College is in Oxford. We are grateful to Mr Peter Smith for drawing our attention to Klein's error.

- ↑ Klein was mistaken here once again, as Verdi was not included among the recipients, and Grieg was awarded his honorary doctorate in absentia.

- ↑ Don Juan's Serenade — No. 1 of the Six Romances, Op. 38.