Letter 1396

| Date | 4/16 January 1880 |

|---|---|

| Addressed to | Sergey Taneyev |

| Where written | Rome |

| Language | Russian |

| Autograph Location | Moscow: Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (ф. 880) |

| Publication | Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 2 (1901), p. 360–362 (abridged) Письма П. И. Чайковского и С. И. Танеева (1874-1893) [1916], p. 41–43 (abridged) П. И. Чайковский. С. И. Танеев. Письма (1951), p. 46–48 П. И. Чайковский. Полное собрание сочинений, том IX (1965), p. 14–16 |

| Notes | Autograph date erroneously written as "1888" |

Text and Translation

| Russian text (original) |

English translation By Luis Sundkvist |

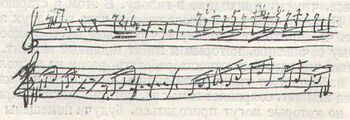

Получил Ваше письмо, милый Серёжа, и несказанно Вам за него благодарен. Напрасно Вы усмотрели где-то в моих выражениях «язвительность». Я никогда и не думал обижаться на то, что Вы не пишете мне. По себе знаю, как противно писать, когда есть дело, а у Вас, я знаю, праздных минут не много. Я только иногда грущу, не имея долго никаких известий из Москвы, и мне неприятно бывает подолгу терять Вас из виду. Если Вы будете хотя кратко, но изредка мне рапортовать о Вашем житье-бытье, то это всё, что мне нужно. Объяснения Ник[олая] Гр[игорьевича] нимало не удовлетворили меня. По всему вижу, что, как это иногда бывает с ним, на него нашло дурное расположение духа и обрушилось на сюиту. Никто в мире не докажет мне, что будто бы гобою и кларнету трудно сыграть: или что флейты не могут 22 такта сряду делать триолеты в скором темпе. Да они без всякого труда 200 тактов могут валять подобные пассажи! Очень наивно было бы думать, что это должно делаться без передышки. Передышкам место есть; я сам на флейте чуточку играю и говорю это с полным убеждением. Трудность—понятие относительное; для ученика 1-го года консерват[орского] курса это не только трудно, но невозможно, а для обыкновенного хорошего оркестрового музыканта это не трудно. Впрочем, я далёк от претензии уметь писать легко; я знаю, что все мои инструментовки всегда страдали относительной трудностью, но согласитесь, Сергей Иванович, что сюита есть сущая игрушка в сравнении с «Франческой», даже с 4-ой симфонией, по поводу которых Ник[олай] Григ[орьевич] и не думал жаловаться на особенную трудность. Вообще все замечания Ник[олая] Григ[орьевича] таковы, что если бы они были основательны, то мне положительно следует отказаться писать. Как! Десять лет сряду я преподавал в его Консерватории инструментовку (положим, неважно, однако ж так, что не особенно компрометировал себя), и после этого ещё через 2 года мне делают такие замечания, какие может заслужить только плохой ученик? Что-нибудь одно: или я никогда ни бельмеса не смыслил в оркестре, или критика моей сюиты составляет pendant к положительному заявлению Ник[олая] Григ[орьевича], сделанному в 1875 г., о концерте, что будто бы его невозможно играть. Однако ж то, что было невозможно в 1875, сделалось совершенно возможным в 1878-м. Впрочем, у меня есть ещё одно объяснение. Г. Медер был не в духе, что с ним бывает, и это отозвалось на Ник[олае] Григ[орьевиче]. Мне очень нравится, что высокие ноты портят г. Медеру губы!!! Очень жаль, что эти драгоценные губки, с которых г-жа Медер срывала так много поцелуев, навеки пострадали от того, что ему пришлось сыграть 2-х-чертное mi. Однако ж это не помешает мне и впредь, если окажется нужным, портить священные медеровские губы высокими нотами, которые всякий другой гобоист и без всякого особенного французского мундштука играет совершенно свободно. Но довольно об несчастной сюите. Можете не говорить Ник[олаю] Григ[орьевичу] о моём ответе на его замечания. Так как в конце концов она была исполнена хорошо, то мне остаётся только быть ему благодарным, а ведь разубедить его было бы тщетной попыткой. Меня нисколько не удивит, если через три года он поставит эту же сюиту как пример лёгкости. Теперь скажу Вам кое-что о себе. Во-первых, у меня сегодня болят зубы; я, может быть, от этого выразился довольно резко о критике Ник[олая] Григ[орьевича]. Вообще же, я пользуюсь вожделенным здравием. Рим не совсем подходящее для меня местопребывание. Он слишком шумен, слишком роскошен историческими и художественными богатствами, в нём нельзя жить тихо и незаметно в своей норке; беспрестанно приходится выползать, и я даже не мог здесь скрыть своего инкогнито. Нашлись господа и госпожи, усиленно навязывавшиеся ко мне на знакомство. Тем не менее провожу время хорошо благодаря обществу брата Модеста. Климат удивительный. Занятия мои следующие:

Всё это уже почти совсем готово. Теперь представляется вопрос: как выручить эту несчастную симфонию от Бесселя? Он 7 лет сряду надувал меня, уверял, что партитура печатается. Положим, благодаря его обману я мог теперь переделать вновь симфонию; но кто мне поручится, что он напечатает в новом виде 4-ручное переложение, а также партитуру и голоса? Я написал ему письмо, ответ на которое ещё не получил. Но сделаю всё возможное, чтобы вырвать её из рук его. Передайте от меня самую тёплую благодарность Варваре Павловне, а также Масловым за их милые приписки. Как мне захотелось, читая их, очутиться на несколько часов в их милом обществе, с Вами и с матушкой Вашей! Буду с величайшим нетерпением ожидать Вашего трио. Я останусь здесь ещё несколько времени; если перееду, то адрес мой будет у Юргенсона. Хочу написать итальянскую сюиту из народных мелодий. Обнимаю Вас. Ваш П. Чайковский Скажите Варваре Ивановне, что советом её насчёт слов Фета непременно воспользуюсь. В Селище когда-нибудь побываю, и радуюсь, что там есть опёнки. |

I've received your letter, dear Serezha, and I am unspeakably grateful to you for it. You were wrong to see sarcasm in any of my words [2]. It has never so much as crossed my mind to take offence at your not writing to me. I know from my own experience how loathsome it is to have to write when one has work to do, and, as I am well aware, you don't have many moments of leisure. I only become sad sometimes when I haven't had any news from Moscow for a while, and it is unpleasant for me to lose sight of you for long. If you were to report to me every now and then, even if only briefly, on your life, that would be all I ask for. Nikolay Grigoryevich's explanations have not satisfied me in the least. I can see from everything that, as is sometimes the case with him, he happened to be in a bad mood and took it out on the suite [3]. No one on earth is going to convince me that for the oboe and clarinet it is difficult to play: or that the flutes cannot perform twenty-two bars of continuous triplets at a fast tempo. Why, they can pull off 200 bars of such passages without any difficulty whatsoever! It would be very naive to imagine that this has to be done without any breathing-spaces. There is room for breathing-spaces: I play the flute a little myself [4], and I say this with utter conviction. Difficulty is a relative concept. For a first-year Conservatory student this would be not only difficult but impossible, whereas for a normal good orchestra player it is not difficult. However, I am far from presuming that I know how to write lightly [for the orchestra]. I know that all my orchestrations have always suffered from being relatively difficult, but surely you would agree, Sergey Ivanovich, that the suite is a mere plaything when compared to Francesca, or even to the 4th Symphony, with regard to which it did not even occur to Nikolay Grigoryevich to complain about any particular difficulties. In general, all of Nikolay Grigoryevich's criticisms are of such a kind that, if they were indeed well founded, I would really have to abstain from writing any more music. What! For ten years running I taught orchestration at his Conservatory (granted, not too well, but even so without making myself ridiculous), and even two years later I get to hear the kind of criticisms which only a mediocre student would deserve?! One of the two: either I have never had a clue about the orchestra, or this critique of my suite is on a par with the categorical assertion which Nikolay Grigoryevich made about my concerto in 1875, when he claimed that it was impossible to play. And yet, what was impossible in 1875 has become completely possible in 1878 [5]. However, I can think of one other explanation. Mr Meder was in low spirits, as often happens to him, and this rubbed off on Nikolay Grigoryevich. I really do like this detail about the high notes spoiling Mr Meder's lips!!! I'm awfully sorry that these precious lips, from which Mrs Meder has snatched so many kisses, have been damaged forever by his having to play a double-lined E. However, this will not stop me from continuing to ruin Mr Meder's sacred lips in future, if it should prove necessary, with high notes which any other oboist would be able to play quite easily, even without a special French mouthpiece [6]. However, enough of the unhappy suite. You don't have to tell Nikolay Grigoryevich about my response to his criticisms. Since it was in the end performed well, I cannot but be grateful to him, and, besides, it would be quite in vain to attempt to make him change his mind. It wouldn't surprise me if in three years' time he starts citing this very suite as a model of easy writing for the orchestra. Now I shall tell you one or two things about myself. First of all, I've got toothache today, and it is perhaps because of this that I have spoken in such sharp terms about Nikolay Grigoryevich's criticisms. On the whole, though, I am enjoying perfect health. Rome is not quite suitable as a place of residence for me. It is far too noisy a city, far too luxuriously endowed with historical and artistic riches; it is impossible to live quietly here and to remain unnoticed in my own little burrow: I am constantly having to creep out of it, and I was not even able to preserve my incognito. Gentlemen and ladies have turned up who thrust themselves upon me, seeking my acquaintance [7]. Nevertheless, I am spending my time agreeably thanks to the company of my brother Modest. The climate is astonishing. My work consists of the following:

All this is almost completely ready. Now the question is: how can I rescue this unfortunate symphony from Bessel? For seven years running, he has been deceiving me and assuring me that the score was being printed [8]. Granted, it is thanks to his deceit that I have now been able to revise the symphony, but who can guarantee that he will print the piano duet arrangement of the new version, as well as the full score and parts? I have written him a letter, to which I have not had any reply yet. However, I shall do everything possible to wrest it from his clutches. Please convey my most cordial gratitude to Varvara Pavlovna, as well as to the Maslovs for their sweet postscripts. While reading them, I wished so much that I could find myself for a few hours in their dear company, with you and your dear little mother! I shall be awaiting your trio with the greatest impatience [9]. I shall stay here for a while yet. If I go somewhere else, then you can obtain my address from Jurgenson. I want to write an Italian suite on folk melodies [10]. I embrace you. Yours, P. Tchaikovsky Tell Varvara Ivanovna that I shall without fail make use of her advice regarding those verses by Fet. I shall come to Selishche someday, and I am glad that they have honey agarics [11] over there. |

Notes and References

- ↑ The incorrect year was a slip of the pen by Tchaikovsky.

- ↑ In his earlier letter to Taneyev of 19/31 December 1879 (Letter 1383), Tchaikovsky had written: "Would you be so kind as to ask Nikolay Grigoryevich where the suite's particular difficulty lies in his view, and then to write to me about this, only about this: it will take you no more than a quarter of an hour". Taneyev had interpreted this as an ironic allusion to his indolence with regard to letter-writing, and he opened his reply to Tchaikovsky on 28 December 1879/9 January 1880, in which he summarized Nikolay Rubinstein's reservations about the recently premiered Suite No. 1, as follows: "I have just received your letter, my dear Pyotr Ilyich, and I hasten to reply to it. I fully deserved those lines in which you somewhat sarcastically asked me to write only about your request, and about nothing else. I acknowledge that I deserve this; all the same I am grateful to you for your letter". Taneyev's letter has been published in П. И. Чайковский. С. И. Танеев. Письма (1951), p. 42–46.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky's Suite No. 1 had been given its first performance at a Russian Musical Society concert in Moscow on 8/20 December 1879, conducted by Nikolay Rubinstein. The composer had found out from a letter from his publisher Jurgenson that Rubinstein had described the suite as almost impossible to perform because of the demands it made on the orchestra players. Tchaikovsky had then written to Taneyev on 19/31 December 1879 (Letter 1383), asking him to speak to Rubinstein and clarify what exactly was so difficult about his suite. In his reply of 28 December 1879/9 January 1880, Taneyev set out in detail the problems which Rubinstein and some of the orchestra players (particularly from the woodwind section) had encountered during rehearsals and at the concert itself.

- ↑ During his student years at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, Tchaikovsky had taken flute lessons with the distinguished Italian flautist Cesare Ciardi (1817–1877), who had settled in Russia in 1853 and played in the Italian Opera company's orchestra in the Imperial capital, as well as teaching at the Conservatory. Tchaikovsky always retained a keen interest in this instrument: for example, for the Chinese Dance in The Nutcracker he made use of a special effect which he picked up from the Kiev-based flautist Aleksandr Khimichenko, and in the last year of his life he was considering writing a Flute Concerto for the French virtuoso Claude Paul Taffanel.

- ↑ Nikolay Rubinstein, who had been so critical about Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1 when the composer showed it to him on Christmas Eve in 1874, drastically changed his mind about the work subsequently and performed it to great acclaim at the Russian Concerts during the International Exposition in Paris in the summer of 1878.

- ↑ In his letter of 28 December 1879/9 January 1880, Taneyev had explained that at the first rehearsal of the Suite No. 1, the oboist Eduard Karlovich Meder had not played a certain passage as it was written in the score: "When Nikolay Grigoryevich asked why he wasn't playing as it was written, Meder replied that he could play it, but that it damaged his lips because it was far too high; that French oboists could play such notes, but that they have other mouthpieces which are thinner and capable of producing high sounds; that he could change to such a mouthpiece, but that then the low and middle notes would suffer because they come out worse with such a mouthpiece".

- ↑ Tchaikovsky is referring partly to the local artistic, bohemian and homosexual circles in Rome into which he was introduced by his Russian friends, Prince Aleksey Golitsyn (1832–1901) and Nikolay Masalitinov (d. 1884), who were staying in the Eternal City at the time. For more details on the composer's stay in Rome that winter, see Tchaikovsky. The quest for the inner man (1993), p. 358–359, and Пётр Чайковский. Биография, том II (2009), p. 92–99.

- ↑ |The Saint Petersburg-based publisher Vasily Bessel had brought out Tchaikovsky's own piano duet arrangement of the Symphony No. 2 (original version) in 1873, but he kept procrastinating over the printing of the full score. Despite Tchaikovsky's misgivings about this publisher, Bessel would publish the piano duet arrangement, full score and parts of the revised version of the symphony in 1881.

- ↑ In his letter of 28 December 1879/9 January 1880, Taneyev wrote that he was composing a String Trio (in D major, for violin, viola and cello) which he hoped to finish by the New Year, after which he intended to ask some of his colleagues at the Conservatory to play it and then to send the score to Tchaikovsky, whom he asked to look over the manuscript and write his comments on it. After completing his trio, however, Taneyev decided not to send the score to Tchaikovsky abroad, but showed it to him later that spring when they met in Moscow. On the last page of the score, Tchaikovsky made the following note: "I looked through [this] and was greatly amazed by the author's artistry. P. Tchaikovsky. 10 April 1880. Moscow". See Sergey Popov's article «Неизданные сочинения и работы С. И. Танеева» (Unpublished compositions and works by S. I. Taneyev) in Сергей Иванович Танеев: Личность, творчество и документы его жизни (Moscow; Leningrad, 1925), p. 131.

- ↑ This is the earliest reference to what would become the Italian Capriccio.

- ↑ A type of mushroom.