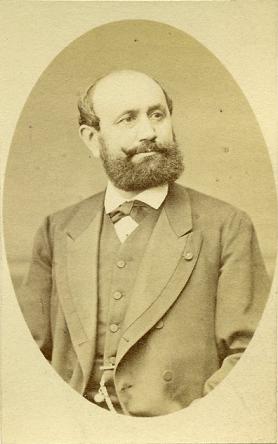

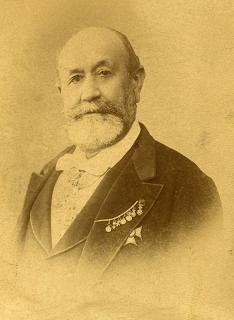

Léonce Détroyat

French naval officer, politician, journalist and librettist (b. 7 September 1829 [N.S.] in Bayonne; d. 18 January 1898 [N.S.] in Paris), born Pierre Léonce Détroyat.

Early Years

Pierre Léonce Détroyat was born on 7 September 1829 in Bayonne, at No. 26 Rue du Bourgneuf. His father, Jean Théodore, had also been born in Bayonne, on 8 November 1799. The elder Détroyat worked as a saddler before becoming a mail guard. He served in the city council of Bayonne and would eventually be appointed president of the chamber of commerce there.

The Détroyat family was originally from Chatte, in the historical region of France known as the Dauphiné. After spending some years in Valence, Pierre Détroyat, the namesake and ancestor of our main subject, had emigrated to Bayonne in 1774. His numerous descendants would make a significant contribution to the city's life over almost a century, distinguishing themselves in particular in the fields of banking and commerce, as well as in military careers. Some of them became prominent members of the local Masonic lodge, the so-called "Zélée".

Léonce's mother, Marie Julie Passement, was born in Bayonne into a family of modest means. Her own parents were originally from the Comminges and Toulouse regions of southern France. Her father, a simple tailor, had established himself in one of the poorer neighbourhoods of the city, whereas the Détroyat family lived on the opposite bank of the river Nive — in those times living on this or that bank of the river was a mark of one's social status. Léonce's parents had therefore at first to contend with some hostility on the part of the Détroyat family, but this would abate when their children were born: two boys, Léonce and Henri, and two daughters, Caroline and Camille.

Léonce went to school in the town of Pons, in the Charente Maritime department. He then studied at the Collège d'Aumale in Lorient, Brittany, in order to prepare for the entrance examinations to the École Navale in Brest. He enrolled in the academy on 4 October 1845, and two years later qualified from the training ship Le Borda with the rank of midshipman, 2nd class.

Military Campaigns

Détroyat's file in the French Navy archives [1] shows that from 1847 to 1862 he was embarked on a number of vessels, first on sailing ships, then paddle-steamers, and finally screw-powered frigates, reflecting the development of the country's war fleet over these years. His file also records that he was stationed on land on a few occasions, at Lorient and above all at Toulon.

During a military career that spanned twenty-one years Détroyat took part in three campaigns: the Crimean War, the capture of Tourane in Annam, and the French Mexican Expedition.

His military record does not give any specific details about the actions he was involved in during the Crimean War [2]. However, it must undoubtedly have been on board the paddle-driven corvette Tanger that he took part in the allied offensive. He was decorated with the Victoria Cross on that occasion.

The campaign in China and Indo-China was his first important expedition [3]. He described it in detail in the numerous letters that he wrote to his mother and to his brother, Henri.

On 4 March 1858, Détroyat, by then a midshipman, left Brest on board the Saône, an old screw-propelled boat which carried 600 troops and 22 officers. He shared a cramped gun battery with five other midshipmen, having to sleep on a hammock. After stopovers in Tenerife, Île Gorée, and Capetown, the ship arrived at Île Bourbon (now Réunion), where Détroyat was received by the Dousdebès family, cousins of his from Bayonne who had settled on the island. Passing through the Strait of Malacca, the ship made its way to Singapur and then Hong Kong. It was in the South China Sea, near the island of Hai-Nan, that the French expeditionary force joined up with the Spanish fleet which had come from the Philippines.

On 5 September, Détroyat was in charge of a gun battery on board the corvette Primauguet in the Bay of Tourane, and he took part in the series of engagements that ended with the capture of the port. His description of the siege in the letters that he sent home shows how savage the fighting on both sides was. After being injured by a lance during the capture of the Don-nai fort, he was mentioned in a despatch. Having distinguished himself in various engagements, he was eventually made a Knight of the Légion d'honneur, and also received the Laureate Cross of the Order of Saint Ferdinand of Spain, a decoration which was only awarded for gallantry on the battlefield. In the course of this campaign he frequently found himself serving under Commander Jauréguiberry, fourteen years his senior and like him a native of Bayonne.

In January 1860, he was put in command of the merchant ship L'Asce which was given the task of bringing injured and convalescent soldiers back to France. Upon his return, he was promoted to the rank of sub-lieutenant on 11 July 1860 and subsequently served on various ships, as well as completing a turn of duty on land at the port of Toulon.

Shortly afterwards Détroyat found himself involved in the Mexican campaign [4]. On 10 July 1862, he was put at the disposal of the vice-admiral who had overall command over the naval forces in the Gulf of Mexico. He served first on a stationnaire ship off the port of Veracruz before taking part in various engagements on land, in particular the march on Xalapa and the fighting around the besieged city of Puebla in May 1863. After entering Mexico City he was seconded as a staff officer to Generals Berthier and Douay, and later to the staff headquarters of General Bazaine. On 20 February 1864, he was mentioned in the order of the day by the commander-in-chief for his gallant conduct during the capture of the fort of Tocatische, and he was made an Officer of the Légion d'honneur.

On 28 May 1864, Emperor Maximilian landed at the port of Veracruz and made his way to Mexico City. When he appointed his cabinet, his decision to include Détroyat in it was probably due to the fact that this officer could speak Spanish fluently, and also had some knowledge of German. On 25 November, by order of the Emperor, he was detached to the Mexican Ministry of War by Marshal Bazaine, specifically as Secretary of State for the Navy. Moreover, in March 1866 Maximilian appointed him his private secretary and entrusted him with the "Overall direction of Military Affairs". Détroyat was thus in very close contact with Maximilian, and he also had the opportunity to take part in the brilliant court life at Chapultepec Castle. Nevertheless, his situation proved to be rather difficult since he was supposed to act as an intermediary between the Emperor and Marshal Bazaine, who was sending dispatches to Paris full of an optimism that by no means reflected the true state of affairs.

Once the American Civil War had come to an end, the US government began to make threatening gestures, and Détroyat realised very soon that Napoleon III would be seeking to withdraw from the Mexican hornet's nest. He tried to open Maximilian's eyes to this. Marshal Bazaine took offence, and, on 22 March 1866, he demanded that Détroyat be made to resume his duties in the French Navy, claiming that his ministerial role had been "quite unproductive", as well as pointing to "the circulation of rumours about all kinds of palace intrigues, against which the French uniform of this detached officer does not afford him more protection than is the case with many others". Might this be an allusion, as some have suggested, to a secret liaison with Empress Charlotte?[5] On 7 May, Détroyat received orders to resume his naval service. Conscious as he was of the military and political situation, he implored the Emperor to abdicate. Maximilian refused, but asked Détroyat to accompany Empress Charlotte to Europe. On 1 July, they left Mexico City, and on the 10th they boarded the steamship L'Impératrice Eugénie [6]. A month later, they went ashore at Saint-Nazaire and made their way to Paris. Empress Charlotte attempted to enlist the support of Napoleon III for the Mexican Empire, but, disillusioned by the frosty reception she was accorded, she returned to her native Belgium shortly afterwards. She would gradually lose her reason as she found out about the tragic course that events in Mexico had taken.

In Paris, Détroyat was supposed to report to the Directorate of Fleet Operations. At his meetings with officials there he took the opportunity to denounce the peculiar methods of Marshal Bazaine at the French headquarters in Mexico. No one believed him, and, having fallen into suspicion, he was forbidden from returning to Mexico. At his own request he was allowed to go to Bayonne on half-pay for three months in order to attend to some personal matters. In December 1866, he was attached to the Navy's storehouse of maps and documents and ordered by the Minister of the Navy to write some reports on the Franco-Mexican War. He was granted leave as an officer in non-activity in March 1867 and retired from the Navy the following month.

From Marriage to Journalism

On 20 December 1866, three months after his return to France, Détroyat was married to Hélène Louise Garre at the Church of the Madeleine in Paris. He was 38 years old, and both his parents were dead. It was undoubtedly in the salon of Émile Girardin that he met Hélène, who was a strikingly beautiful young woman of 24 at the time of their marriage. She had until then lived with her mother at No. 9, Rue de Richepanse, where she led a rather secluded life. Her father, Louis Garre, had died in 1862. Her mother, Isaure, gave English lessons. Isaure was the youngest daughter of Sophie Gay, a female writer famous for her salon which during the Empire and the Restoration was frequented by all the literary, artistic, and political celebrities of the age. Isaure's modesty was in stark contrast with the stir made by her sister, Delphine Gay, who achieved fame for her literary talents, as well as for the salon which she hosted, and which was in no way inferior to that of her mother. In 1831, Delphine had married the future press baron, Émile de Girardin. This marriage did not produce any children. After his wife's death in June 1855, Émile remained close to his sister-in-law Isaure, and, in particular, to his niece Hélène, for whom he always showed great affection. He was one of the guests present at her marriage with Léonce Détroyat, and was later godfather to their son, Maurice, my grandfather.

Détroyat's marriage to Hélène Garre would determine the future course of his life. Having thereby become the nephew of Émile de Girardin, he would turn to journalism and was spared the difficult first steps into this career. He made his début in La Liberté, a liberal newspaper that came into being during the Second Empire, using the pseudonym L. de Bourgneuf. His articles showed him to be a journalist full of verve and élan, and they soon attracted the attention of the public, particularly those in which he wrote about the Spanish question and the reorganization of the Army. On 31 May 1870, Girardin handed La Liberté over to him, and he would direct this newspaper until 1876.

His courteous but fiery manner of debate caused sparks to fly. One of his first opponents was Rochefort, whom he had attacked, and who in turn fired this witty barb at him: "This morning I read an article attacking me signed: Détroyat. What does this third person of the imperfect subjunctive of the verb Détroyer have against me?"[7]

In almost no time at all he had carved a very enviable niche for himself in the world of Parisian journalism. However, this adventurous spirit did not like staying still in the same place for too long.

When war with Germany came in 1870 [8], Détroyat initially remained in Paris. Soon after the establishment of the Commune on 18 March 1871, warrants of arrest were drawn up which included the names of most chief editors of newspapers. Émile de Girardin and Détroyat were sentenced to death, but managed to escape from Paris and reach Versailles. Détroyat then made his way to Bordeaux where he had already transferred his newspaper La Liberté after its suppression by the Commune, entrusting the directorship to M. G. Ganesco soon afterwards.

Wishing to play an active role in the events, Détroyat had earlier contacted Gambetta, who asked him to co-ordinate the correspondence coming in from the army generals in the provinces in the capacity of "General Secretary of the National Defence". Détroyat had declined that offer, but, on 6 December, he did accept an appointment as commander of the camp at La Rochelle, with the rank of an auxiliary Division General, and he would remain in command of that camp until the armistice. He became eligible for retirement on 11 October 1870, twenty-five years since he had first entered military service.

Whilst Bismarck was happy to conclude an armistice with the de facto administration, namely that of Gambetta (Napoleon III had not yet formally abdicated), he stipulated as a condition for signing the peace treaty that there should be a government constituted by means of free elections. These took place on 8 February 1871 under the gaze of the victors. Bismarck had in fact vetoed certain candidates, including Détroyat, who had presented himself for election in the département of Indre-et-Loire. A supporter of 'war to the death', he was forced to leave Tours in great haste as the Prussian military authorities had decided to persecute him.

Once peace was restored he took up his pen again and would contribute to the defeat of the attempt, in 1871, to re-install the monarchy in France. He bravely supported the Bonapartist Appel au peuple group. In 1877, he presented himself for election in Neuilly-sur-Seine but was defeated by the incumbent candidate.

He continued to direct La Liberté until 1876, after which he set up and directed several other publications, including Le Bon Sens which would soon merge with L'Estafette, Détroyat becoming the chief editor. He turned this into a dynamic newspaper which soon made its mark in the Parisian press thanks to the swiftness of its news reporting. In 1885, he was fleetingly director of Le Constitutionnel but still managed to turn it into a republican newspaper during his tenure. Finally, he set up in Madrid the newspaper Europa which, however, turned out to be very short-lived. He wrote a pamphlet about the Senate and also one about the procedure for electing deputies to the National Assembly.

Moreover, in these years, conscious that he had loved music all his life, he became friends with some of the great musicians and composers of the age: Gounod, Messager, Godard, Théodore Dubois, Camille Saint-Saëns... He corresponded with Tchaikovsky [9], Offenbach, Meyerbeer...

He also became a librettist. Thus, in collaboration with Armand Silvestre he wrote the libretto for Henri VIII. He offered it first to Gounod, who rejected it, and then to Saint-Saëns, who accepted it: this opera is to this day still performed in many opera-houses around the world. Then came Pedro de Zalamea, by Godard, for which he wrote the libretto in collaboration with M. de Lauzières. For the libretto of Théodore Dubois's Aben-Hamet he was the sole author.

When the Salle Drouot burnt down, Paris was left without a lyric stage. Together with many other opera enthusiasts, Détroyat wanted to set up a new lyric theatre. The project was announced in a series of articles, but still failed to get off the ground. For a number of months Détroyat was director of the Théâtre de la Renaissance, where he staged Messager's Madame Chrysanthème.

He wrote one comedy for the theatre: Entre l'enclume et le marteau (Between the anvil and the hammer). He published several works, including: La cour de Rome et l'Empereur Maximilien (1868), L'intervention française au Mexique (1868), Du recrutement, de l'organisation et de l'instruction de l'armée française (1870), La liberté de l'enseignement et les projets de Jules Ferry (1879), Le secret et scrutin de liste (1881), La France en Indochine (1887), Les chemins de fer en Amérique (1886).

In his last years, he fell into obscurity and suffered from ill health. This man, whose life had been so ardent and eventful, could now be seen trudging sadly along the streets near the Opéra. He seemed like a ghost from a former age. Moreover, after some financial speculations which had not all turned out well, he found himself deprived of much of his fortune [10]

Death

Léonce Détroyat died on 18 January 1898 at his house on the Rue d'Isly in Paris, of the consequences of an apoplexy suffered a few weeks earlier. He was 68 years old. The funeral service was held at the church of Saint-Louis d'Antin. The cortège was led by his son Maurice and his brother Henri. Among other family members it is worth singling out Ramon Del Valle, who had married the deceased's sister, Caroline [11]. Numerous friends and colleagues from the staff of several newspapers were in attendance. An infantry company paid him military honours. He was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery [12].

All the newspapers of Paris, and many provincial ones too, reported his death and published more or less extensive obituaries. Some colleagues added kind personal remarks: "a very widely and well known Parisian who was appreciated for his intelligence and energy. He was loved for his kindness and courtesy."

Jacques Rigaud of Le Figaro gave a quite perceptive, though unkind, portrait of him:

Few lives can have been as eventful as that of Léonce Détroyat. He laid his finger on many things, even if in these his capacities and merits never exceeded a good honest average level. At any rate he showed a most rare facility for assimilation, and at the same time a flexibility of mind that really do cause one to lament that, instead of wearing himself out in multiple enterprises, he was not fated to pursue one single goal and to devote himself entirely to that.

After serving brilliantly as a naval officer one would have thought that a career which had begun so well must surely have taken him to the highest ranks. His voluntary resignation stopped him on that brilliant path. He tendered this resignation in order to become a journalist and to succeed Girardin as director of La Liberté. It is in this capacity that the whole of Paris saw him during nine years deploy the qualities which were characteristic of him — superficial qualities perhaps, but expended with such warmth, such bustle, such good humour, and such eloquence that they led others to imagine him to be an exceptional man, when in fact he was above all a restless one.

He was a Southerner from Gascony, sufficienty endowed with that gift of assimilation which led one to believe that he possessed all those qualities that he lacked. A journalist, a general during the war, the organizer and commander of the camp at La Rochelle where one could see Girardin among his general staff, director of La Liberté, of L'Estafette, of Le Constitutionnel, of the Madrid-based newspaper Europa, a businessman, the author of operatic librettos, someone who touched upon all matters, who got himself involved in all the incidents of public life, who embarked on all these diverse careers — he threw himself into all these enterprises always with the same enthusiasm. He was a man of sudden flashes of inspiration. His mobility was proverbial. When the war broke out, he took his newspaper La Liberté to Bordeaux. After the newspaper had barely been launched he handed over the reins to Ganesco, went to Tours, asked to be appointed a commander, set himself up as a general, and, after the peace was signed, returned to being a journalist.

At Versailles he gave some pieces of advice to M. Thiers, who, incidentally, did not follow them; he proposed various political coalitions to the deputies; in 1873, he blocked the attempts to achieve a restoration of the monarchy and for a moment seemed poised to occupy a high office of state.

To everything in which he was involved he brought, under the mask of a brutal scepticism, a naivety and candour testifying to a rare goodness of heart, and a frustrating lack of perseverance; on the other hand, he was incapable of hating those of whom he had cause to complain, or of taking revenge.

In his praise we can say that his mobility left no other victims than himself. From the day that he gave up La Liberté he was condemned to lead a vegetating existence. The last years of his life would have been very sorrowful if his wife had not been the noblest, the most patient and most courageous of women, and if he had not had cause to be happy and proud of the son she had given him [13].

Thus vanished from the face of this earth Léonce, the most illustrious of the Détroyats in the nineteenth century, who, by the peculiar accident of his marriage, left the sea for the storms of Parisian journalism. He could not guess that in the following century a cousin of his, Michel Détroyat (1905–1956) would attain celebrity as the 'acrobat of the skies' [14].

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

9 letters from Tchaikovsky to Léonce Détroyat have survived, dating from 1888 to 1890, and have been translated into English on this website:

- Letter 3563b – 10/22 May 1888, from Frolovskoye

- Letter 3581a – 30 May/11 June 1888, from Frolovskoye

- Letter 3590a – 13/25 June 1888, from Frolovskoye

- Letter 3598a – 20 June/2 July 1888, from Frolovskoye

- Letter 3712a – 28 October/9 November 1888, from Frolovskoye

- Letter 3827a – 23 March/4 April 1889, from Paris

- Letter 3905a – 17/29 July 1889, from Frolovskoye

- Letter 4214a – 9/21 September 1890, from Tiflis

- Letter 4225a – 3/15 October 1890, from Tiflis

15 letters from Détroyat to the composer, dating from 1888 to 1891, are preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin (a4, Nos. 948–962).

Bibliography

- Paris vaut bien une messe! Bisher unbekannte Briefe, Notenautographie und andere Čajkovskij-Funde (1998)

- Szenarium zu Čajkovskijs Opernprojekt Sadia (La Courtisane) (2014)

- Čajkovskijs Opernprojekt Sadia (La Courtisane) (2014)

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ Ref. Bro 140: biographical notice written by D. Lemaire, maître principal.

- ↑ Historical note: Tsar Nicholas I wanted to take advantage of the weakness of the Ottoman Empire in order to gain control over the Dardanelles and thereby secure access to the Mediterranean — something that was unacceptable for England. Moreover, he provoked France which wished to act as the sole protector of Christians within the Turkish territories. War broke out on 12 March 1853 [N.S.], and though the fighting was confined to the Crimea, it was particularly intense. The capture of Sevastopol and, above all, the death of the Tsar on 9 March 1855 [N.S.] led eventually to the conclusion of the war and a return to the status quo.

- ↑ Historical note: Vietnam still remained closed to foreigners, and its last emperor, Tu Duc, was persecuting the local Christians. A series of demonstrations of naval power and diplomatic missions to Hue in order to secure religious liberty had proved futile, and several French and Spanish missionaries were executed. In 1857, therefore, the governments of these two countries decided to send a joint Franco-Spanish expeditionary force under the command of Admiral Rigault de Genouilly. The admiral had Tourane bombarded and various forts captured before ordering his troops to lay siege to Saigon, which finally surrendered on 17 February 1859. Rigault de Genouilly had originally received no more specific instructions than that he should punish the imperial court at Hue for its persecution of the missionaries. However, as had been the case following the capture of Algeria a few years earlier, the French became entangled in the region, and so after the fall of Saigon this campaign would lead to the gradual and arduous conquest of Indo-China.

- ↑ Historical note: Ever since achieving independence, Mexico had been prey to political and financial instability. The government had run up considerable debts with regard to various European countries. Napoleon III wanted to establish a Catholic Empire there which would be allied to France and would break the hegemony of the United States, but this project was put into action without consulting the most interested party, namely the Mexicans themselves. In 1861, the geopolitical situation appeared to be favourable, since the United States had become enmeshed in civil war. Recovering Mexico's international debts served as the pretext for intervention, and an expeditionary force landed at Veracruz in February 1862. Spain and Britain, however, withdrew their troops after receiving assurances from the Mexican government. The French stayed on, and General de Lorencez decided to march on Puebla. The city held out against the besieging French, and Napoleon III sent reinforcements consisting of 23,000 troops under the command of General Forey. This very costly siege finally ended in May 1863 when Puebla surrendered to the French. Shortly afterwards the invading forces entered Mexico City, where an assembly of notables offered the crown to Archduke Maximilian of Austrian. President Juárez meanwhile retreated to the border with the United States. General Bazaine, the newly appointed commander-in-chief, laid siege to Oaxaca, which surrendered in February 1865. However, a guerilla war developed for which the French forces were not prepared. In April 1865, the American Civil War now over, the United States assisted Juárez's troops and compelled the French to withdraw. Napoleon III ordered the evacuation of his forces, and in February 1867 the last French ship set sail from Mexico. Abandoned by the French, Maximilian was taken prisoner and executed by firing squad at Querétaro in June 1867.

- ↑ André Castelot mentions this in his book on the Mexican expedition: Maximilien et Charlotte du Mexique (2002). According to him, General Weygand, who was born in Mexico, may have been the son of Détroyat, though he then goes on to reject that hypothesis as he does many others!

- ↑ This transatlantic mail boat, which was put into service in 1865, still had sails, but, crucially, it was equipped with an auxiliary steam engine capable of powering two paddles. It could cross the Atlantic in less than thirty days.

- ↑ This phrase is attributed to Barbey d'Aurevily by other sources.

- ↑ Historical note: Having fallen for the bait which Bismarck held out to him, Napoleon III declared war on Prussia on 19 July 1870. After the general mobilisation the French armies suffered a series of defeats. Following the decisive one at Sedan on 1 September Napoleon III was taken prisoner. On 4 September, the re-establishment of the Republic was proclaimed in Paris and a Government of the National Defence was formed. On 19 September, Paris was encircled by the Prussians and Gambetta left the city in a hot air balloon that took him to Tours. The other members of the government withdrew to Bordeaux. An armistice was signed on 28 January 1871, eventually leading to the Treaty of Frankfurt on 10 May whereby France surrendered Alsace and Lorraine to the German Empire that had been proclaimed at Versailles four months earlier. In February, elections to the National Assembly were held. The people of Paris rioted on 18 March, and this insurrectionary movement led to the establishment of the Commune. The latter was suppressed during the so-called 'bloody week' of 21–28 May by troops sent by the government at Versailles. The last German occupation forces did not leave French soil until 1873, when the war indemnity of 5 billion francs had been paid off fully.

- ↑ For further information on Détroyat's acquaintance and tentative collaboration with Tchaikovsky, see the work history for La Courtisane and the presentation of the composer's letters to Détroyat in Tchaikovsky Research Bulletin No. 2 — translator's note.

- ↑ These financial problems induced Hélène Détroyat to welcome the marriage of her son Maurice with Ermelinda, the daughter of a wealthy Brazilian family he had become acquainted with at Fontainebleau a few weeks after the death of his father.

- ↑ Ramon Del Valle was the offspring of one of the wealthy Jewish families that had lived in Saint-Esprit, opposite Bayonne, before the French Revolution.

- ↑ 10ème division 3/68.

- ↑ The son in question is Maurice Détroyat (1868–1951), alumnus of the École Polytechnique, and maternal grandfather of the author of this essay.

- ↑ A biography of the famous French test pilot Michel Détroyat by Paul Magneron is entitled Michel Détroyat. Écuyer du ciel (1957), and it is the subtitle of this which is being cited above — translator's note.