Letter 2259

| Date | 10/22 April 1883 |

|---|---|

| Addressed to | Wladyslaw Pachulski |

| Where written | Paris |

| Language | Russian |

| Autograph Location | Washington (District of Columbia, USA): The Library of Congress, Music Division |

| Publication | Советская музыка (1959), No. 12, p. 66–69 П. И. Чайковский. Полное собрание сочинений, том XII (1970), p. 111–116 |

Text and Translation

| Russian text (original) |

English translation By Brett Langston |

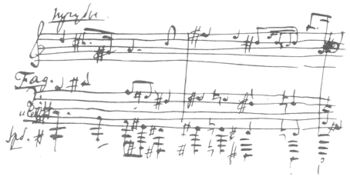

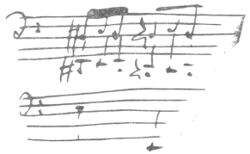

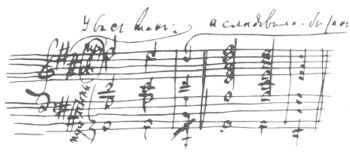

Париж 10/22 апр[еля] 1883 Владислав Альбертович! Прежде всего поговорю с Вами о Ваших контрапунктических работах. Что такое контрапункт? Слово это звучит громко, страшна, и незнающие воображают, что это какая-то музыкальная тарабарщина. Между тем ничего нет проще. Контрапункт есть консонансовая комбинация двух или нескольких голосов. В простейшей его форме, между верхним голосом или верхними голосами и основным, нет ничего, кроме консонансов, т. е. примы, квинты, терции, сексты, октавы. В более сложных, произшедших от мелодического и ритмического оживления голосов, получаются и диссонансы в двух видах: 1) синкопа, т. е. диссонанс на сильном времени (то, что в современной школе зовётся задержанием), 2) диссонанс на слабом времени, т. е. проходящие ноты, вспомогательн[ые] ноты, камбиаты и т. д. Все эти диссонансы придают контрапунктическим сочетаниям невыразимую красоту и жизненность, но под условием естественного разрешения в консонанс. Долгое время никаких других сочетаний музыкальных звуков не признавали. Позднее приобрёл право гражданства доминантсептаккорд и сделался так самостоятелен, что интервалы, входящие в состав его, по лучили значение как бы консонансов, вследствие чего тритон в обеих формах, малая септима и даже обращение её, секунда, стали употреблять без приготовления, на сильных временах такта, однако ж с соблюдением правил разрешения, т. е. вводный тон в тонику, 4-ую ступень в верхнюю медианту. Когда контрапункт из области вокальной музыки перешёл в инструментальную, то мало-помалу в гармонию проник хроматизм и полная свобода модуляций. Дальше этого контрапункт не пойдёт и не должен идти. Между тем случается в наше время видеть контрапунктические работы, в которых основной принцип контрапункта совершенно упущен из виду. Диссонансы в них встречаются не только в изобилии, не только неприготовленные, не разрешённые, — но в таком почёте и с таким значением, что как-будто на них зиждется все, а естественные консонирующие сочетания суть лишь неизбежное зло, от которого авторы охотно бы уклонились вовсе, если б было возможно. Не скажу, чтобы Ваш контрапункт был примером подобного рода исключительного преобладания консонансов, — но Вы не далеки от этого. На каждом шагу я встречаю в Ваших фугах такие совпадения голосов, которые превышают моё понимание. Это какой-то контрапункт для глаз, а не для слуха. Посмотреть... и голоса имеют вид самостоятельных мелодий, есть жизнь и движение, и видно, что намерения Ваши были хорошие, — но когда начнёшь внутренним слухом прислушиваться, то очень скоро устаёшь, ибо громадное количество диссонансов, модуляций, хроматико-энгармонических последований заставляют беспрестанно останавливаться, чтобы постигнуть тень аккорда, которая свела вместе несколько как бы чуждых друг другу голосов, а иногда даже остановка не помогает. Во многих таких местах я ставил вопросительные знаки, но далеко не одни те только места, где я их ставил, были мне непонятны и странны. Если б везде я отмечал все казавшееся мне неестественным, насильственно подведённым, резким, некрасивым, — то пришлось бы испещрить всю Вашу рукопись до неузнаваемости. Не знаю, чем объяснить это явление. Учитель ли Ваш виноват, недостаточно строго и последовательно ведший Вас по пути контрапунктической премудрости, натура ли Ваша такая, что гибкость, здоровая жизненность, ясность и простота в гармонии и голосоведении трудно даются Вам, — но только фуги Ваши в общем нельзя назвать удачными. Притом же они все ужасно длинны, имеют множество интермедий и вставных эпизодических частей, то слишком бедны модуляциями, т. е. тоника слишком преобладает, то, наоборот заходят так далеко, что потом приходится неестественно скоро возвращаться в тонику и кончать насильственно, неприготовленно. Видно, что Вы хотели писать их хитро, затейливо, — но эти затейливости и хитрости не достигают цели, т. е. не услаждают, а тяготят и утомляют. Как бы я был доволен, если бы между Вашими фугами была бы хоть одна небольшая, с двумя, много тремя проведениями, но светлая, ясная, простая с безупречным голосоведением (ведь я у вас много даже квинт и октав отметил), с уравновешенной формой, ну словом такая, как подобает молодому человеку, стремящемуся очистить свой стиль и научиться из небогатого материала дозволенных и безусловно красивых консонансовых комбинаций сооружать целые, вполне законченные звуковые формы. Конечно, в Ваших фугах встречаются очень милые, пикантные и красивые эпизоды и подробности, и я совсем не хочу сказать, что все сплошь дурно, — но мне бы хотелось, чтобы Вы скорее научились писать мастерски — просто, и, просматривая фуги эти, я испытал разочарование. Фуга с обращением темы (F-dur) была бы, может быть, наиболее безупречна с технической стороны, но и в ней я встретил одиннадцать диссонансов сряду, после того один случайный консонансный аккорд, и затем ещё 4 диссонанса: итого 16 сряду комбинаций, в коих всего один раз слух может отдохнуть на аккорде!!! Перехожу к увертюре. По музыке многое в ней очень мило, напр[имер] первая тема (в мендельсоновском духе) весьма мне по душе. Переход от первой темы к второй слишком тяжеловесен; Вы слишком сразу высказали во всей полноте, первую тему, снабдили её даже заключительным предложением и т. д. и потом, как нечто совершенно новое, начинаете вторую. Конечно, это возможно, ибо в музыке все возможно — но если Вы хотели написать увертюру в классической форме, — то это ошибка. Конец, навеянный Вагнером, мог бы быть гораздо эффектнее, если бы не оркестровка, донельзя густая и вместе с тем недостаточно выделяющая главной мысли. Вообще оркестр Вам ещё чужд. Очень бы советовал Вам упражняться и писании для малого оркестра (без тромбонов) и по возможности умеренно употребляя трубы, а партитуре я сделал несколько замечаний, на которые попрошу Вас обратить внимание. Местами Вы пишете так, что невозможно играть, даже иным инструментам Вы дали ноты, коих они вовсе но имеют. Но главный недостаток оркестровки — это чрезмерное обилие подробностей, смущающих самое напряженное внимание и лишающих оркестр Ваш силы и ясности. Какое бы Вы испытали разочарование, если б услышали в исполнении многие места, красивые для глаз, — но не удовлетворяющие тре-бованиям слуха? Это, впрочем, судьба всех начинающих композиторов. Только очень редкие из них бывали одарены таким чутьём оркестра, что, почти не учившись, уже проявляли мастерство. В марше оркестровка гораздо лучше, хотя и тут Вы с медью не церемонитесь. Напр[имер], как это будет звучать грубо, когда две трубы играют тему и как странно Вы располагаете басы местами? Напр[имер], тут: в одном месте такой бас: К чему здесь 1-ый фагот играет solo басовый голос 2-мя октавами выше контрабаса? Ведь его никто не услышит, да и хорошо ли это? А дальше струнные басы делают фигурацию баса, а тромбоны играют его в то же время просто, и при этом до того мешают друг другу, что напр[имер], на сильном времени такта один играют mi, другие re# В тихом темпе марша это очень некрасиво. Трио этого марша хорошо, но ужасно коротко. В конце его очень неоркестровое расположение голосов гармонии. Возможно ли, чтобы в за-ключительной каденции трезвучие на доминанте было пустое, без терции в медной группе? Вот оно: В оркестре, когда играет вся масса, именно середина должна быть полна! Что касается квартета, — то, он из всего присланного Вами нравится мне гораздо больше всего остального; и в отношении изобретения, и по форме он зрелее и солиднее. Я так много Вам наделал замечаний, что, дабы не портить впечатления этой последней похвалы, не сделаю никаких указаний на ошибки в квартете. Да к тому же письменно это так трудно. Бог даст, летом увидимся, и тогда мне и легко и приятно будет побеседовать с Вами о всех этих писаниях. А теперь прошу Вас, добрейший Владислав Альбертович, не смущаться, не огорчаться и не сетовать на меня за множество замечаний, сделанных мною, и вообще за то, что, кажется, больше браню, чем хвалю Вас. Я по опыту знаю, как авторское чувство щекотливо, и чувствую, что довольно резко задеваю чувствительные струны Вашего авторского сердца. Но, дабы похвалы мои имели цену, я должен говорить правду. Да и с какой стати Вы бы нуждались в моих комплиментах? Думаю, что как бы жесток я ни был в своих приговорах, всё-таки эта жестокость полезнее, чем умолчание о недостатках. Однако скажу только: будьте уверены, что я буду очень, очень рад, когда по чистой совести можно мне будет одобрить какое-нибудь будущее Ваше сочинение без всяких оговорок. Если Вы живо чувствуете внутри себя потребность писать, то ни на минуту не теряйте бодрости и терпеливо переносите придирчивость такого критика, как я, тем более строгого, чем искреннее дружеское чувство, которое руководит мной, когда я имею дело с Вашими опытами. Тотчас по отсылке этого письма высылаю Вам все писания Ваши. Простите, что так долго держал их. Ваш П. Чайковский |

Paris 10/22 April 1883 Vladislav Albertovich! First of all I shall discuss your contrapuntal works with you. What is counterpoint? This word sounds loud, frightening, and those who do not know imagine this to be some sort of musical gibberish. Meanwhile, there is nothing simpler. Counterpoint is a combination of two or multiple voices in consonance. In its simplest form, there is nothing besides consonances between the upper voice or the lower voices and the fundamental, i.e. primes, fifths, thirds, sixths, octaves. In more complex situations, produced by melodic and rhythmic animation of the voices, dissonances can arise in two ways: 1) syncopation, i.e. a dissonance on the strong beat (what the modern school calls detention), 2) dissonance on the weak beat, i.e. grace notes, auxiliary notes, cambiata, etc. All of these dissonances endow contrapuntal combinations with inexpressible beauty and vitality, but on the sole condition that they resolve naturally into consonance. For a long time, no other combinations of musical sounds were recognised. Later, the dominant seventh acquired the right of citizenship, and became so independent that the intervals comprising it came to be regarded as consonances, as a result of which both forms of the tritone — the minor seventh and even its inversion, the second — started to be used without preparation, on strong beats of the bar, while still complying with the rules of resolution, i.e. the dominant tone into the tonic, the 4th degree into the upper mediant. When counterpoint moved from the realm of vocal music to instrumental music, little by little, chromaticism and complete freedom of modulation permeated into the harmony. Counterpoint will not go, and should not go, beyond this. Meanwhile, we have occasion in our time to see contrapuntal works which completely lose sight of the basic principle of counterpoint. In these, dissonances are not only found in abundance, not only unprepared and unresolved — but in such pride of place and with such significance that everything seems to depend on them, and natural consonant combinations are merely a necessary evil, which the authors would gladly shun completely, it it were possible. This is not to say that your counterpoint is an example of this type of exceptional predominance of consonances, but you are not so far off it. At every step, I find in your fugues such coincidences of voices that are beyond my understanding. This is a sort of counterpoint for the eyes, but not for the ears. Look... and the voices have the appearance of independent melodies, there is life and movement, and it is clear that you had good intentions — but when you start listening with your inner ear, you very soon become worn out by the huge number of dissonances, modulations and chromatic-enharmonic sequences that compel you to pause continually in order to comprehend the shadow of the chord which brought together several voices alien to one another — and sometimes even pausing does not help. In many such places I inserted a question mark, but it was not only the places where I put them that were strange and incomprehensible to me. If I had noted everywhere everything that seemed unnatural, forced, harsh and ugly to me, then I would have had to cover your entire manuscript beyond recognition. I do not know how to explain this phenomenon. Is it the fault of your teacher for not leading you strictly and consistently along the path of contrapuntal wisdom? Is it that by nature, flexibility, a healthy vitality, clarity in simplicity in harmony and voice control are difficult for you — but only your fugues in general cannot be called successful? Moreover, they are all awfully long, have numerous interludes and inserted episodic parts, are either too poorly modulated, i.e. the tonic is too predominant, or on the contrary, they roam so far that they then have to return to the tonic with unnatural haste, and end forcibly, without preparation. It is clear that you wanted to write them cunningly and intricately — but these intricacies and cunning do not achieve their goal, i.e. they do not delight, but are trying and tiresome. How pleased I would be if in the midst of your fugues there were at least one short one, with two or as many as three layers, but bright, clear and simple, with impeccable voice leading (after all, I even noticed you had many fifths and octaves), with a balanced form — well, in short, as befits a young man striving to purify his style and to learn from the sparse material of legitimate and undoubtedly beautiful consonant combinations, in order to construct whole, and completely realised forms of sound. Of course, your fugues have very nice, piquant and beautiful episodes and details, and I do not want to say at all that everything is thoroughly bad — but I should like you to quickly learn to write like a master — simply, and looking through these fugues, I was disappointed. The fugue with the inversion of the theme (in F major) would, perhaps, be the most impeccable from a technical point of view, but even there I encountered eleven consecutive dissonances, followed by a single random consonant chord, and then a further 4 dissonances: a total of 16 combinations in a row, in which the ear can rest on a chord only once!!! Moving on to the overture. Musically, it has many nice things, for example, the first theme (in the spirit of Mendelssohn) is very much after my own heart. The transition from the first theme to the second is too heavy-handed; you expressed the first in its entirety much too quickly, even bringing it to a complete halt etc., and then you start the second as if it were something entirely new. This is certainly possible, because in music everything is possible — but if you wanted to write an overture in classical form, then this is a mistake. The ending, inspired by Wagner, could have been far more effective were it not for the orchestration, which is impossibly dense, and at the same time does not sufficiently emphasise the main idea. In general, the orchestra is still alien to you. I would strongly advise you to practice writing for a small orchestra (without trombones), and if possible using the trumpets sparingly; I made several comments on the score, which I would ask you to pay attention to. In some places you write in such a way that it is impossible to play; you even gave notes to some instruments that they do not even have. But the principle drawback of the orchestration is the excessive abundance of details, which confuse the most intense listener, and deprive the orchestra of your strength and clarity. How disappointed would you be if you heard many passages performed that are beautiful to the eye, but which do not satisfy the requirements of the ear? However, such is the fate of all aspiring composers. Only the rarest of them have been gifted with such a flair for the orchestra that they already showed their mastery, almost without studying. The orchestration in the march is far better, although even here you do not stand on ceremony with the brass. For example, how rough would this sound when the two trumpets play the theme and how strangely you allocate the bass in places? For example, here: in one place the bass is thus: Why does the 1st bassoon play solo with a bass voice 2 octaves above the double bass? After all, no-one will hear him, and is that a good thing? And the bass strings have a figure in the bass, which the trombones play plainly at the same time, interfering with each other to such an extent that, for example, on a strong beat one is playing E, the other D-sharp. At a slow march pace, this is very jarring. The Trio of this march is good, but awfully short. At the end, there is a most unorchestral arrangement of the voice harmony. Is it possible for the final cadence to omit the triad on the dominant, without having a third in the brass section. This is it: When the orchestra is playing en masse, it is the middle range that should be full. As for the quartet — out of all the things you sent, I like it far more than anything else; both in terms of invention and form, it is more mature and solid. I have made so many remarks to you that, in order not to spoil the impression of the latter praise, I shall not point out any errors whatsoever in the quartet. And besides, I find writing is so difficult. God willing, we shall see each other in the summer, and then it will be easy and pleasant for me to talk with you about everything I have written. But for now I ask you, most kind Vladislav Albertovich, not to be embarrassed, nor upset, and not to grumble at me for the many comments I have made, and generally for the fact that I seem to be scolding you more than praising you. I know from experience how sensitive authorial feelings can be, and I feel that I am quite sharply grating on the sensitive strings of your author's heart. But in order for my praise to have merit, I must tell the truth. But why should you need my compliments? I think that no matter how harsh I may be in my judgements, this harshness is still more useful than keeping silent about the shortcomings. However, I just say this: rest assured that I shall be very, very glad when, in good conscience, I can approve some future work of yours without any reservations. If you feel keenly within yourself the urge to write, then do not lose courage for a moment, and patiently endure the pickiness of a critic like me, who is all the more pedantic through the sincere amicable feeling that guides me when I have dealings with your experiments. Immediately after sending off this letter, I shall dispatch all your writings. Forgive me for keeping them for so long. Yours P. Tchaikovsky |