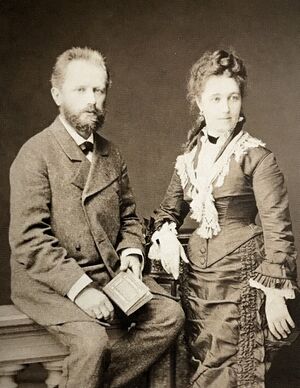

Antonina Tchaikovskaya

Wife of the composer (b. 23 June/5 July 1848; d. 16 February/1 March 1917 at Udelnaya near Saint Petersburg), born Antonina Ivanovna Milyukova (Антонина Ивановна Милюкова); known after her marriage as Antonina Ivanovna Chaykovskaya (Антонина Ивановна Чайковская).

Antonina's role in Tchaikovsky's life is no longer viewed in the one-dimensional terms that used to prevail [1]. It is impossible to deny that she had a very negative effect on the composer's psychological and physical state, a fact that is confirmed by Tchaikovsky's own statements in his letters and diaries. Tchaikovsky called his wife a "terrible wound" — he felt heavily burdened by his legal bind and sometimes even afraid of possible "disclosures" by her concerning his homosexual preferences. Antonina's own recollections, which present her side of the story, have been labelled the product of a rash and insane woman, and therefore ignored. Recent archival studies have made it possible to clarify several key details relating to Antonina's origins, and the history of the couple's acquaintance, marriage, further relationship and her life after their separation.

Early Life

Antonina Milyukova was born into a family of the hereditary gentry that resided outside Moscow in the Klin region. The family traced its ancestry to the 14th century. Antonina's parents, Ivan Milyukov and his wife Olga, separated in 1851, and her childhood was spent in an unfavourable emotional environment. She was brought up in a private Moscow boarding school under the supervision of her mother (1851–55), and then at her father's Klin estate (1855–58). Together with her older brothers Aleksandr and Mikhail, and her elder sister Yelizaveta (Adel), she received a standard home education, including the study of two foreign languages.

From an early age Antonina enjoyed music (her father Ivan Milyukov kept a peasant orchestra). She continued her education at the Moscow Institute of Saint Elizabeth, completing the full course of study from 1858 to 1864. Here, apart from the required subjects, she took piano and voice lessons. In the 1873/74 academic year she studied at the Moscow Conservatory, where her piano teacher was Eduard Langer, and her teacher in elementary theory was Karl Albrecht. After leaving school, Antonina pursued a career in pedagogy, giving private lessons in Moscow in the 1870s, and then teaching at a school attached to the Kronstadt House of Industry in 1896. On several occasions, Antonina unsuccessfully attempted to become a teacher in various other educational institutions.

First Encounters

Antonina met Tchaikovsky for the first time in Moscow in late May 1872, at the apartment of her brother, the staff-captain Aleksandr Milyukov (1840–1885), whose wife Anastasia (née Khvostova) had been a close friend of the composer from his days at the School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg.

Antonina later admitted, both in her letters to Tchaikovsky (1880s) and in her recollections (1893), that this first meeting made an indelible impression on her, resulting in a profound affection that lasted for many years. She lent special meaning to the fact that her love arose from her attraction to Tchaikovsky's appearance and purely human qualities, and that she was utterly ignorant of his music and growing fame in cultural circles. At Tchaikovsky's personal invitation, Antonina attended the premiere of his Cantata for the Opening of the Polytechnic Exhibition in Moscow on 30 May/11 June 1872. Their relationship, however, did not develop in the years after their first meeting, and it was only during Antonina's studies at the conservatory that they briefly saw each other within the walls of this institution. As Antonina later wrote, she loved Tchaikovsky "secretly" for over four years. In late 1876, Antonina received a small inheritance due to the division of the family estate. This potential "dowry" was apparently the immediate incentive for taking active steps towards renewing her acquaintance with the composer.

On 26 March/7 April 1877, Antonina sent Tchaikovsky a written confession of her love for him. Both she and Tchaikovsky testified that they "began a correspondence", as a result of which the composer received her offer "of hand and heart" already in the early days of May 1877.

On 20 May/1 June, she met Tchaikovsky. An analysis of her surviving letters suggests that in all likelihood their personal meeting was initiated by the composer himself. The threat of suicide, made in the last letter she wrote before their meeting, cannot be considered a serious factor in Tchaikovsky's eventual decision; in the context of the entire letter, this "threat" seems to be no more than a device in the tradition of sentimental models from so-called "letter books", which were popular at the time and which contained samples of fictional letters for all occasions.

The meeting occurred in the house where Antonina was renting a room, on the corner of Tverskaya Street and Maly Gnezdnikovsky Lane in Moscow. At the next meeting, on 23 May/4 June, Tchaikovsky made a formal proposal, promising his bride only his "brotherly" love, to which she readily agreed. But Tchaikovsky chose not to mention this meeting in his letter to Modest, written on the same day. Instead he sought to explain his cooling off with regard to Kotek, and even began to see the manifestations of Providence in various coincidences that had recently happened:

You will ask about my love? It has once again fallen off almost to the point of absolute calm. And do you know why? You alone can understand this. Because two or three times I saw his injured finger in all of its ugliness! But without that I would be in love to the point of madness, which returns anew each time I am able to forget somewhat about his crippled finger. I don't know whether this finger is for the better or worse? Sometimes it seems to me that Providence, so blind and unjust in the choice of its protégé's, deigns to take care of me. Indeed, sometimes I begin to consider some coincidences to be not mere accidents... Who knows, maybe this is the beginning of a religiosity that, if it ever takes hold of me, will do so completely, i.e., with Lenten oil, cotton-wool from the Iveron icon of the Mother of God, etc. I am sending you a photograph of myself and Kotek together. It was taken at the very peak of my recent passion.

Marriage

The marriage took place at Saint George's Church in Moscow on 6/18 July 1877. The bridegroom's witnesses were his brother Anatoly and his friend Iosif Kotek, the bride's were her close friends Vladimir Vinogradov and Vladimir Malama. They were joined by the priest Dmitry Razumovsky, who was also professor of history of church music at the conservatory.

The majority of biographical works on Tchaikovsky date the beginning of his relationship with Antonina to early May 1877, the time of the genesis and first drafts of his opera Yevgeny Onegin. According to the composer's own testimony in his letters to Nadezhda von Meck, an important factor in their rapid intimacy and marriage was Tchaikovsky's fascination with the plot of Pushkin's novel — his sympathy for the heroine and his desire to avoid "repeating" Onegin's cruelty towards a woman who loves him. Another significant factor was Antonina's own insistent requests for meetings, accompanied by threats to commit suicide in case of a refusal. The fact that there remained about two weeks before the idea of the opera Yevgeny Onegin took root in Tchaikovsky's mind, after being suggested by the singer Yelizaveta Lavrovskaya on 13/25 May, allows one to conclude that the choice of Pushkin's novel as the plot for an opera could have been stimulated by Tchaikovsky's personal situation: a distant female acquaintance confessing her love in a letter.

From the very beginning of his married life, Tchaikovsky greatly suffered from his new predicament. He quickly realised that he had made a grave mistake. Moreover, he found himself unable to accept the personality and character of his wife as well as her family and circle of friends. After 20 days of cohabitation their marriage was still not consummated. It is uncertain whether Tchaikovsky had confided in his wife at the outset regarding the problem of his homosexuality or whether she may simply have disregarded such a confession. On 27 July/8 August, Tchaikovsky left her for one-and-a-half months, travelling to Kamenka to stay with his sister.

After returning to Moscow, the composer lived with his wife from 12/24 September to 24 September/6 October at their apartment on Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street (not far from the conservatory), before leaving her for good. In the first instance, Tchaikovsky contrived to be summoned to Saint Petersburg on a fictitious errand, and thereupon he departed abroad for a considerable period of time in order to recuperate from a nervous breakdown which, as it transpires from archival documents, was faked.

Be that as it may, there hardly remains any doubt that his homosexuality, coupled with the psychological incompatibility on which he insisted in his correspondence, proved the ultimate cause of the break-up of his marriage. This recognition forced Tchaikovsky to admit that he had failed in his plan to enhance his social and personal stability. Most importantly, however, his impulsive marriage helped him to realise that his homosexuality could not be changed and had to be accepted as it was. That Tchaikovsky at some point came to think of it as "natural" follows from his use of that very term in a letter to his brother Anatoly on 13/25 February 1878 from Florence: "Only now, especially after the tale of my marriage, have I finally begun to understand that there is nothing more fruitless than not wanting to be that which I am by nature".

There is not a single document from the rest of his life that can be construed as an expression of self-torment on account of his homosexuality. Some occasional expressions of nostalgia for family life are perfectly understandable in a bachelor, and have nothing to do with sexual orientation. Tchaikovsky's eventual solution in his private life became, while often entertaining passionate and even sublime feelings for young males among his social peers, including his pupils, to gratify his physical needs by means of anonymous encounters with members of the lower classes. In between was his manservant Aleksey Sofronov ("Alyosha"), whose status changed over the years from one of bed-mate to that of a valued friend, who eventually married with Tchaikovsky's blessing, but stayed in his household till the very end. At the end of his life, the composer succeeded in creating an emotionally satisfying environment through close family relationships, and by surrounding himself with a group of admiring young men, headed by his beloved nephew Vladimir Davydov.

Separation

Tchaikovsky undertook several attempts at divorce between 1878 and 1880, but without success, since for a long time Antonina continued to believe in the possibility of some sort of future "reconciliation", and refused to agree to what her husband proposed, thereby invoking his wrath, with accusations of stupidity, suspicions of "blackmail", etc. Only in 1881 did Tchaikovsky finally abandon the idea of divorce. At this time he ceased paying his wife the pension he had promised her (it had fluctuated from 50 to 100 rubles a month), on the grounds of her erratic and unpredictable behaviour.

Between 1881 and 1884 Antonina had three illegitimate children by Aleksandr Aleksandrovich Shlykov (d. 1888), a lawyer with whom Antonina lived from May 1880 after she resigned herself to the fact that Tchaikovsky did not want to see her again. Due to her financial vulnerability and "semi-legal" social situation, as well as the constant illnesses of both herself and her common-law husband, Antonina surrendered all three of these children in a foundling hospital in Moscow, from which they seem to have been sent to live with peasant families in the environs of the city (as was the practice with such state orphanages until the children reached a certain age, when they would be taken back to the city in order to receive an education that would allow them to fend for themselves in life). Sadly, all three of Antonina's children died during early childhood:

- Mariya Aleksandrovna (b. 13/25 February 1881; d. 2/14 January 1882)

- Pyotr Petrovich (b. 24 August/5 September 1882; d. 9/21 June 1890)

- Antonina Petrovna (b. 24 October/5 November 1884; d. 8/20 March 1887)

Although this decision to give away her children to an orphanage might at first glance seem very cruel on her part, Antonina was acting on the following considerations: firstly, Shlykov was incapable of maintaining a young family since he suffered from chronic ill-health (which meant that Antonina had to devote most of her energies to nursing him, even though he seems to have treated her roughly); and, secondly, if she had tried to keep her children at home this would have meant that she would have had to register them as legitimate, that is under the surname of Tchaikovsky, since her marriage to the composer was never annulled. At the foundling hospital no surnames were asked for, and in this way Antonina wanted to save Tchaikovsky from this potential disgrace and burden on his finances. For even after the great injury that the separation forced on her in the autumn of 1877 entailed for her feelings and dignity, she did not cease to love the composer, and in one of the several letters which she sent him over the following years (mostly via Pyotr Jurgenson's office in Moscow) she entreated Tchaikovsky to adopt one of her children, providing details of how he might locate the child through the orphanage.

Yet Tchaikovsky was also deeply concerned over the entire fiasco, and felt sincere remorse for his apparently cruel treatment of Antonina. Paradoxically, it is precisely the years from 1877 to 1880 — the most difficult time in Tchaikovsky's marital drama — that stand out as one of his most productive periods in a creative sense. Subsequently Tchaikovsky was plagued with pangs of conscience: for instance, in his letters to Pyotr Jurgenson from 1883 and 1888, where he asks his publisher to locate his abandoned spouse in order to help her materially. Tchaikovsky appreciated his wife's musical abilities, which is evident by a series of favourable judgements found in his letters. But Tchaikovsky often perceived Antonina's personal qualities unfairly, painting a distorted picture of her, based on his irritation at this or that trait of her character (for instance, in his letters to Nadezhda von Meck, his brothers, and others). One of Tchaikovsky's more balanced statements in respect to his wife can be found in a letter to his sister Aleksandra, written from Rome on 8/20 November 1877: "I give full justice to her sincere desire to be a good wife and friend to me, and... it is not her fault that I did not find what I was looking for." The fact remains that, despite her ruined family life and perennial pain, not once did Antonina attempt to "avenge" her husband. On the contrary, she even embellished slightly the composer's human image in her recollections: "No one, not a single person in the world, can accuse him of any base action".

In 1886, after a five-year silence, Antonina Milyukova presented the composer a request for material assistance, as well as a suggestion that he adopt and take in her youngest daughter, Antonina. Tchaikovsky readily agreed to support his wife financially and appointed her once again a monthly pension of 50 rubles (later increased to 100, then to 150, then lowered again to 100 rubles). He failed to respond to the idea of adopting her child, although it is known from Tchaikovsky's letters to his brother Modest and Pyotr Jurgenson that he sharply condemned the very fact that Antonina's children were at a foundling hospital.

Between 1886 and 1889, Antonina regularly wrote Tchaikovsky to thank him for his material support, even sending him a shirt she had sewn as a token of gratitude; she told him of her life and misfortunes (her civil husband died in 1888), asked him to increase the pension, and offered to join him again. Tchaikovsky reacted painfully not only to Antonina's letters themselves, but also to information concerning her attempts to seek patronage from the Empress and Anton Rubinstein, in order to find a permanent teaching position. The composer considered the amount he was paying his wife to be fully adequate for a comfortable existence and viewed Antonina's "social legitimization" as a threat to his prestige.

Throughout these years, Pyotr Jurgenson served as the mediator between husband and wife so that they could avoid personal contact. They met from time to time at concerts and operatic performances, seeing each other only from a distance. Antonina maintained that their last meeting took place in Moscow in the autumn of 1892 during a stroll in the Aleksandrovsky Gardens. She recalled that Tchaikovsky walked behind her but "could not make himself speak" to her. This meeting was probably fictitious.

Last Years

After the composer's death, she received a pension of 100 rubles a month, which Tchaikovsky left her in his will. She moved from Moscow, where she had resided all her earlier life, to live in Saint Petersburg and settled near to the Saint Aleksandr Nevsky Monastery where Tchaikovsky was buried. Antonina's further fate was tragic: soon after the composer's death she began to display signs of an emotional disorder (a mania of persecution). By 1896 the condition had worsened and she moved to Kronstadt, where she sought spiritual support and a cure from the renowned miracle-worker Father John of Kronstadt. For some unknown reason the priest refused to help her. In October 1896, Antonina ended up in the Saint Petersburg Hospital of Saint Nicholas the Wonderworker for the emotionally disturbed. After her relative recovery, in February 1900, she was released from the hospital, only to return there in June of 1901 with a diagnosis of paranoia chronica. A month later, with the help of Tchaikovsky's brother Anatoly, she was transferred to a more comfortable psychiatric hospital outside the city — the Charitable Home for the Emotionally Disturbed at Udelnaya. The pension of her late husband served as payment for her room and board. She spent the last ten years of her life at this institution more as a "resident" than a patient. The home provided her with medical supervision in her old age, with attentive care by the personnel, and full living conveniences. She died of pneumonia on 16 February/1 March 1917, and was buried at the Uspensky Cemetery in Saint Petersburg. Her grave has not survived.

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

4 letters from Tchaikovsky to his wife Antonina have survived, dating from 1878 to 1890, all of which have been translated into English on this website:

- Letter 720a – 8/20 January 1878, from San Remo

- Letter 822a – 1/13 May 1878, from Kamenka

- Letter 1168a –30 April/12 May 1879, from Kamenka

- Letter 4019 – 30 January/11 February 1890, from Florence

16 letters from Antonina Tchaikovskaya to the composer, dating from 1877 to 1890, are preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin (a4, Nos. 4613–4628).

Bibliography

- Московский фельетон. Болезнь Чайковского (1877)

- У вдовы П. И. Чайковского (1893)

- Из воспоминаний вдовы П. И. Чайковского (1894)

- Женитьба П. И. Чайковского (1902)

- Tchaikowsky's peculiar marriage (1910)

- Tchaikowsky's peculiar marriage (1912)

- Воспоминания вдовы П. И. Чайковского (1913)

- Из воспоминаний о П. И. Чайковском (1918)

- Tchaikowski's strange marriage (1924)

- Eugene Onegin and Tchaikovsky's marriage (1934)

- Eugene Onegin and Tchaikovsky's marriage (1939)

- Eugene Onegin and Tchaikovsky's marriage (1970)

- Eugene Onegin and Tchaikovsky's marriage (1980)

- Tchaikovsky's marriage (1982)

- Три диалога о любви. Из переписки П. И. Чайковского и воспоминаний современников (1990)

- Von Meine Erinnerungen an Peter Tschaikowski (1992)

- Nikolay Kashkin (1993)

- Антонина Чайковская. История забытой жизни (1994)

- Интервью А. И. Чайковской Петербургской газете (1994)

- Sich selbst nannte er eine Mischung aus Kind und Greis (1994)

- Воспоминания А. И. Чайковского (1994)

- Письма А. И. Чайковской (Милюковой) к П. И. Чайковскому (1994)

- Письма А. И. Чайковской к разным лицам (1994)

- Странная женщина (1994)

- Женщины, так и не ставшие судьбой Чайковского (1995)

- Письмо в редакцию (1995)

- Семейная драма Петра Ильича (1995)

- A most unusual triangle (1996)

- Жена композитор (1996)

- Antonina Čajkovskaja. Geschichte eines vergessenen Lebens. Uber das Buch von Valerij S. Sokolov (Moskau 1994) (1997)

- Tchaikovsky (1998)

- Nikolay Kashkin (1999)

- Antonina Tchaikovskaya (1999)

- Tchaikovsky (2000)

- Weibliche Zuwendung und Geborgenheit (2004)

- Existenzkrise und Tragikomödie. Čajkovskijs Ehe. Eine Dokumentation (2006)

- Пётр Чайковский. Бумажная любовь (2009)

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ The main part of this article is based on Alexander Poznansky's preamble to Antonina's recollections of her husband in Tchaikovsky through others' eyes (1999), p. 102-111.