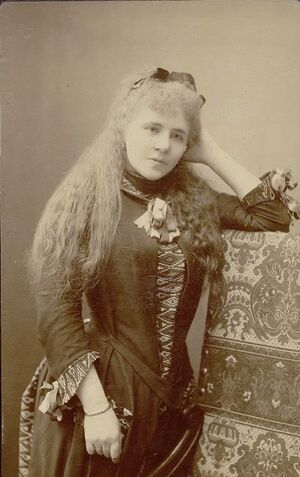

Emiliya Pavlovskaya

Opera artist (soprano) and friend of the composer (b. 28 July/9 August 1853 in Saint Petersburg; d. 23 March 1935 in Moscow), born Emiliya Karlovna Bergmann [1] (Эмилия Карловна Берман); known in her stage career as Emiliya Karlovna Pavlovskaya (Эмилия Карловна Павловская).

After graduating from the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in 1873, where she was a student in Professor Camillo Everardi's singing class, Emiliya toured Italy and other western European countries. Between 1876 and 1883 she sang in the operatic theatres in Kiev, Odessa, Tiflis and Kharkov. In the 1883–84 and 1888–89 seasons she was an artist at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, and spent the intervening years at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. In later life she became a teacher. She continued to work as a coach for young singers at the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre after the October Revolution in 1917, and the Soviet government later bestowed on her the titles "Hero of Socialist Labour" and "Merited Artist of the Russian SFSR".

Tchaikovsky and Pavlovskaya

Tchaikovsky was impressed when he heard Pavlovskaya for the first time in La Traviata at the Kiev Opera on 8/20 September 1877 [2]. After being introduced to her towards the end of 1883, when she was singing Tatyana in Yevgeny Onegin at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, Tchaikovsky came to regard her as an exceptionally talented, clever, and gifted opera artiste. In his opinion she was the best exponent of the roles of Tatyana and Mariya in Mazepa. Emiliya Pavlovskaya premiered the role of Mariya in the latter opera in 1884, as well as that of Nastasya / Kuma in The Enchantress (1887).

The composer frequently visited Pavlovskaya's house, where he invariably found a warm and cordial atmosphere. In her memoirs of Tchaikovsky she recounted a conversation which they had in Moscow, evidently in May 1885, when the situation at the Conservatory had become critical due to Karl Albrecht's unpopularity as director of the institution:

Pyotr Ilyich once came to me, frightfully worked up, and told me that he had just been to see Anton Rubinstein and had come straight to me to ask my advice. He had been invited to become director of the Moscow Conservatory and Rubinstein was trying to persuade him to accept this offer; Pyotr Ilyich was terribly worried and didn't know what to do.

I resolutely set about dissuading him from accepting the offer, as I knew very well his forgetfulness, his soft character, his nervousness, and the complete absence of any administrative streak in him. I said to him:

Why, Pyotr Ilyich what kind of administrator would someone like you or I make?! I mean, the very next morning you would find that you had no power to control events yourself, that it isn't you who's the administrator, but rather everyone else will be manipulating you! No, one really shouldn't take on a task for which one feels neither the vocation nor has the right aptitudes.

He immediately sat down to write out a telegram for Rubinstein in which he turned down this honour" [3]}.

Instead, Tchaikovsky used his influence with the Russian Musical Society to successfully lobby for the appointment of Sergey Taneyev to the directorship of the Moscow Conservatory, since he had absolute confidence in the integrity and abilities of his former student.

Pavlovskaya also recalled a trait in Tchaikovsky's character, which may explain why he was able to evoke so vividly the scrambling of the mice in the battle scene of The Nutcracker:

This may sound funny, but I cannot resist noting one trifling detail. We both shared a fear of mice. Just like me, he too was terribly afraid of them. The sight of these little rodents was enough to fill us with terror" [4].

Tchaikovsky also met Pavlovskaya frequently at the house of Vladimir Pogozhev in Saint Petersburg, where she would perform his songs and arias from his operas for the assembled guests. Their friendship, however, cooled somewhat after the failure of Tchaikovsky's opera The Enchantress, which was largely due to Pavlovskaya's unsatisfactory performance as the heroine Nastasya. At the rehearsals for this opera in October 1887, Tchaikovsky noticed that she had lost her voice, but since two years earlier he had promised her that she would sing the title-role in The Enchantress, he felt he could not offend her by letting another singer take over the part of Nastasya at the premiere on 20 October/1 November 1887. In a letter to Tchaikovsky ten days later (after subsequent performances of the opera had played to ever dwindling audiences), Pavlovskaya admitted that she was probably to blame for this fiasco, and wrote: "You know how I love you, your Enchantress, and all your music. Your success means a lot to me — it is the success of talent, wonderful music, and truth — and my wish and advice to you, as a friend who loves you sincerely, is that for Moscow you should pick another Nastasya, even if next year I am engaged there". The ending of this same letter also shows that she was aware that Tchaikovsky was inwardly angry with her: "When you left, on 7/19 November 1887, that is at the moment of our parting, my heart was simply torn to pieces… but I could not say it otherwise!… Something has happened between us (on your part), some dark cloud has come over me… I don't understand… but I can feel it, and it hurts me very, very much" [5]. The following year Tchaikovsky wrote just three letters to Pavlovskaya, and after that their once so lively correspondence came to an end.

Dedications

In 1884, Tchaikovsky dedicated his song Do Not Ask — No. 3 of the Six Romances, Op. 57 — to Emiliya Pavlovskaya.

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

40 letters from Tchaikovsky to Emiliya Pavlovskaya have survived, dating from 1884 to 1888, all of which have been translated into English on this website:

- Letter 2424 – 4/16 February 1884, from Moscow

- Letter 2613 – 1/13 December 1884, from Paris

- Letter 2630 – 29 December 1884/10 January 1885, from Moscow

- Letter 2649 – 26 January/7 February 1885, from Moscow

- Letter 2661 – 20 February/4 March 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2672 – 14/26 March 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2677 – 1/13 April 1885, from Saint Petersburg

- Letter 2685 – 12/24 April 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2698 – 28 April/10 May 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2705 – 7/19 May 1885, from Saint Petersburg

- Letter 2708 – 9/21 May 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2710 – 18/30 May 1885, from Moscow

- Letter 2741 – 20 July/1 August 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2747 – 10/22 August 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2762a – 9/21 September 1885, from Maydanovo

- Letter 2932 – 17/29 April 1886, from Tiflis

- Letter 3013 – 25 July/6 August 1886, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3096 – 13/25 November 1886, from Klin

- Letter 3141 – 2/14 January 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3144 – 13/25 January 1887, from Moscow

- Letter 3149 – 20 January/1 February 1887, from Moscow

- Letter 3150 – 20 January/1 February 1887, from Moscow

- Letter 3152 – 21 January/2 February 1887, from Moscow

- Letter 3164 – 27 January/8 February 1887, from Moscow

- Letter 3192 – 2/14 March 1887, from Saint Petersburg

- Letter 3236 – 23 April/5 May 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3297 – 23 July/4 August 1887, from Aachen

- Letter 3306 – 30 July/11 August 1887, from Aachen

- Letter 3337 – 3/15 September 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3338 – 3/15 September 1887, from Klin

- Letter 3346 – 10/22 September 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3347 – 11/23 September 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3358 – 19 September/1 October 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3361 – 21 September/3 October 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3363 – 22 September/4 October 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3370 – 26 September/8 October 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3415 – 24 November/6 December 1887, from Maydanovo

- Letter 3536 – 28 March/9 April 1888, from Tiflis

- Letter 3707 – 22 October/3 November 1888, from Moscow

- Letter 3708 – 25 October/6 November 1888, from Moscow.

32 letters from Emiliya Pavlovskaya to the composer, dating from 1885 to 1887, are preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin (a4, Nos. 3188–3218 and 6634).

Bibliography

- П. И. Чайковский и Э. К. Павловская (1934)

- Переписка Чайковского. П. И. Чайковский и Е. К. Павловская (1940)

- Из моих встреч с П. И. Чайковским (1962)

- Из моих встреч с П. И. Чайковским (1973)

- Из моих встреч с П. И. Чайковским (1979)

- Из моих встреч с П. И. Чайковским (1980)

- Emiliya Pavlovskaya (1993)

- Рождение русской Кармен (2012)

External Links

- Wikipedia (Russian)

Notes and References

- ↑ Or "Berman", according to some sources.

- ↑ See Letter 599 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 9/21 September 1877.

- ↑ Из моих встреч с П. И. Чайковским (1980), p. 149–150.

- ↑ Из моих встреч с П. И. Чайковским (1980), p. 148–150 (150). See also Letter 1967 to Nadezhda von Meck from Naples, 13/25–14/26 February 1882: "I suffer a shameful weakness: I am afraid to the point of insanity (literally) of mice. Imagine, dear friend, that at this moment, as I write to you, above my head in the attic, perhaps a whole army of mice should be conducting manoeuvres. If even one of them falls into my room, I am condemned to an agonizing, sleepless night!". Quoted here from Tchaikovsky (2009), p. 417.

- ↑ Letter from Emiliya Pavlovskaya to Tchaikovsky, 30 November/12 December 1887. This and many other letters from Pavlovskaya to the composer (as well as all of Tchaikovsky's extant letters to her) have been published in Переписка Чайковского. П. И. Чайковский и Е. К. Павловская (1940).