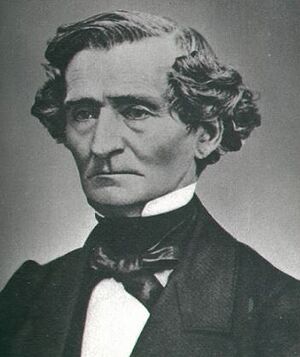

Hector Berlioz

French composer (b. 11 December 1803 [N.S.] at La-Côte-Saint-André, near Lyons; d. 8 March 1869 [N.S.] in Paris), born Louis-Hector Berlioz.

Tchaikovsky and Berlioz

In his Autobiography of 1889, Tchaikovsky noted how his revered teacher Anton Rubinstein had encouraged him in every way at the Conservatory, but had always been sceptical about his enthusiasm for the new tendencies in music, and, in particular, his desire "to follow in the footsteps of Wagner and Berlioz". This reference to the French Romantic composer reflects the fascination which the author of the Symphonie fantastique, with his bold harmonic and orchestral effects, exerted on the younger generation of Russian musicians. For it was not just Tchaikovsky, but also the members of the "Mighty Handful", who admired Berlioz for his orchestration and the imaginative power of his programme music. Already during his first visit to Russia in 1847, Berlioz had been praised to the skies by Vladimir Stasov and the Romantic writer and critic Vladimir Odoyevsky (1804-1869) as the herald of a new school of music. In December 1867, when Berlioz made his second tour of Russia (he had been invited by Mily Balakirev to conduct several concerts in Saint Petersburg and Moscow), Tchaikovsky had the chance to meet the veteran composer, who was delighted to find so many enthusiastic admirers of his music in Russia at a time when he was not so popular in France. As Nikolay Kashkin recalled, at a banquet given in Berlioz's honour at the Moscow Conservatory Tchaikovsky delivered "a wonderful speech in French" outlining the illustrious guest's achievements. Modest Tchaikovsky, describing this episode in his biography of the composer, summed up his brother's attitude to Berlioz:

Whilst he bowed down before the significance of Berlioz in contemporary music and gave him his due as a great reformer, chiefly in the sphere of orchestration, Pyotr Ilyich did not feel any enthusiasm for his music. I think that already then the opinion which he later expressed in his articles had already taken shape. But, although he displayed a sober attitude, free of any blind enthralment, towards Berlioz's works, he felt otherwise about Berlioz's personality during his visit to Moscow. In the eyes of the young composer the latter was above all, as he himself says [in TH 277], the embodiment of 'selfless hard work and ardent love of art', and a warrior in 'the noble and resolute struggle against the obscurantism, obtuseness, routine, intrigues, and ignorance of that menacing collective entity which the poets refer to as the multitude. Moreover, he was an old man worn down by the years and by illness, persecuted by Fate and by people, and for Pyotr Ilyich it was gratifying to be able to comfort him and warm his heart even just for a moment with a fiery manifestation of sympathy. Finally, in the person of Berlioz there stood before him the first great composer whose acquaintance he had had occasion to make, and the feeling of piety which as a young artist he understandably felt for his great colleague could not leave him indifferent. Like everyone who seriously loved music in Russia, he received Berlioz enthusiastically and all his life retained fond memories of his meeting with him [1].

It is worth noting, though, that despite his reservations about Berlioz's music in general, Tchaikovsky expressed great enthusiasm for La damnation de Faust (see below).

Tchaikovsky had studied Berlioz's famous Traité d'instrumentation et d'orchestration (first published in Paris in 1843–44 and subsequently republished many times, including in other languages — Tchaikovsky owned a copy of the 1864 German edition, published in Leipzig [2]. He also read with great interest the French master's Memoirs (published posthumously as a single volume in 1870), and he frequently quoted whole excerpts from them in his music review articles (e.g. in TH 282 and TH 285). Vasily Yastrebtsev (1866–1934), a future biographer of Rimsky-Korsakov, recalled a meeting with Tchaikovsky in Saint Petersburg in October 1887 during which the latter had spoken at length about Berlioz and his "incomparable instrumentation". Despite his reservations about Berlioz's music (see below), he had even pointed to a certain affinity, since, like Berlioz, his writing for the orchestra often involved "extremely complex textures" [3]. Another point of contact between the two composers is that the idea for writing a symphony based on Byron's Manfred, which Balakirev proposed to Tchaikovsky in 1882 (although it was not until three years later that Tchaikovsky actually set about his Manfred symphony), had originally been suggested to Balakirev by none other than Berlioz back in 1868!

Tchaikovsky admired Berlioz for his artistic integrity and the way that he had always persevered in his pursuit of the ideal despite the many frustrations he had endured in life. Similarly, Herman Laroche observed how his late friend would often quote Berlioz's famous words: "Pensez-vous que c'est pour mon plaisir que je fais de la musique?" to refute those who were inclined to see in music no more than pleasant entertainment [4].

General Reflections on Berlioz

In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles

- TH 277 — provides a detailed appraisal of Berlioz, noting how "fiery poetic imagination" predominated in his works over "pure musical creativity", and that, although Berlioz sometimes achieved "miracles of orchestration" and even a certain "beauty of sound", he was unquestionably inferior to Mozart and Beethoven.

- TH 282 — quotes extensively Berlioz's description of the premiere of Weber's Der Freischütz in Paris in 1824, and calls this "the tribute of a great artist to another great artist".

- TH 285 — after quoting Berlioz's account of the genesis of Harold en Italie, Tchaikovsky makes some observations on how his music was always infused with a "deeply felt poetic spirit", but often marred by the "clumsy and awkward execution" of his ideas.

- TH 299 — gives a remarkable comparison between Berlioz and Beethoven, noting how for the latter "orchestral colour" was always a means to an end, whereas for Berlioz it was very often the reverse.

In Tchaikovsky's Letters

- Letter 1005 to Nadezhda von Meck, 5/17 December 1878, in which he points out that although Beethoven, in the Eroica and above all the Pastoral symphony, had created programme music:

It is Berlioz who must be considered the true founder of programme music, for every composition of his not only bears a specific title, but is furnished with a detailed explanation, a copy of which is supposed to be in the listener's hands during the performance.

- Letter 1105 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 12/24 February 1879, from Paris:

Yesterday I experienced great aesthetic pleasure. I heard the whole of Berlioz's Damnation de Faust — one of the wonders of art. There were moments when I was barely able to check the swell of tears which was choking me. The Devil knows, what a strange man this Berlioz was. On the whole, his musical nature tends to be antipathetic to me, and I just cannot reconcile myself to a certain ugliness in his harmony and modulations. But sometimes he attains incredible heights.

- Letter 1106 to Nadezhda von Meck, 12/24-13/25 February 1879, from Paris:

In general, I am far from being an unqualified admirer of Berlioz. In his musical organism there was some kind of deficiency; he lacked something as far as the skill of effectively choosing harmonies and modulations is concerned. In short, there is in his music an element of ugliness to which I just cannot reconcile myself. But this did not prevent him from possessing the soul of the loftiest and most sensitive artist, and sometimes he managed to reach unattainable heights. Some passages in Faust, in particular that staggeringly wonderful scene on the banks of the Elbe, belong to the pearls of his creative output. Yesterday, during that scene, I was barely able to check the sobs which were convulsing my throat. How delightful is Mephistopheles's recitative before he lulls Faust to sleep, and then the chorus of spirits and dance of sylphs which follows! When listening to this music one can feel how he who wrote it was seized with poetic inspiration, how he was profoundly stirred by the task at hand.

- Letter 1108 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 13/25 February 1879, from Paris:

On Sunday I had a tremendous musical treat. One of my favourite works was featured in Colonne's concert: Berlioz's [La damnation de] Faust. The performance was very good. I hadn't heard good music for such a long time that I was floating in seventh heaven. Another important factor contributing to this was that I was alone, without any familiar mugs sitting next to me. Still, what a work it is! Poor Berlioz! While he was alive, no one here wanted to have anything to do with him. Now in the newspapers he is apostrophized as 'the great Hector'...

- Letter 1346 to Nadezhda von Meck, 19 November/1 December–20 November/2 December 1879, when they were both in Paris at the same time:

Yesterday I was at one of Pasdeloup's concerts. It featured two acts from Berlioz's La prise de Troie. The public's enthusiasm was indescribable. Each number was applauded frenetically. These Frenchmen are amazing! Nowadays, whatever is played for them, as long as Berlioz's name is on the placard, will be received with equal enthusiasm. And yet, to be honest, La prise de Troie is a very poor and boring work. In it, more than anywhere else, are displayed all the most important defects of Berlioz, that is, melodic ugliness and poverty, overstrained harmonization, and the disparity between a rich fantasy and insufficient powers of invention. He had great intentions and a lofty spirit, but he lacked the strength to carry out his conceptions. [In a later section of this letter Tchaikovsky nevertheless urges Nadezhda von Meck to attend a concert conducted by Édouard Colonne which was also going to feature excerpts from La prise de Troie, and not to be put off by what he had said about Berlioz:] In the music of such a composer as Berlioz (an unhealthy and imperfect musician, but a poet of genius) one will always come across fine moments.

Views on Specific Works by Berlioz

In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles

- Les Francs juges, overture to the opera (1825–26) — see TH 277

- La damnation de Faust, Op. 24 (1845–46) — see TH 299

- Harold en Italie, symphony for viola and orchestra, Op. 46 (1834) — see TH 285

In Tchaikovsky's Letters

- Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14 (1830) — Letter 1115 to Nadezhda von Meck, 19 February/3 March–20 February/4 March 1879, after they had both heard the Symphonie at a concert in Paris:

It is with great interest that one listens to Berlioz's symphony. I would not say, though, that this is one of my favourite works. It has many anti-artistic effects, that is, of a purely external kind: for example, the depiction of thunder by means of kettledrums alone. But the Waltz and the March [to the Scaffold] are wonderful. As for the main theme, which runs through the whole symphony and depicts the beloved woman, why, surely you agree, my friend, that it is feeble! [5]

- La damnation de Faust, Op. 24 (1845–46) — see under "General observations" above; Letter 3830 to Vladimir Davydov, 29 March/10 April 1879, in which Tchaikovsky describes what he had been doing during his recent stay in Paris:

I heard, to my utmost delight, Berlioz's finest work, which never gets performed in our country: La Damnation de Faust. How I love this magnificent work, and how I wish that you could get to know it!

Bibliography

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 1 (1997), p. 263-264.

- ↑ See Unbekannter Čajkovskij. Entwürfe zu nicht ausgeführten Komponisten (1995), p. 283.

- ↑ From Vasily Yastrebtsev's reminiscences of Tchaikovsky (first published in 1899), cited here from Воспоминания о П. И. Чайковском (1979), p. 251; English translation in Tchaikovsky remembered (1993), p. 76.

- ↑ Herman Laroche's Foreword to Музыкальные фельетоны и заметки Петра Ильича Чайковского, 1868-1876 (1898); here cited from the German translation in P. Tschaikowsky. Musikalische Essays und Erinnerungen (2000), xliv.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky's benefactress, in contrast, was an unqualified admirer of Berlioz. On 19 February/3 March 1879, the day after the concert, she had written to the composer: "I liked the Berlioz symphony yesterday very much. How picturesquely it is composed! This man is able, with astonishing vividness, to convey by means of music everything that he wants, and he speaks through music and paints where it is required. What a delightful waltz at the ball, how fantastic the last movement is! One listens to it from beginning to end with ever keen interest; one may be exhausted by the duration but never by the music. A delightful composer!" Quoted from П. И. Чайковский. Переписка с Н. Ф. фон-Мекк, том 2 (1935), p. 61.