Letter 573 and Arthur Nikisch: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

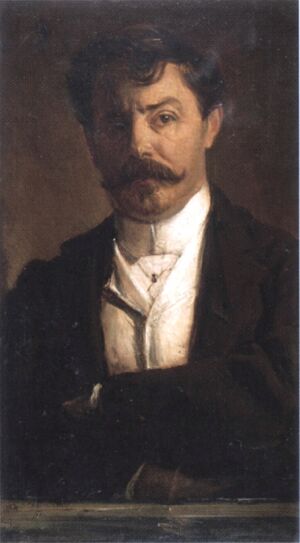

{{ | {{picture|file=Arthur Nikisch.jpg|caption='''Arthur Nikisch''' (1855-1922)<br/>Painted ca.1909 by Nikolaos Xidias (1826–1909)}} | ||

| | Hungarian conductor (b. 12 October 1855 at Lébényi Szent-Miklós; d. 23 January 1922 in [[Leipzig]]), born '''''Artúr Nikisch. | ||

| | |||

The son of a Moravian father and a Hungarian mother, he showed musical gifts at a very early age and was taught privately at first before enrolling at the [[Vienna]] Conservatoire, where he studied violin (under Josef Hellmesberger), piano, and composition. In 1874, Nikisch was engaged as a violinist by the [[Vienna]] Philharmonic and took part in the premiere of Anton Bruckner's Second Symphony on 20 February 1876, with the composer himself conducting. In the summer of 1876 he also played in the orchestra at the inaugural [[Bayreuth]] Festival. In 1878, Nikisch was appointed assistant conductor at the [[Leipzig]] Opera, rising to principal conductor the following year. | |||

==Tchaikovsky and Nikisch== | |||

[[Leipzig]] was one of the stops on Tchaikovsky's first concert tour of Western Europe in 1888, and it was there that he heard Nikisch conduct performances of two operas by [[Wagner]]: ''Das Rheingold'' and ''Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg''. The latter performance was staged specially at Tchaikovsky's request on 10 February 1888 {{NS}}, since he had never heard that opera before. In Chapter IX of his ''[[Autobiographical Account]]'' of this tour, Tchaikovsky would call Nikisch "a conductor of genius", describing the "magical" effect which he exerted over the orchestra. Tchaikovsky, as a member of the board of directors of the [[Moscow]] branch of the Russian Musical Society, invited Nikisch to give some concerts in [[Moscow]], and if it hadn't been for his departure for America in 1889, the Hungarian maestro would have come to Russia already in that year. (Tchaikovsky had hoped that his [[Piano Concerto No. 2]] would be premiered by [[Aleksandr Ziloti]] at a concert in [[Moscow]] conducted by Nikisch) <ref name="note1"/>. | |||

In 1889, Nikisch accepted the post of director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and during his four years in the United States he included several works by Tchaikovsky in the orchestra's concert programmes, including the first performance in America of the third (and definitive) version of the overture-fantasia ''[[Romeo and Juliet]]'' (at the Boston Music Hall on 7 February 1890) and the American premiere of the [[Concert Fantasia]] for piano with orchestra (at the [[New York]] Carnegie Hall on 12 January 1892, with Julie Rivé-King as the soloist). | |||

Nikisch returned to Europe in 1893 to take up an appointment as music director of the Budapest Opera, but two years later he was invited to become the principal conductor of both the [[Leipzig]] Gewandhaus orchestra and the [[Berlin]] Philharmonic (the latter at the instigation of the impresario [[Hermann Wolff]]). Nikisch accepted both posts, but toured mainly with the [[Berlin]] Philharmonic, including a notable tour of Russia in 1899 which covered [[Saint Petersburg]], [[Moscow]], [[Kiev]], [[Kharkov]], [[Odessa]], and [[Warsaw]] (which was then part of the Russian Empire). He also appeared frequently as a guest conductor with other major European orchestras, and it was in this capacity that he conducted the first performance in [[London]] of Tchaikovsky's [[Fifth Symphony]] on 29 June 1894 (the symphony's first performance in England had taken place a year earlier under Charles Hallé, in Manchester on 2 February 1893). Indeed, it was as a conductor of Tchaikovsky (and Bruckner) that Nikisch would make his mark. | |||

Nikisch's first concert in Russia took place in [[Moscow]] on 3/15 March 1895: he conducted the Russian Musical Society's orchestra in works by [[Wagner]], [[Saint-Saëns]], and [[Beethoven]], making a profound impression on the audience. He gave another concert in [[Moscow]] on 29 February/12 March 1896, and in the autumn of that year [[Modest Tchaikovsky]] invited him to come to [[Saint Petersburg]] for the first time to conduct the first concert for the newly-established Tchaikovsky Fund. This concert took place on 9/21 November 1896 and featured the [[Fifth Symphony]], the [[Piano Concerto No. 1]] (soloist [[Vasily Sapelnikov]]), the ''[[Romeo and Juliet]]'' overture, and the Finale from the [[Suite No. 3]]. It was the performance of the [[Fifth Symphony]] under Nikisch's baton at this concert that won Russian audiences over to this work, which had been received rather coldly at its premiere in 1888, when Tchaikovsky himself had conducted it. This historic concert was attended by [[Rimsky-Korsakov]], [[Taneyev]], [[Ippolitov-Ivanov]], and [[Rachmaninoff]], who were all greatly impressed by Nikisch's interpretation of the symphony. [[Ippolitov-Ivanov]] later recalled: | |||

{{quote|I had heard the [[Fifth Symphony]] many times, including a few times under the baton of Pyotr Ilyich, and I must confess that I didn't like it very much. I always remained indifferent to this work. On this occasion, too, I went to the concert with a somewhat prejudiced attitude, but from the very first notes I sensed that this would be something different, something that I had never heard before, and with each phrase, with each period I saw how there arose before my very eyes the edifice of a symphony which was completely new for me. What under Pyotr Ilyich's baton had come out as rather melancholic and soft acquired under Nikisch, by means of a specific tempo, resilience and rhythmic energy; he endowed the music with a cheerful mood, in spite of the minor key. His interpretation of the whole first movement was truly one of genius! <ref name="note2"/>}} | |||

Shortly after this concert [[Modest]] presented Nikisch with a fragment of the page in the ''[[Autobiographical Account of a Tour Abroad]]'' in which his late brother had described the Hungarian as a "conductor of genius". Nikisch thanked [[Modest]] in the following letter: | |||

{{quote|Dear friend and deeply esteemed [[Modest|Mr Tchaikovsky]]!}} | |||

{{quote|Accept my most profound and cordial gratitude for this invaluable present — a manuscript from your late brother's diary. You know the sincere inner piety which I feel towards his lofty genius, and how I regard it as my truly sacred mission to acquaint the world with his music in performances of the very highest quality. You can therefore understand the significance for me of that passage in his diary in which he, a great master, expresses such an exceptional recognition of my talent. And being in possession of just this part of the diary's manuscript is for me the greatest joy, a source of the greatest pride. It is to you, my dear friend, that I am indebted for this precious treasure! I shall of course preserve it like a holy relic" <ref name="note3"/>.}} | |||

Thanks to Nikisch the [[Fifth Symphony]] would become a staple in the repertoire of most European orchestras early in the twentieth century. | |||

At the end of 1897 Nikisch paid a second visit to [[Saint Petersburg]], again thanks to [[Modest]]'s initiative. On 13/25 December he conducted a concert to raise funds for a monument to Tchaikovsky. In the Russian part of the programme, apart from the [[Sixth Symphony]], [[Aleksandr Ziloti]] performed [[Rachmaninoff]]'s Piano Concerto No. 2. Nikisch also conducted the [[Sixth Symphony]] at a concert in [[Leipzig]] on 9/22 March 1900 which was held on the same day that [[Ziloti]] and [[Sapelnikov]] presented the Gewandhaus with a bust of Tchaikovsky. | |||

After the above-mentioned tour of Russia with the [[Berlin]] Philharmonic in 1899 Nikisch returned to Russia many times over the following years. For instance, in March 1902 he conducted works by Tchaikovsky, [[Glazunov]], and [[Rachmaninoff]] in [[Saint Petersburg]]; in May he gave two concerts in the imperial capital featuring works by [[Borodin]] and [[Rimsky-Korsakov]]; and in November he came to [[Saint Petersburg]] for the third time that year, to conduct [[Beethoven]]'s ''Missa Solemnis'' at a special concert to mark the [[Saint Petersburg]] Philharmonic Society's 100th anniversary ([[Beethoven]]'s Mass was chosen because it was at a concert of the Society in [[Saint Petersburg]] on 7/19 April 1824 that this great work had been given its world premiere). After the concert Nikisch was made an honorary member of the [[Saint Petersburg]] Philharmonic Society. In 1904 he undertook a second tour of Russia with the [[Berlin]] Philharmonic: on 10/23, 11/24, and 12/25 April they gave three concerts in [[Saint Petersburg]] in memory of Tchaikovsky, at which all six symphonies were performed, as were the overture-fantasia ''[[Hamlet (overture-fantasia)|Hamlet]]'', ''[[Francesca da Rimini]]'', and the [[Piano Concerto No. 2]] (soloist [[Sophie Menter]]). This cycle was a major event in the music life of the imperial capital. Nikisch's last visit to Russia took place in November 1913, and his concert programme was again devoted to Tchaikovsky. During World War I Nikisch remained in [[Leipzig]], where he continued to programme Tchaikovsky's works, even though some nationalistic newspapers accused him of neglecting the German masters and giving preference to Russian music. | |||

Arthur Nikisch also taught at the [[Leipzig]] Conservatory for a number of years and exerted a tremendous influence on the next generation of conductors, including Wilhelm Furtwängler. | |||

==External Links== | |||

* [[wikipedia:Arthur_Nikisch|Wikipedia]] | |||

==Bibliography== | |||

* {{bib|1960/61}} (1960) | |||

* {{bib|1994/35}} (1994) | |||

* {{bib|2006/18}} (2006) | |||

==Notes and References== | ==Notes and References== | ||

<references> | <references> | ||

<ref name="note1"> | <ref name="note1">See [[Aleksandr Ziloti]]'s letter to Tchaikovsky of 17 January 1889. Cited in L. M. Kutaleladze (ed.), {{und|Артур Никиш и русская музыкальная культура: Воспоминания, письма, статьи}} ([[Leningrad]], 1975), p. 19.</ref> | ||

<ref name="note2"> | <ref name="note2">[[Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov]], {{bib|1934/13|50 лет русской музыки в моих воспоминаниях}} (1934). Quoted here from {{und|Артур Никиш и русская музыкальная культура: Воспоминания, письма, статьи}} (1975), p. 26.</ref> | ||

<ref name="note3"> | <ref name="note3">Quoted from {{und|Артур Никиш и русская музыкальная культура: Воспоминания, письма, статьи}} (1975), p. 57.</ref> | ||

</references> | </references> | ||

[[Category:People|Nikisch, Artur]] | |||

[[Category:Conductors|Nikisch, Artur]] | |||

Revision as of 12:10, 27 November 2022

Hungarian conductor (b. 12 October 1855 at Lébényi Szent-Miklós; d. 23 January 1922 in Leipzig), born Artúr Nikisch.

The son of a Moravian father and a Hungarian mother, he showed musical gifts at a very early age and was taught privately at first before enrolling at the Vienna Conservatoire, where he studied violin (under Josef Hellmesberger), piano, and composition. In 1874, Nikisch was engaged as a violinist by the Vienna Philharmonic and took part in the premiere of Anton Bruckner's Second Symphony on 20 February 1876, with the composer himself conducting. In the summer of 1876 he also played in the orchestra at the inaugural Bayreuth Festival. In 1878, Nikisch was appointed assistant conductor at the Leipzig Opera, rising to principal conductor the following year.

Tchaikovsky and Nikisch

Leipzig was one of the stops on Tchaikovsky's first concert tour of Western Europe in 1888, and it was there that he heard Nikisch conduct performances of two operas by Wagner: Das Rheingold and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. The latter performance was staged specially at Tchaikovsky's request on 10 February 1888 [N.S.], since he had never heard that opera before. In Chapter IX of his Autobiographical Account of this tour, Tchaikovsky would call Nikisch "a conductor of genius", describing the "magical" effect which he exerted over the orchestra. Tchaikovsky, as a member of the board of directors of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society, invited Nikisch to give some concerts in Moscow, and if it hadn't been for his departure for America in 1889, the Hungarian maestro would have come to Russia already in that year. (Tchaikovsky had hoped that his Piano Concerto No. 2 would be premiered by Aleksandr Ziloti at a concert in Moscow conducted by Nikisch) [1].

In 1889, Nikisch accepted the post of director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and during his four years in the United States he included several works by Tchaikovsky in the orchestra's concert programmes, including the first performance in America of the third (and definitive) version of the overture-fantasia Romeo and Juliet (at the Boston Music Hall on 7 February 1890) and the American premiere of the Concert Fantasia for piano with orchestra (at the New York Carnegie Hall on 12 January 1892, with Julie Rivé-King as the soloist).

Nikisch returned to Europe in 1893 to take up an appointment as music director of the Budapest Opera, but two years later he was invited to become the principal conductor of both the Leipzig Gewandhaus orchestra and the Berlin Philharmonic (the latter at the instigation of the impresario Hermann Wolff). Nikisch accepted both posts, but toured mainly with the Berlin Philharmonic, including a notable tour of Russia in 1899 which covered Saint Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, Kharkov, Odessa, and Warsaw (which was then part of the Russian Empire). He also appeared frequently as a guest conductor with other major European orchestras, and it was in this capacity that he conducted the first performance in London of Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony on 29 June 1894 (the symphony's first performance in England had taken place a year earlier under Charles Hallé, in Manchester on 2 February 1893). Indeed, it was as a conductor of Tchaikovsky (and Bruckner) that Nikisch would make his mark.

Nikisch's first concert in Russia took place in Moscow on 3/15 March 1895: he conducted the Russian Musical Society's orchestra in works by Wagner, Saint-Saëns, and Beethoven, making a profound impression on the audience. He gave another concert in Moscow on 29 February/12 March 1896, and in the autumn of that year Modest Tchaikovsky invited him to come to Saint Petersburg for the first time to conduct the first concert for the newly-established Tchaikovsky Fund. This concert took place on 9/21 November 1896 and featured the Fifth Symphony, the Piano Concerto No. 1 (soloist Vasily Sapelnikov), the Romeo and Juliet overture, and the Finale from the Suite No. 3. It was the performance of the Fifth Symphony under Nikisch's baton at this concert that won Russian audiences over to this work, which had been received rather coldly at its premiere in 1888, when Tchaikovsky himself had conducted it. This historic concert was attended by Rimsky-Korsakov, Taneyev, Ippolitov-Ivanov, and Rachmaninoff, who were all greatly impressed by Nikisch's interpretation of the symphony. Ippolitov-Ivanov later recalled:

I had heard the Fifth Symphony many times, including a few times under the baton of Pyotr Ilyich, and I must confess that I didn't like it very much. I always remained indifferent to this work. On this occasion, too, I went to the concert with a somewhat prejudiced attitude, but from the very first notes I sensed that this would be something different, something that I had never heard before, and with each phrase, with each period I saw how there arose before my very eyes the edifice of a symphony which was completely new for me. What under Pyotr Ilyich's baton had come out as rather melancholic and soft acquired under Nikisch, by means of a specific tempo, resilience and rhythmic energy; he endowed the music with a cheerful mood, in spite of the minor key. His interpretation of the whole first movement was truly one of genius! [2]

Shortly after this concert Modest presented Nikisch with a fragment of the page in the Autobiographical Account of a Tour Abroad in which his late brother had described the Hungarian as a "conductor of genius". Nikisch thanked Modest in the following letter:

Dear friend and deeply esteemed Mr Tchaikovsky!

Accept my most profound and cordial gratitude for this invaluable present — a manuscript from your late brother's diary. You know the sincere inner piety which I feel towards his lofty genius, and how I regard it as my truly sacred mission to acquaint the world with his music in performances of the very highest quality. You can therefore understand the significance for me of that passage in his diary in which he, a great master, expresses such an exceptional recognition of my talent. And being in possession of just this part of the diary's manuscript is for me the greatest joy, a source of the greatest pride. It is to you, my dear friend, that I am indebted for this precious treasure! I shall of course preserve it like a holy relic" [3].

Thanks to Nikisch the Fifth Symphony would become a staple in the repertoire of most European orchestras early in the twentieth century.

At the end of 1897 Nikisch paid a second visit to Saint Petersburg, again thanks to Modest's initiative. On 13/25 December he conducted a concert to raise funds for a monument to Tchaikovsky. In the Russian part of the programme, apart from the Sixth Symphony, Aleksandr Ziloti performed Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2. Nikisch also conducted the Sixth Symphony at a concert in Leipzig on 9/22 March 1900 which was held on the same day that Ziloti and Sapelnikov presented the Gewandhaus with a bust of Tchaikovsky.

After the above-mentioned tour of Russia with the Berlin Philharmonic in 1899 Nikisch returned to Russia many times over the following years. For instance, in March 1902 he conducted works by Tchaikovsky, Glazunov, and Rachmaninoff in Saint Petersburg; in May he gave two concerts in the imperial capital featuring works by Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov; and in November he came to Saint Petersburg for the third time that year, to conduct Beethoven's Missa Solemnis at a special concert to mark the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Society's 100th anniversary (Beethoven's Mass was chosen because it was at a concert of the Society in Saint Petersburg on 7/19 April 1824 that this great work had been given its world premiere). After the concert Nikisch was made an honorary member of the Saint Petersburg Philharmonic Society. In 1904 he undertook a second tour of Russia with the Berlin Philharmonic: on 10/23, 11/24, and 12/25 April they gave three concerts in Saint Petersburg in memory of Tchaikovsky, at which all six symphonies were performed, as were the overture-fantasia Hamlet, Francesca da Rimini, and the Piano Concerto No. 2 (soloist Sophie Menter). This cycle was a major event in the music life of the imperial capital. Nikisch's last visit to Russia took place in November 1913, and his concert programme was again devoted to Tchaikovsky. During World War I Nikisch remained in Leipzig, where he continued to programme Tchaikovsky's works, even though some nationalistic newspapers accused him of neglecting the German masters and giving preference to Russian music.

Arthur Nikisch also taught at the Leipzig Conservatory for a number of years and exerted a tremendous influence on the next generation of conductors, including Wilhelm Furtwängler.

External Links

Bibliography

- Зарубежные встречи Чайковского (1960)

- Die Rettung der Fünften Sinfonie Tschaikowskys durch Arthur Nikisch (1994)

- An Tschaikowsky scheiden sich die Geister. Textzeugnisse der Čajkovskij-Rezeption, 1866-2004 (2006)

Notes and References

- ↑ See Aleksandr Ziloti's letter to Tchaikovsky of 17 January 1889. Cited in L. M. Kutaleladze (ed.), Артур Никиш и русская музыкальная культура: Воспоминания, письма, статьи (Leningrad, 1975), p. 19.

- ↑ Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov, 50 лет русской музыки в моих воспоминаниях (1934). Quoted here from Артур Никиш и русская музыкальная культура: Воспоминания, письма, статьи (1975), p. 26.

- ↑ Quoted from Артур Никиш и русская музыкальная культура: Воспоминания, письма, статьи (1975), p. 57.