Sergei Rachmaninoff

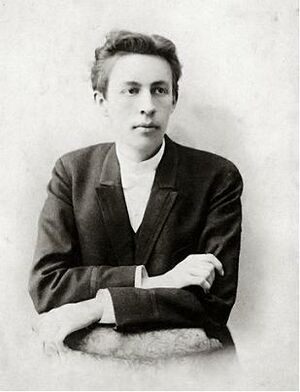

Russian composer, pianist, and conductor (b. 20 March/1 April 1873 in Semyonovo, near Veliky Novgorod; d. 28 March 1943 in Beverley Hills, California), born Sergey Vasilyevich Rakhmaninov (Сергей Васильевич Рахманинов), but after emigrating from Russia he adopted the spelling Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Early Life

Sergei was the son of Vasily Rakhmaninov (1841–1916) and his wife Lyubov Petrovna (b. Butakova, 1853–1929). The elder sister of Sergei's father, Yuliya Arkadyevna Rakhmaninova (1835–1925) was married to Ilya Ziloti (d.1900), with whom she had four children, of which the second oldest, born in 1863, was the future pianist and conductor Aleksandr Ziloti. Thus Sergei and Aleksandr were first cousins. Sergei showed musical gifts at a very early age and started having formal lessons when he was five.

Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff

The Rakhmaninov family eventually moved to Saint Petersburg, and Sergei enrolled at the Conservatory in 1883, aged ten. Due to academic failure in his general subject classes in 1885, it was decided that Sergei should move to Moscow and study with Nikolay Zverev (1833–1893), a private piano teacher who numbered Mily Balakirev among his former students. Sergei became a boarder in Zverev's house, where he saw Tchaikovsky for the first time at one of the musical soirées organized by his teacher. In the autumn of 1885, Sergei also became a student at the Moscow Conservatory. In the spring of 1888, he was admitted into the piano class taught by his cousin Aleksandr Ziloti, as well as into the composition, instrumentation, and harmony class of Anton Arensky. Rachmaninoff also began studying advanced counterpoint with Sergey Taneyev, on the recommendation of Tchaikovsky, who as a member of the Conservatory's examining board had been very impressed by the young student's performance in the theory exams that year. Tchaikovsky is reported as having said about the 16-year-old Rachmaninoff: "For him I predict a great future" [1]. The classes with Taneyev encouraged him to devote himself to composition in earnest.

Shortly after the premiere of The Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg on 3/15 January 1890, Tchaikovsky discussed with his publisher Pyotr Jurgenson the possibility of commissioning a piano arrangement of his ballet for four hands (his former student Ziloti had made a transcription of The Sleeping Beauty for piano solo, which was published at the end of 1889, but Tchaikovsky evidently felt that only a more sophisticated arrangement could do justice to his music for this ballet). The commission was eventually given to the 18-year-old Rachmaninoff in 1891 [2]. Perhaps Tchaikovsky was aware of the fact that in 1886 Sergei had made a piano duet arrangement of his Manfred symphony (unfortunately this arrangement seems to have been lost), and this prompted him (or Jurgenson) to entrust The Sleeping Beauty to this highly gifted student. However, Tchaikovsky was disappointed by the young man's work: as he explained in a letter to Ziloti, he felt that Rachmaninoff's arrangement of the ballet was "absolutely lacking in courage, initiative and creativity!!!" and further lamented: "I wanted the ballet to be arranged for four hands so that it might be rendered as seriously and skilfully as an arrangement of a symphony. Alas, this is impossible; what has been done cannot be undone; but at least it will be an improvement on what we have now" [3]. Still, Rachmaninoff's piano duet arrangement of The Sleeping Beauty was published in October 1891. Towards the end of his life (1941), Rachmaninoff also made a piano transcription of Tchaikovsky's Cradle Song (Колыбельная песня) — No. 1 of the Six Romances, Op. 16 (TH 95).

In the autumn of 1891, Taneyev started working on a piano reduction of Iolanta, and Tchaikovsky wrote to him on 25 October/6 November, giving some further explanations. In this letter Tchaikovsky also added a footnote: "On Monday Ziloti will invite you to come and listen to Rachmaninoff's concerto" [4]. The work Tchaikovsky is referring to is the Piano Concerto No. 1 in F-sharp minor, which Rachmaninoff had started writing in March 1891, taking Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto as his model. Rachmaninoff eventually completed his concerto in 1892, and it was published as his Op. 1 that year. Although Rachmaninoff would subsequently revise this youthful work in 1917, it never became as popular as his world-famous Second and Third Piano Concertos (completed in 1901 and 1909 respectively). Unfortunately, it is not known what Tchaikovsky thought of this early work by Rachmaninoff or if he even had a chance to hear all of it.

Although Rachmaninoff wrote a number of orchestral and chamber music pieces during his last year at the Moscow Conservatory (1891–92), his most important work from that period, and the one which would attract Tchaikovsky's attention, was the one-act opera Aleko (Алеко). This setting of Pushkin's 1824 poem The Gypsies (Цыганы) was not in fact Rachmaninoff's own idea, as it was a graduation exercise which he and two other students (including Lev Konyus) had been set by the Conservatory's board of examiners in March 1892. The libretto was provided by the theatre critic and playwright Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, future co-founder (in 1898) of the Moscow Art Theatre. It seems very likely that both Nemirovich-Danchenko, in his treatment of Pushkin's poem — which deals with how a nobleman Aleko decides to join a group of gypsies in his search for a simpler way of life but ultimately murders his beloved, the gypsy girl Zemfira, out of jealousy — and Rachmaninoff, in his enthusiasm for the subject, were inspired by Pietro Mascagni's Cavalleria rusticana (1890), itself a one-act opera with jealousy as one of its principal motifs [5]. This first masterpiece of Italian verismo had already been staged at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1891, but was revived again in March 1892, just as Rachmaninoff started work on his graduation piece. He completed Aleko in just 19 days, and on 7/19 May 1892 the examiners' commission decided to award him the Great Gold Medal (which had only been awarded on two earlier occasions in the Conservatory's history — to Taneyev and Arseny Koreshchenko). Some excerpts from Aleko were performed at the Conservatory's graduation gala on 31 May/12 June 1892. Tchaikovsky was not in Moscow on either of those occasions, but as a member of the examiners' commission he must have seen the score of the opera at some point, and, according to Rachmaninoff's memoirs, it was he who recommended to the Imperial Theatres' Directorate that they should stage Aleko at the Bolshoi Theatre during the following season [6]. It is interesting that Tchaikovsky himself had been drawn to Pushkin's poem in his youth: in the 1860s, he composed Zemfira's Song (TH 90), a setting of the gypsy girls defiant song "Old husband, stern husband" (Старый муж, грозный муж) from The Gypsies — verses which were also set to music by Pauline Viardot around 1874, very likely following a suggestion from Ivan Turgenev, who venerated Pushkin.

On 6 December 1892 [O.S.], the same day that both Iolanta andThe Nutcracker had their premiere at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, one of the city's newspapers published an interview with Tchaikovsky, entitled With the Author of "Iolanta" (TH 325). Amongst other things, Tchaikovsky said that he hoped to be able to carry on composing for some five more years, but that as soon as he saw that his inspiration was drying up he would retire and "make way for younger people". When the reporter asked him if he was thinking of anyone in particular, Tchaikovsky replied: "In Russia today we have many talented young composers... Here in Saint Petersburg there's Glazunov, whilst over in Moscow we have Arensky, Davydov (a nephew of our famous cellist) and Rachmaninoff, who has created a wonderful opera setting of Pushkin's poem The Gypsies..." [7]. Rachmaninoff read this interview and a few days afterwards commented on it in a letter to a friend: "Tchaikovsky said [in this interview] that he would have to stop composing eventually and make way for younger people. When the reporter asked him if there really were any such young talents, Tchaikovsky answered in the affirmative and mentioned Glazunov for Saint Petersburg and me and Arensky for Moscow. That made me so glad! My hearty thanks to the old man for not having forgotten about me!" [8].

On 27 February/11 March 1893, during a visit by Tchaikovsky to Moscow, Rachmaninoff presented him with an inscribed copy of his Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op. 3, a set of five piano solo pieces of which No. 2 is the Prelude in C-sharp♯ minor, which would later become famous around the whole world [9]. Tchaikovsky especially liked the Prelude and the Melody in E major (No. 3 of the Morceaux) [10].

A few months earlier (in 1892) Rachmaninoff had, through Ziloti, asked Modest Tchaikovsky, the composer's brother, to provide him with a libretto for an opera Undina, based on Vasily Zhukovsky's verse translation (1837) of the Romantic German novella about a water spirit who gains a soul when she falls in love with a knight, but subsequently causes his perdition. Now Tchaikovsky himself had been fascinated by Zhukovsky's rendering of this story ever since his youth, and in 1869 he wrote an opera Undina (TH 2). It was rejected by the Imperial Theatres' Directorate, however, and Tchaikovsky burnt the score in 1875, although he did use some of its music for Act II of Swan Lake. In April–May 1878, after re-reading the tale, he again considered writing an opera Undina (TH 214) and asked his brother Modest to compile a scenario for him. The project was dropped very soon, though. In 1886, Tchaikovsky returned to the subject yet again with a view to creating a ballet Undina (TH 226), but abandoned the idea when he started working on The Sleeping Beauty instead. As mentioned above, Modest Tchaikovsky agreed, in 1892, to provide Rachmaninoff with a scenario for an opera Undina, but it seems that he suddenly remembered his elder brother's fondness for the story of Undina, since in April 1893, instead of sending the completed scenario to Rachmaninoff, he sent it to Tchaikovsky, asking if he wanted to take up the subject again and write an opera on it [11]. Tchaikovsky, however, replied on 17/29 April 1893:

For God's sake, do try to find me, or devise yourself, a subject that isn't fantastic — something like Carmen and Cavalleria rusticana. Now don't you think you've done enough with the scenario as it is? Do you really have to write verses for Rachmaninoff? Why not simply let someone else versify your scenario for him. Please, my dear fellow, don't be angry with me and don't feel upset. [...] I'll send the scenario to Rachmaninoff" [12].

Rachmaninoff duly received the Undina scenario and was sufficiently pleased with the idea that in October 1893 he wrote to Modest Tchaikovsky, asking him for more material. But the projected opera was soon abandoned [13]. Some years later Rachmaninoff did manage to secure Modest Tchaikovsky as his librettist for the opera Francesca da Rimini, which was premiered at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow in 1906, but it was not well received.

Returning to April 1893, though: preparations were now underway at the Bolshoi Theatre for the staging of Aleko, thanks in no small part to Tchaikovsky's endorsement. The premiere of the opera was scheduled for late April/early May, and from a letter to his brother Modest we know that Tchaikovsky was very keen to attend this before heading off for England to collect his Honorary Doctorate from the University of Cambridge in June [14]. Fortunately, Tchaikovsky was able to make it to the premiere of Aleko at the Moscow Bolshoi Theatre on 27 April/9 May 1893, conducted by Ippolit Altani and featuring the distinguished bass Bogomir Korsov in the title role. Like the rest of the audience that evening, Tchaikovsky applauded enthusiastically at the end of the performance, and, as Rachmaninoff later recalled, he had suggested to the younger composer that Aleko should be performed together with Iolanta as a double-bill at the Bolshoi Theatre [15]. If this idea had worked out, it might have provided Russia with her very own counterpart to the famous pairing of Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci (which were not in fact shown together until 22 December 1893 in Rome). Tchaikovsky admired Mascagni's opera (which he first heard in Warsaw on 1/13 January 1892), but he did not have an opportunity of hearing Ruggiero Leoncavallo's Pagliacci (first staged in Milan on 21 May 1892). In contrast to these two verismo operas, Iolanta and Aleko would probably have been rather mismatched, but it is interesting that Tchaikovsky made such a suggestion in the first place. One reason why Aleko appealed to him so much may have been that, like Cavalleria rusticana, it was so different to Wagner's long operas with their "Wotans, Brünnhildes, and Fafners" (see the 1892 interview A Conversation with P. I. Tchaikovsky). A few days after the premiere of Aleko, Tchaikovsky commented on it in a letter to Ilya Slatin: "I liked this delightful work very much" [16]. It seems that there were indeed plans to pair Aleko with Iolanta at the Bolshoi Theatre (where Tchaikovsky's last opera had not yet been performed), but such a double-bill, Rachmaninoff and Tchaikovsky were informed by the management, would not be possible until December 1893. Tchaikovsky's death on 25 October/6 November put an end to these plans. Iolanta did, however, receive its first performance in Moscow a few weeks later, on 11/23 November 1893: it was paired that evening not with Aleko, but with Leoncavallo's Pagliacci [17].

The premiere of Aleko on 27 April/9 May 1893 had also been attended by Ivan Vsevolozhsky, the director of the Imperial Theatres in Saint Petersburg, and he was so impressed that he wanted Rachmaninoff to write a new opera for the Mariinsky Theatre. However, nothing came of this project, and meanwhile the fortunes of Aleko also experienced an unexpected setback: after its premiere Rachmaninoff's first opera was performed just one more time (on 29 April/11 May) before the Bolshoi Theatre closed down for the summer. When the new season began in September, Aleko was not included in the repertoire, and in fact it would not be staged in Moscow again until 1905, now with Feodor Chaliapin in the title role.

On 18/30 September 1893, there was a musical soirée in Taneyev's flat in Moscow at which Tchaikovsky's own piano duet arrangement of the Sixth Symphony was played through in the presence of the author by Taneyev himself and Lev Konyus. Tchaikovsky was not satisfied with his work and kept interrupting the two pianists to correct this or that detail. The young Rachmaninoff had also been invited to play some of his latest compositions: the Suite No. 1 for two pianos, Op. 5, and the orchestral fantasia The Rock (Утёс), Op. 7. Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov, who was also present on that occasion, later recalled the favourable impression which these works had made on Tchaikovsky: "At the end of the evening Rachmaninoff acquainted us with a symphonic poem he had just completed: The Rock, based on a poem by Lermontov and undoubtedly written under the influence of N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov. The symphonic poem went down very well with everyone, especially with Pyotr Ilyich, who was fascinated by its colouring. This performance of The Rock and the ensuing discussion helped to take Pyotr Ilyich's mind off the symphony and restored him to his previous agreeable mood" [18].

Rachmaninoff himself would later recall this evening in a letter: "I remember very well how in October [sic] of that very same year [1893] I met P. I. Tchaikovsky for the last time; I played him The Rock, and he said with that nice grin of his: 'It's amazing how many things Serezha has managed to write this summer! A symphonic poem, a concerto, a suite, etc etc! All I've managed to write is just this one symphony!' This symphony was his sixth and last" [19]. Rachmaninoff had initially hoped to attend the premiere of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6 in Saint Petersburg on 16/28 October 1893, but in the end he travelled to Kiev to conduct some performances of Aleko there.

The sad news of Tchaikovsky's death prompted Rachmaninoff to write a piano trio dedicated to the memory of Russia's most beloved composer (just as Tchaikovsky himself had dedicated his Piano Trio "to the memory of a great artist", his friend and mentor Nikolay Rubinstein). Rachmaninoff completed his Trio élégiaque No. 2 in D minor, Op. 9, on 15/27 December 1893.

In 1904, Rachmaninoff accepted an offer to conduct at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, and although his tenure was not very long (it ended with his resignation in 1906), he conducted many works by Tchaikovsky, including Yevgeny Onegin, The Oprichnik, and The Queen of Spades, as well as his three ballets. At the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg he directed six performances of his favourite Tchaikovsky opera The Queen of Spades in 1912. As the conductor at several concerts of the Russian Musical Society in Moscow during those years, Rachmaninoff gained wide acclaim for his interpretations, in particular, of Tchaikovsky's Fourth, Fifth and Sixth symphonies, and the orchestral fantasias Francesca da Rimini and The Tempest.

After Rachmaninoff emigrated from Russia with his young family in December 1917, he was forced to set aside his creative work to some extent in order to concentrate on his many appearances as a concert pianist in Europe and America. One of his calling-cards was Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1, which he had also played many times in Russia. Rachmaninoff also recorded several piano pieces by Tchaikovsky for the gramophone, including On the Troika: November — No. 11 of The Seasons — in 1928. The Senar website (in Russian), named after the composer's Villa Senar in Switzerland, has a section featuring Rachmaninoff's recordings, including these pieces by Tchaikovsky.

In a memoir written in 1930, Rachmaninoff recalled the generous encouragement he had received from Tchaikovsky at the time of Aleko and paid tribute to his character: "Tchaikovsky was already renowned then, he was recognized all over the world and revered by everyone, but fame had not spoilt him. Of all the people and artists whom I have had occasion to meet, Tchaikovsky was the most enchanting. His delicacy of spirit was unique. He was modest like all truly great men and simple as only very few are. Of all those I have known, only Chekhov was like him" [20].

Bibliography

- Чайковский и Рахманинов (1923)

- Письмо из Парижа. Четвертый концерт Рахманинова (1927)

- Воспоминания (1978)

- Начало одной творческой дружбы (1978)

- Tschaikowsky und meine Oper Aleko (1994)

- Инструментальная кантиленная мелодика и её стилистические преломления в русской музыке конца ХIХ- начала ХХ веков (Чайковский, Танеев, Рахманинов, Скрябин) (2001)

- Русская музыка конца XIX - начала XX века. П. Чайковский, А. Скрябин, С. Рахманинов (2004)

- Рукопись в структуре творческого процесса. Очерки музыкальной текстологии и психологии творчества (2009)

- Сумщина в долях трьох геніїв (2014)

- Переложение балета «Спящая красавица» для фортепиано в 4 руки. Чайковский, Зилоти, Рахаманинов (2014)

External Links

- Wikipedia

- Internet Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- VIAF

- Senar (Russian internet resource on the life and works of Rachmaninoff)

Notes and References

- ↑ Quoted in M. Harrison, Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings (2005), p. 21.

- ↑ See also M. Harrison, Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings (2005), p. 18.

- ↑ Letter 4405 to Aleksandr Ziloti, 14/26 June 1891.

- ↑ Letter 4525 to Sergey Taneyev, 25 October/6 November 1891.

- ↑ See also M. Harrison, Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings (2005), p. 40.

- ↑ See also the extract from Sergei Rachmaninoff's memoirs (1978), which is included (in German translation) in Tschaikowsky aus der Nähe. Kritische Würdigungen und Erinnerungen von Zeitgenossen (1994), p. 111–112.

- ↑ The interview With the Author of "Iolanta" is included (in German) in Tschaikowsky aus der Nähe. Kritische Würdigungen und Erinnerungen von Zeitgenossen (1994), p. 229–231. It seems that the suspension points occur in the original Russian text of this interview as published by the Petersburg Gazette (Петербургская газета) in 1892.

- ↑ Letter from Sergei Rachmaninoff to his friend, the singer Mikhail Slonov, 14/26 December 1892. Quoted in Tschaikowsky aus der Nähe. Kritische Würdigungen und Erinnerungen von Zeitgenossen (1994), p. 230 (note 502).

- ↑ See also Дни и годы П. И. Чайковского. Летопись жизни и творчества (1940), p. 576.

- ↑ M. Harrison, Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings (2005), p. 49.

- ↑ Modest Tchaikovsky explains this himself in his biography of the composer Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1997), p. 542 (footnote).

- ↑ Letter 4919 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 17/29 April 1893.

- ↑ M. Harrison, Rachmaninoff: Life, Works, Recordings (2005), p. 50.

- ↑ See also Letter 4921 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 22 April/4 May–23 April/5 May 1893, in which Tchaikovsky discusses his travel plans and mentions the date of the premiere of Aleko.

- ↑ See also the extract from Sergei Rachmaninoff's memoirs (1978), which is included (in German translation) in Tschaikowsky aus der Nähe. Kritische Würdigungen und Erinnerungen von Zeitgenossen (1994), p. 111–112.

- ↑ Letter 4926 to Ilya Slatin, 3/15 May 1893.

- ↑ See also the extract from Sergei Rachmaninoff's memoirs (1978), which is included (in German translation) in Tschaikowsky aus der Nähe. Kritische Würdigungen und Erinnerungen von Zeitgenossen (1994), p. 111–112; and also Ernst Kuhn's note on p. 112 (note 266).

- ↑ Extracts from 50 лет русской музыки в моих воспоминаниях (1934) are included in Воспоминания о П. И. Чайковском (1980), p. 233–240 (239). The extract referring to this soirée is also included in Tchaikovsky remembered (1993), p. 198–199.

- ↑ Letter from Sergei Rachmaninoff to Boris Asafyev, 13/26 April 1917. Quoted in the notes for Воспоминания о П. И. Чайковском (1980), p. 404.

- ↑ Sergei Rachmaninoff, 'Difficult moments of my career' (Трудные моменты моей деятельности). The extract on Tchaikovsky from this essay is quoted in Пётр Ильич Чайковский, 1840-1893 (1986), under the photograph of Rachmaninoff towards the end of the book. The whole essay is also available online (in Russian) at the Senar website on the life and works of Rachmaninoff.