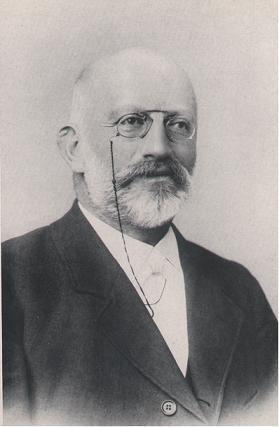

Hermann Wolff

German concert agent, journalist, and impresario (b. 4 September 1845 [N.S.] in Cologne; d. 3 February 1902 [N.S.] in Berlin).

Biography

The Wolff family was of Jewish ancestry and had lived in the Rhineland for many generations. In 1855, Hermann's father, a businessman, decided to move with his whole family to Berlin. Hermann was trained to follow his father into business, but his real passion had always been music and he was allowed to study the piano and music theory in his spare time. In order to supplement his income as a trader at the Berlin Stock Exchange he began writing newspaper articles. When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870 Wolff was called up and, because he was fluent in French, he was detailed as an interpreter for an army doctor treating wounded prisoners of war.

An early admirer of Wagner's music, Wolff travelled to Bayreuth in 1872 to attend the laying of the foundation stone of the new Festival Theatre. While still continuing to do business on the Berlin Stock Exchange in the mornings, Wolff began to work for the music publishing firm of Bote & Bock. His new job involved gathering musical news from English, German, French, and Italian newspapers and condensing these into brief summaries. In 1875 he met the young Austrian-born actress Louise Schwarz (1855–1935), and they were married three years later. They had two daughters, Edith and Lili, and a son, Werner, who became a conductor.

During one of his visits to Berlin in 1880, Anton Rubinstein happened to tell Hugo Bock (the head of Bote & Bock, who were the publishers of his works in Germany) that he was looking for a reliable assistant to organize his forthcoming concert tour to Spain and Portugal. Bock recommended Wolff, and the latter travelled to Spain in December to familiarize himself with the local conditions. Rubinstein's tour of Spain began in January 1881 and took him and Wolff, who acted as his manager and press secretary, to the following cities: Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Toledo, Seville, Cordoba, Granada, Jerez, and Cadiz. Spanish audiences were not well versed in the classical repertoire, but they welcomed the great pianist with open arms and styled him "Don Antonio". Rubinstein was greatly impressed by Wolff's efforts and invited him to accompany him on his tour of Great Britain that summer.

Already before travelling to Spain with Rubinstein, Wolff had started to offer his services to other musicians (such as Sophie Menter), carrying out negotiations on their behalf with concert hall managers in various countries. Then, in 1880, he set up his own agency in Berlin, the "Concert Direction Hermann Wolff". Its activities included organizing concerts on behalf of musicians, or on Wolff's own initiative, as well as securing engagements for them. Very soon such venerable societies as the Leipzig Gewandhaus and the Frankfurt Museumsgesellschaft were enlisting the services of Wolff's agency to engage guest soloists and conductors, attracted by his wide-ranging international contacts. Because the firm's telegraphic address was MUSIKWOLFF-BERLIN, its founder was given the nickname of "Musikwolff". There was nothing rapacious about his business dealings, though, as he generously supported both established and upcoming artists and was willing to take risks for them.

In 1882, when the members of Benjamin Bilse's orchestra in Berlin (an ensemble whose concerts were very popular and had often featured Tchaikovsky's works) fell out with their conductor, Wolff stepped in and reorganized the players under the new name of "Philharmonic Orchestra". The orchestra's first conductors, among them Karl Klindworth, were unable to attract sufficiently large audiences, however, and the Berlin Philharmonic Society decided to dissolve itself in 1887. Wolff again intervened to save the orchestra, taking over its financial management. Most importantly, he got in touch with Hans von Bülow (whom he had known since 1880, when he organized his recital tour to Scandinavia) and persuaded him to accept the post of principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. Bülow's first concert with the orchestra, on 21 October 1887, heralded the swift rise of Berlin to become the most important music centre in Germany (surpassing Leipzig). Wolff played a vital role in this, thanks to his association with Bülow and his enterprising spirit. Thus, he had a new concert venue built in Berlin: the Bechstein Hall, which was designed for chamber music concerts and solo recitals. The hall was inaugurated in October 1892 with a series of recitals given in the course of that month by Bülow, Brahms with the Joachim Quartet, and Rubinstein.

Tchaikovsky met Hermann and Louise Wolff in Berlin in January 1888 during his first concert tour to Western Europe. He enjoyed their warm hospitality on this and subsequent visits to the German capital. Wolff's daughter Edith later recalled that meeting Tchaikovsky was for her father "one of the most interesting encounters of his life, which was so rich in acquaintances with individuals of genius. My mother said of Tchaikovsky, when he visited her in Berlin soon afterwards, that he was the most delightful and charming guest she had ever welcomed to her house" . Wolff and his associate Hermann Fernow organized Tchaikovsky's concert tours of Germany, Switzerland and America during the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Hans von Bülow's death in 1894 was a bitter blow for Wolff, but he rallied his spirits and set about looking for someone worthy of succeeding Bülow at the helm of the Berlin Philharmonic. This was to be Arthur Nikisch, whose first concert with the orchestra, on 14 October 1895, featured Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5, a work that Nikisch was championing across Europe. Wolff organized the Berlin Philharmonic's tours under Nikisch to Russia, Spain, Portugal, Belgium, Switzerland, and France. In 1896, Emperor Wilhelm II appointed Wolff to head the delegation of German musicians who attended the coronation festivities in Moscow for Nicholas II, the new Tsar of Russia.

Many renowned composers and musicians visited Hermann and Louise Wolff's house in Berlin, especially in conjunction with the so-called "Philharmonic dinners" given there on Sunday afternoons after rehearsals with the Philharmonic Orchestra. In some cases these musicians became close friends of the family. Apart from Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky, another notable guest was Brahms, who once sang his Wiegenlied for little Edith.

Hermann Wolff died on 3 February 1902, aged just fifty-six. All the leading German newspapers hastened to pay tribute to his untiring efforts in turning Berlin into one of the music capitals of the world. Nikisch conducted the Philharmonic Orchestra at a concert held in his memory.

Legacy

After Wolff's death, his widow Louise took charge of the concert agency, and she was soon popularly known as "Königin Louise" (in allusion to the beloved Queen of Prussia during the Napoleonic Wars) because of the way she dominated music life in Berlin. She continued her husband's close collaboration with Nikisch and the Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as inviting many foreign artists, including Rachmaninoff and Chaliapin, to perform in Berlin. When her loyal assistant Hermann Fernow died in 1917, Louise had to look for a new associate and eventually chose Erich Sachs, the owner of a smaller concert agency. A merger took place, and the firm was now known as the "Concert Direction Wolff & Sachs", although Louise continued to exercise sole responsibility for the Berlin Philharmonic's concerts. After Nikisch's death in 1923, she established a good relationship with his young successor, Wilhelm Furtwängler, with whom she jointly drew up the orchestra's programmes. One highlight of Louise's last years was her organization of Yehudi Menuhin's triumphant début in Berlin on 12 April 1929, a few days before the boy's thirteenth birthday.

Very soon after Hitler came to power in January 1933 it became clear that the days of the concert agency founded by Hermann Wolff were numbered. Thus, the Nazi government prohibited Bruno Walter from conducting a scheduled concert with the Berlin Philharmonic. By the end of 1934 Louise had decided to dissolve the agency, since she realised that her daughters, Edith and Lili, on account of their Jewish ancestry, would not be allowed to carry on their work for the family firm undisturbed. When she announced her decision in April 1935, many famous musicians wrote to Louise to express their sadness over the loss of this institution. A few weeks later, on 25 June 1935, Louise herself died.

Edith and Lili still remained proprietors of the Bechstein Hall built by their father, but the Nazis forced them to remove the busts of Anton Rubinstein and Josef Joachim from the foyer (they had been erected there by Hermann Wolff alongside those of Bülow and Brahms, to commemorate the four great musicians who inaugurated the concert-hall in 1892). Detectives sent by the Reichsmusikkammer ransacked the offices of Edith and Lili in 1936 and carried away many valuable documents (letters, autographs, programme notes) in which the whole fruitful history of the Concert Direction Hermann Wolff was reflected. In 1942, Edith was interned in the concentration camp of Theresienstadt (Terezín), but, unlike some of her friends who were later deported to Auschwitz, she survived the war.

In 1954, Edith published a very interesting book — Wegbereiter großer Musiker (Path-breakers for Great Musicians) — in which she gave an account of the activities of her father's concert agency, replete with lively anecdotes about the composers and musicians whom her parents had worked with.

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

3 letters from Tchaikovsky to Hermann Wolff have survived, dating from 1889 and 1891, all of which have been translated into English on this website:

- Letter 3754a – 5/17 January 1889, from Frolovskoye

- Letter 3785 – 5/17 February 1889, from Dresden

- Letter 4381a – 6/18 May 1891, from Philadelphia

39 letters from Hermann Wolff to Tchaikovsky, dating from 1887 to 1891, are preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin (a4, Nos. 426–464).

Bibliography

- Stargardt-Wolff, E. Wegbereiter großer Musiker (Berlin / Wiesbaden: Bote & Bock, 1954)

- Čajkovskij et la France. À propos de quelques lettres de Čajkovskij à Félix Mackar (1968)

- Paris vaut bien une messe! Bisher unbekannte Briefe, Notenautographie und andere Čajkovskij-Funde (1998)

- Zwei neu aufgetauchte Briefe Čajkovskijs an Hermann Wolff und Franz Schäffer aus dem Jahr 1889 (2012)

- Čajkovskij und die Konzertagentur Hermann Wolff. Sozialhistorische und biographische Perspektiven. Teil 1 (2023)