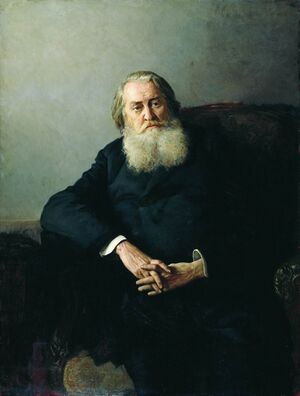

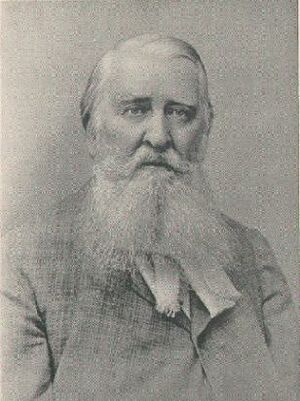

Aleksey Pleshcheyev

Russian poet and translator (b. 22 November/4 December 1825 in Kostroma; d. 8 October 1893 [N.S.] in Paris), born Aleksey Nikolayevich Pleshcheyev (Алексей Николаевич Плещеев).

Biography

Born into a gentry family, Aleksey spent his childhood in Nizhny Novgorod and enjoyed a good education at home. In 1839, he was sent to the School of Guard Ensigns in Saint Petersburg, but he disliked the atmosphere there and left after a year and a half. He eventually enrolled at the Oriental Faculty of Saint Petersburg University in 1843. The leading Russian journal The Contemporary published Pleshcheyev's first poem the following year, and in 1845 he decided to abandon his university course in order to devote himself to private study in history and political economy, which he considered to be more relevant to the demands of real life in Russia.

Nevertheless, Pleshcheyev had a strong aesthetic vein as well, and after Pauline Viardot's triumphant appearances with the Italian Opera in Saint Petersburg from 1843 to 1846 he wrote a poem dedicated to her, entitled To the Singer (Певице), in which he paid tribute to her interpretations of Norma, Desdemona, and Rosina. In general, Pleshcheyev's verses were not always of the finest quality and he often used hackneyed images, but by the second half of the 1840s he was the most popular poet in Russia because of the civic ideals he proclaimed. To make ends meet, he also wrote short stories and review articles.

In 1845, the Petrashevsky Circle was set up in Saint Petersburg, and Pleshcheyev became one of the most active members of this group which met regularly to talk about the latest ideas of French socialist thinkers. Pleshcheyev was also responsible for introducing his friend Fyodor Dostoyevsky into the Petrashevsky Circle the following year. In the autumn of 1848, on the initiative of Dostoyevsky and Pleshcheyev, a smaller group was established for the discussion of political matters and possibly the dissemination of revolutionary propaganda. Pleshcheyev himself eagerly followed the revolutionary events in France, and in 1846 he had written his most famous poem "Forward! without fear or doubt…" (Вперёд! без страха и сомнения...), evoking the struggle for a better future and saluting those who were prepared to suffer for this noble cause. This poem became known as the hymn of the Petrashevskians.

On 28 April 1849, Pleshcheyev, along with other members of that circle, was arrested in Moscow and accused of having circulated copies of Vissarion Belinsky's Letter to Gogol, a passionate indictment of Russian autocracy. Together with Dostoyevsky and others, he was subjected to the harrowing experience of a mock execution by firing-squad before being sentenced to four years' hard labour. In view of his youth, however, his sentence was commuted to service in the rank and file of a regiment in Orenburg, in the southern Ural region. There he met other political prisoners and exiles, including the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko. During his years in the army (1850–56), Pleshcheyev saw active service in campaigns against the Uzbek Khanate of Kokand, taking part in the capture of an important fortress in 1853. He was promoted to the rank of ensign and allowed to leave the army in December 1856. Still an exile, he worked in the civil service in Orenburg for two years. It was also there that in 1857 he married Yelena Rudneva (1841–1864) whose premature death a few years later would be a bitter blow for him.

In 1859, Pleshcheyev was allowed to live in Moscow again and he soon re-established contacts with the literary journals. Thanks to this he was able to help Dostoyevsky to find a publisher for some of his works written in exile. Pleshcheyev himself contributed poems and essays to The Contemporary before it was closed down by the government in 1866, and he also translated Heinrich Heine's Romantic tragedy William Ratcliffe, which would later serve as the libretto for César Cui's most successful opera. Economic circumstances, however, forced Pleshcheyev to continue working in the civil service.

With his three children, Pleshcheyev moved to Saint Petersburg in 1872, where he obtained a job as secretary for the journal Notes of the Fatherland. In 1878, he gathered all his poems for children into one volume, published as The Snowdrop (Подснежник). Leaving Notes of the Fatherland in 1884, he became head of the literature section of the journal Northern Herald, where he defended younger writers such as Anton Chekhov from attacks by the radical intelligentsia. Pleshcheyev translated not just poetry (mainly Heine, Byron, Goethe, Shevchenko, Tennyson, and various Scottish poets) but also novels by George Sand and Stendhal's Le Rouge et le Noir.

In the 1870s and 80s Pleshcheyev was hailed by the younger generation for his loyalty to the democratic ideals of his youth and his support of student protests. Dostoyevsky, on the other hand, though still grateful for the moral and financial aid he had received from Pleshcheyev, considered him a member of the 'enemy' camp together with other liberals such as Ivan Turgenev.

Only in his last years was Pleshcheyev able to live in greater comfort after inheriting a fortune in 1890. He died in Paris in 1893.

Tchaikovsky and Pleshcheyev

Tchaikovsky first met the poet when he moved to Moscow in January 1866 to teach music theory and began attending gatherings of the Artistic Circle, a club that had been set up by Nikolay Rubinstein and Aleksandr Ostrovsky a few years earlier and which brought together many of the city's leading artists. In her memoirs of Tchaikovsky, Sofya Nyuberg-Kashkina (1872–1964), the daughter of Nikolay Kashkin, recalled an anecdote her father had told her about a soirée in the Artistic Circle at which Tchaikovsky was also present: Rubinstein had introduced Pleshcheyev to a singer whose husband, a colonel, said that he had had the pleasure of meeting the poet before. When Pleshcheyev said that he could not remember where, the colonel explained that he had been the commander of the firing-squad which Pleshcheyev had faced back in 1849. Everyone present was visibly embarrassed "except for the good colonel, who, on the contrary, looked as if he had just said something exquisitely polite to Pleshcheyev" [1].

In a letter to his brothers Anatoly and Modest early in 1866, Tchaikovsky informed them that he had decided to write his own libretto for an opera, adding: "the poet Pleshcheyev is here, and has agreed to assist me with this" [2]. It is not clear what projected opera he was referring to, but at any rate the idea seems to have been abandoned, since it was not until the following year that Tchaikovsky would start working on his first completed stage work, the opera The Voyevoda, with a libretto provided by Ostrovsky. Nevertheless, when quoting the above letter in his biography of the composer, Modest adds an explanatory note: "Aleksey Nikolayevich Pleshcheyev, whose acquaintance Pyotr Ilyich made at the Artistic Circle and who from then on until his death would be a great friend of his" [3].

Certainly, this seems to be borne out by a letter to Anatoly in August 1869 in which Tchaikovsky mentions that together with Mily Balakirev he had visited Pleshcheyev's dacha at Tsaritsyno and spent the night there [4]. It was perhaps this visit which prompted him to set one of Pleshcheyev's poems to music later in November: the song Not a Word, o My Friend (Ни слова, о друг мой) — No. 2 of the Six Romances, Op. 6 (1869) — which is said to be the earliest of Tchaikovsky's tragic songs and belongs to that first cycle of romances which established his reputation in that genre [5].

In a letter to Modest towards the end of 1880, Tchaikovsky asked his brother to visit either Plescheyev or Yakov Polonsky and enquire on behalf of Sergey Taneyev whether they could write the text for a small cantata on the subject of Christ which Taneyev wanted to compose [6]. In the end nothing came of this project, although in 1884 Taneyev did compose a religious cantata John of Damascus (Иоанн Дамаскин) which was based on Aleksey Tolstoy's poem and dedicated to the memory of Nikolay Rubinstein.

In 1881, Pleshcheyev presented Tchaikovsky with a copy of his collection of children's poems The Snowdrop which bore the following inscription: "To Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, as a token of respect and gratitude for his beautiful music set to my poor words. A. Pleshcheyev. 15 February 1881. Petersburg" [7]. The poet evidently had in mind the two songs which Tchaikovsky had so far composed using verses of his: the above-mentioned Not a Word, o My Friend and O, Sing That Song (О, спой же ту песню) — No. 4 of the Six Romances, Op. 16 (1873). Two years after receiving this present, Tchaikovsky would be inspired by Pleshcheyev's heartfelt and vivid poems — some of which are set in the countryside and feature peasant children — to write the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54. Tchaikovsky described his work on this cycle in a letter to Modest from Kamenka in the autumn of 1883: "It is obvious that I cannot live without work here even for a few days, and scarcely had I finished my suite than I set about composing children's songs, carefully writing one each day. But this work is agreeable and easy because I've taken the texts from Pleshcheyev's Snowdrop, which is full of delightful things" [8].

The album was eventually published by Jurgenson in 1884, with no less than fourteen of the songs being settings of verses by Pleshcheyev. In some cases Tchaikovsky modified slightly the original poems or selected only certain strophes, but in his music he tried to be faithful to the clarity of expression and naturalness of Pleshcheyev's verses. (Not all of these were in fact originally written for children [9].)

Replying, in June 1888, to a letter from Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, who had told the composer that he was very pleased with the Six Romances, Op. 63 (which were all settings of the Grand Duke's own poems), Tchaikovsky noted: "I am not at all surprised that Your Highness has written such wonderful verses without being familiar with the theory of versification. Many of our poets have told me the same — for example, Pleshcheyev" [10].

Tchaikovsky's Settings of Works by Pleshcheyev

Completed

- Spring ("I Walk Out Into the Old Garden...") (1853) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Spring Song (Весенняя песня), No. 13 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- In imitation of the Polish (1856), a translation from the Polish of Ludwik Kondratowicz's poem Oracz de skowronka (1851) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Little Bird (Птичка), No. 2 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- My Little Garden (1858) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as My Little Garden (Мой садик), No. 4 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- An untitled poem ("The Grass Grows Green...") in the cycle Country Songs (1858) which comprises translations from unidentified Polish sources — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Spring: The Grass Grows Green (Весна: Травка зеленеет), No. 3 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- A Dreary Scene! (1860) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Autumn (Осень), No. 14 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883)

- Silence (1861), a translation from the German of Moritz Hartmann's poem Schweigen — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Not a Word, o My Friend (Ни слова, о друг мой), No. 2 of the Six Romances, Op. 6 (1869).

- On a Motif of Felicia Hemans (1871), a translation from the English of Felicia Hemans' poem Mother! Oh Sing me to Rest (1830) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as O, Sing That Song (О, спой же ту песню), No. 4 of the Six Romances, Op. 16 (1873).

- Spring (1872) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Spring: The Snow is Already Melting (Весна: Уж тает снег], No. 9 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- Winter Evening (1872) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Winter Evening (Зимний вечер), No. 7 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- In a Storm (1872) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Lullaby in a Storm (Колыбельная песнь в бурю), No. 10 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- The Little Flower: On a Motif of Louis Ratisbonne (1872), a translation from the French of Louis Ratisbonne's poem La Petite fleur — set to music by Tchaikovsky as The Little Flower (Цветок), No. 11 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- The Cuckoo. A Fable by Gellert (1872), a translation from the German of Christian Fürchtegott Gellert's fable Der Kuckuck (1769) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as The Cuckoo (Кукушка), No. 8 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- Excerpt from section No. 2 of the poem From Life (1873) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Winter (Зима), No. 12 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- On the Bank (1874) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as On the Bank (На берегу), No. 6 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- Legend (1877), a translation from the English of Richard Henry Stoddard's poem Roses and Thorns (1857) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Legend (Легенда), No. 5 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- Granny and Grandson (1878) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Granny and Grandson (Бабушка и внучек), No. 1 of the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54 (1883).

- Words for Music (1884) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as The Gentle Stars Shone for Us (Нам звёзды кроткие сияли), No. 12 of the Twelve Romances, Op. 60 (1886).

- O, If Only You Knew (1884), a translation from the French of René-François-Armand Sully Prudhomme's poem Prière (1875) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as O, If Only You Knew (О, если б знали бы), No. 3 of the Twelve Romances, Op. 60 (1886).

- Only You Alone (1884), a translation from the German of Christiane von Breden's poem Nur du allein (1872) — set to music by Tchaikovsky as Only You Alone (Лишь ты один), No. 6 of the Six Romances, Op. 57 (1884).

Unrealised

- The Beggars (1861) — textual notes for a song The Beggars (Нищие), made by Tchaikovsky in 1883 for the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54, but not subsequently used.

- Night Flew Past Over the World, poem No. 6 in the cycle Summer Songs (1862), made by Tchaikovsky in 1883 for the Sixteen Songs for Children, Op. 54, but not subsequently used.

Bibliography

- M. Ya. Polyakov, introductory article in А. Н. Плещеев. Полное собрание стихотворений (Moscow/Leningrad, 1964)

- Романсы и детские песни П. И. Чайковского на стихи А. Н. Плещеева (1980)

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ О Чайковском. Воспоминания свой и чужие (1980), p. 78.

- ↑ Letter 84 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky and Modest Tchaikovsky, 30 January/11 February 1866.

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 1 (1997), p. 216.

- ↑ Letter 143 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 3/15 August 1869.

- ↑ See Романсы и детские песни П. И. Чайковского на стихи А. Н. Плещеева (1980), p. 103.

- ↑ Letter 1651 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 18/30–19/31 December 1880.

- ↑ See Дни и годы П. И. Чайковского. Летопись жизни и творчества (1940), p. 251.

- ↑ Letter 2374 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 20 October/1 November–24 October/5 November 1883.

- ↑ Романсы и детские песни П. И. Чайковского на стихи А. Н. Плещеева (1980), p. 101.

- ↑ Letter 3589 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 11/23 June 1888.