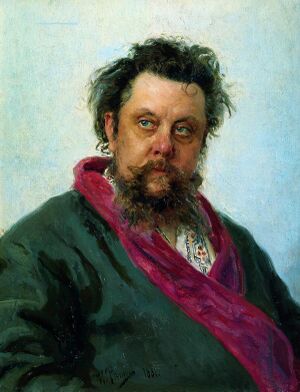

Modest Musorgsky

Russian composer (b. 9/21 March 1839 in Karevo, near Pskov; d. 16/28 March 1881 in Saint Petersburg), born Modest Petrovich Musorgsky (Модест Петрович Мусоргский).

The son of an ancient aristocratic family, Musorgsky spent his childhood years in the countryside, where his mother gave him his first piano lessons. The fairy-tales told by his nanny awakened in him an early love for the Russian peasantry and its creative imagination that would become the main impulse for his own music. In 1849, he was sent to a boarding-school in Saint Petersburg but continued to have piano lessons. Aged 13, he was enrolled in a military academy there (all the instruction was in German, which may perhaps explain his later aversion to everything that reminded him of German academicism). On graduating in 1856, he received a commission with an élite Guards regiment in the Imperial capital.

In 1857, Musorgsky was introduced to Aleksandr Dargomyzhsky, whom he admired as a "great teacher of musical truth" in The Stone Guest and whose extreme naturalism he would adopt to some extent in his own operas. Through Dargomyzhsky he also met Mily Balakirev, Vladimir Stasov, and César Cui. Balakirev agreed to give him lessons in composition, and over the next two years they studied together the scores of many works by Gluck, Mozart, and Beethoven, often transcribing them for piano duet themselves and then playing them through. In 1858, against his friends' advice, Musorgsky resigned his officer's commission in order to devote himself entirely to music.

In the summer of 1859, Musorgsky visited Moscow for the first time and was fascinated by the city's historical aura. To his mentor Balakirev he wrote how this experience had dispelled his earlier cosmopolitanism and made everything Russian dear to him [1]. He sketched out plans for various operas, but none of these were realised. In 1863, Musorgsky realised that he had to seek regular employment because his family's income from their estate (much reduced as a result of the Emancipation Act) was no longer sufficient to support him in Saint Petersburg. He started his career as a civil servant there in December 1863, but continued to help Balakirev to train singers for the latter's Free Music School.

Musorgsky, like most of his friends in the "Mighty Handful", made no secret of his contempt for the Conservatory system introduced by Anton Rubinstein and indeed for any 'German' influences in Russia (after 1870 he would always write Petrograd at the top of his letters instead of the German-sounding Sankt-Peterburg). His most notable early works are all firmly rooted in the world of rural Russia with its joyful and tragic moments: e.g. the song "Darling Savishna" [Светик Савишна] (1866) about a wretched 'holy fool', and an orchestral work St John's Night on the Bare Mountain (Иванова ночь на Лысой горе) (1867), which Musorgsky considered to be his best composition at the time, as it was "an originally Russian work, without a trace of Germanic profundity and routine, a work which poured out from our native fields and was nourished by Russian grain" [2]. In 1868, he started work on an opera The Marriage (Женитьба) based on the comedy by Gogol, his favourite writer. His aim in this opera was to write vocal parts that would be true to the intonation of real speech and yet be highly artistic at the same time. Despite Dargomyzhsky's encouragement, he dropped this project after finishing only one act.

Musorgsky fortunately did complete his next project, and it was to propel him to Russian and eventually world-wide fame: in the autumn of 1868, he started work on his historic opera Boris Godunov, based on Pushkin's 1825 drama but adding a lot of his own text. The "Time of Troubles" into which Russia was plunged in the early seventeenth century inspired the composer, who seized the opportunity which the subject gave him to depict truthfully the Russian people, now submissive (in the Red Square scenes), now mischievous (in the tavern scene), now rebellious and menacing (in the final scene of popular revolt). By December 1869 the piano score was ready, and Musorgsky completed the orchestration of this first version of the opera in the spring of 1870. (This version had no Polish act, although Musorgsky's friends had advised him to write one, pointing to the example of Glinka's A Life for the Tsar.)

On 18/30 May 1870, Tchaikovsky met Musorgsky for the first time, at a soirée in the house of Glinka's sister Lyudmila Shestakova (1816–1906). Tchaikovsky played his recently completed Romeo and Juliet overture, Balakirev his oriental fantasy Islamey, and Musorgsky performed some of his songs and excerpts from Boris Godunov. There was never much likelihood of Tchaikovsky and Musorgsky becoming friends, given the latter's distrust of anything that came from the Conservatory system, but they did meet again a few days later at another musical soirée in the house of Nikolay Purgold (the father of Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov's future wife Nadezhda).

The first version of Boris Godunov was rejected by the Mariinsky Theatre's opera committee in the autumn of 1870 because it lacked a principal female role and had too many choral scenes. With some help from Stasov, who provided him with further vivid historical details, Musorgsky set about revising the opera and adding the Polish act with its culmination in the unusually lyrical duet between the Pretender and Marina. In the autumn of 1871, Rimsky-Korsakov and Musorgsky decided to share a flat, taking turns at the piano to work on their respective operas (Rimsky-Korsakov was then writing The Maid of Pskov). By June 1872, Musorgsky had completed the second version of Boris, but the Mariinsky Theatre still seemed reluctant to give it a chance.

Musorgsky had also been working on a song cycle The Nursery (Детская), which won the praise of Liszt when it was eventually published, and on 28 September/10 October 1872, at a soirée attended by Tchaikovsky, he performed these songs, as well as some scenes from his opera. In a letter he wrote to Stasov, Musorgsky described ironically how Tchaikovsky had dozed off while he sang and acted out the two tramps Varlaam and Misail in the Inn Scene, which had probably made the "Conservatory professor" dream of "Muscovite sour bread", and how Tchaikovsky had only livened up during the Tsarevich Fyodor's Parrot Song. At the end, Tchaikovsky had made some compliments about Musorgsky's raw power but advised him to try writing a symphony instead. They had met again by chance a few days later at the music-shop of Vasily Bessel, and Tchaikovsky apparently exhorted him again to "give us musical beauty — just musical beauty!" [3].

On 5/17 February 1873, as a benefit performance for the baritone Gennady Kondratyev, three scenes from Boris Godunov were staged at the Mariinsky Theatre, with Eduard Nápravník conducting. The singers and the audience were greatly impressed, and the dramatic soprano Yuliya Platonova (1841–1892), who had sung Marina in the two scenes from the Polish act, insisted that the whole opera be staged. The director of the Imperial Theatres, Stepan Gedeonov, intervened and overruled the opera-committee's earlier decision. Finally, on 27 January/8 February 1874, Musorgsky's opera had its complete premiere at the Mariinsky Theatre. It was a tremendous success with the public, but provoked some hostile reviews — in particular, one by César Cui, which came as a bolt from the blue to Musorgsky (who would afterwards consider Cui a traitor to the cause of the "Mighty Handful"), and, more predictably, one from Tchaikovsky's friend Herman Laroche, who called Boris Godunov "a musical asafoetida".

Tchaikovsky's own negative reaction may have been aggravated by a bit of jealousy against Musorgsky because his own opera The Oprichnik, which, unlike Boris, had been accepted by the opera-committee from the start, did not awaken nearly as much interest as the latter and was not staged at the Mariinsky Theatre until 12/24 April 1874 [4]. Moreover, Tchaikovsky could not really warm to an opera which ended with a scene showing some peasants about to take justice into their hands and execute a captured boyar (this scene would be excised in the new production of Boris in 1876, much to the indignation of Stasov). After all, Tchaikovsky would later turn down the suggestion of writing an opera The Captain's Daughter, based on Pushkin's novel, because "the Pugachev rebellion frightens me" (Letter 2690 to Pavel Pereletsky, 21 April/3 May 1885). Although Tchaikovsky did not attend the premiere of Musorgsky's opera or any later performances that year, he did study the score and wrote about this to his brother Modest on 29 October/10 November 1874: "I have studied thoroughly Boris Godunov and The Demon [by Anton Rubinstein]. Musorgsky's music I send with all my heart to the devil — it is the most vulgar and base parody on music" [5].

After Musorgsky had finished orchestrating the first version of Boris in 1870, Stasov had given him the idea of writing a new opera, Khovanshchina (The Khovansky Affair) on the political turmoil surrounding the accession of Peter the Great in 1682. Musorgsky soon started making sketches for this opera — or "popular drama" (народная драма) as he called it — and letters from those years show how passionately he felt about this task. His deep sympathy for the Russian people and hatred of all self-appointed benefactors, who wanted to reform it by force if need be, would inspire his moving portrayal of the Old Believers and their leader Dosifey. Moreover, encouraged by his reading of Charles Darwin, Musorgsky was convinced that the laws of art were ever changing, and that classical notions of beauty were no longer relevant. His mission as he saw it was to advance "towards new shores" [к новым берегам!] in art and conquer new territory. In Khovanshchina he wanted to "turn up the black earth" of Russia's past and present and "talk truthfully to people" [6].

Although he worked enthusiastically on Khovanshchina at first (by July 1873 he had completed the wonderfully lyrical overture and the sketches for several scenes) and the success of Boris Godunov in 1873–1874 clearly boosted his morale, feelings of isolation would drive him increasingly to drink. One by one he was left without his closest friends: the artist Viktor Hartmann, whose death in 1874 prompted him to write the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition; Rimsky-Korsakov, who, in Musorgsky's view, had betrayed the "Mighty Handful" by drifting into academicism at the Conservatory; and also the poet Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov (with whom Musorgsky collaborated on two song cycles), when he left Saint Petersburg. He also became estranged from Stasov, who was disgusted by Musorgsky's alcoholism and gradually lost any hope of seeing Khovanshchina completed, especially as the composer had interrupted work on the latter in July 1874 to write a comic opera Sorochintsy Fair, again based on Gogol. This was yet another project which would remain unfinished.

Tchaikovsky may or may not have heard rumours about Musorgsky's moral decline in the second half of the 1870s, but his antipathy towards him was based mainly on what he perceived to be the uncouthness of Boris Godunov's music. Nevertheless, Tchaikovsky was able to appreciate something of the latter's power and originality. In his reply of 24 December 1877/5 January 1878 to Nadezhda von Meck's enquiry about his views on the composers of the "Mighty Handful", he said the following about the author of Boris: "You are quite right to call Musorgsky a hopeless case. In terms of talent he is, perhaps, higher than all of the preceding ones [Rimsky-Korsakov, Cui, and Borodin], but his is a narrow nature, devoid of any need for self-perfection, with a blind faith in the absurd theories of his circle and in his own genius. Besides, it is a base nature which relishes coarseness, uncouthness, and roughness. He is the complete opposite to his friend Cui, who is always shallow but at least manages to be that in a seemly and elegant way. Musorgsky, in contrast, flaunts his illiteracy, takes pride in his ignorance, and turns out [his works] anyhow, blindly believing in the infallibility of his genius. And yet he does sometimes have flashes of real talent, and, moreover, not without originality... For all his ugliness, Musorgsky does speak to us in a new language. It may not be beautiful, but it is fresh" [7].

Musorgsky's increasingly irregular record of attendance at work finally led to him being dismissed from his post in January 1880. Stasov and some friends clubbed together to provide him with a monthly pension so that he could complete Khovanshchina and Sorochintsy Fair. By August he had finished the sketches for his second historic opera, except for the Old Believers' auto-immolation scene at the end, but only two numbers had been orchestrated. After that, however, his bouts of alcoholism intensified, and, although his friends managed to intern him in a good hospital in February 1881 and for a few weeks he seemed to be making a good recovery, he drank himself to death on 16/28 March 1881. He was buried in the Tikhvin Cemetery at the Aleksandr Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg.

Rimsky-Korsakov took on the task of orchestrating his late friend's opera (and completing the final act), and Khovanshchina was published by Bessel in 1883. Tchaikovsky decided to study the score the following year, and he shared his impressions with Nadezhda von Meck in a letter from Pleshcheyevo dated 8/20–10/22 September 1884: "In Khovanshchina I found precisely what I had been expecting: a pretension to realism, though the latter is understood and applied in a peculiar manner, lamentable technique, poverty of invention, every now and then talented episodes, but always in a sea of harmonic nonsense and that mannerism so characteristic of the circle of musicians to which Musorgsky belonged" [8]. Nevertheless, in the letter he wrote to the German conductor Julius Laube in June 1888, advising him to select works by other Russian composers to play in Pavlovsk that summer, Tchaikovsky did mention Musorgsky specifically [9]. The musicologist Richard Taruskin has also suggested that some elements of Boris Godunov may well have influenced Tchaikovsky in certain scenes of his opera Mazepa (1883).

Khovanshchina in Rimsky-Korsakov's version was first staged by an amateur company in Saint Petersburg on 9/21 February 1886, and in Moscow the following year by Savva Mamontov's private opera company (with a young Feodor Chaliapin as Dosifey).

External Links

Bibliography

- М. П. Мусоргский. К 45-летию со дня смерти (1926)

- Tchaikovsky on The Five (1940)

- Tchaikovsky on The Five (1969)

- Pekelis, M. S. (ed.). Модест Петрович Мусоргский: Литературное наследие. Том 1: Письма. Биографические материалы и документы (Moscow, 1971)

- Nationalism, modernism and personal rivalry in nineteenth-century Russian music (1981)

- Abyzova, Ye. Modest Petrovich Musorgsky (1986)

- Что же ставить сегодня? Личные наблюдения композитора над парадоксами отечественной оперы (1991)

- Tschaikowsky. Ein Anhänger der Religion bedingungsloser Schönheit (1994)

- Čajkovskij und das Mächtige Häuflein (1995)

- Truth vs. beauty. Comparative text settings by Musorgsky and Tchaikovsky (1999)

- Мусоргский и Чайковский. Опыт сравнительной характеристики (2001)

Notes and References

- ↑ Letter from Modest Musorgsky to Mily Balakirev, 23 June/5 July 1859.

- ↑ Letter from Modest Musorgsky to Vladimir Nikolsky, 12/24 July 1867.

- ↑ Musorgsky's letter is quoted (in German translation) by Thomas Kohlhase in An Tschaikowsky scheiden sich die Geister. Textzeugnisse der Čajkovskij-Rezeption, 1866-2004 (2006), p. 51.

- ↑ See Letter 322 to Vasily Bessel, 18/30 October 1873.

- ↑ Letter 368 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 29 October/10 November 1874.

- ↑ From Musorgsky's letters to Vladimir Stasov, 16/28 June–22 June/4 July 1872) and Lyudmila Shestakova, 29 February/12 March 1876.

- ↑ Letter 705 to Nadezhda von Meck, 24 December 1877/5 January 1878.

- ↑ Letter 2545 to Nadezhda von Meck, 8/20–10/22 September 1884.

- ↑ See Letter 3587a to Julius Laube, 10/22 June 1888.