Letter 3578

| Date | 30 May/11 June 1888 |

|---|---|

| Addressed to | Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich |

| Where written | Frolovskoye |

| Language | Russian |

| Autograph Location | Saint Petersburg (Russia): Institute of Russian Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Pushkin House), Manuscript Department (ф. 137, No. 78/9) |

| Publication | Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1902), p. 244–246 П. И. Чайковский. Полное собрание сочинений, том XIV (1974), p. 440–442 К.Р. Избранная переписка (1999), p. 45-47 |

Text and Translation

| Russian text (original) |

English translation By Luis Sundkvist |

Г[ород] Клин, с[ело] Фроловское 30-го мая 1888 г[ода] Ваше Императорское Высочество!

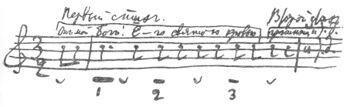

Я несколько замедлил ответом на письмо Ваше вследствие того, что оно пришло сюда, когда я находился в Москве по делам, а когда оно нагнало меня в Москве, то я только что выехал в с. Фроловское. Спешу извиниться в невольной вине перед Вами. Очень радуюсь, что Ваше Высочество не рассердились на меня за мои замечания, и искренно благодарю за сделанные по поводу их разъяснения. Но Вы слишком снисходительны, называя меня знатоком. Нет! я именно дилетант в деле версификации, давно собираюсь основательно познакомиться с ним и до сих пор ещё не удосужился спросить у авторитетных людей, каким образом это сделать, т. е. имеется ли какой-нибудь классический труд по этой части? Многие вопросы меня интересуют, и никогда никто не мог мне вполне ясно и определённо ответить на них. Напр[имер]: читая «Одиссею» Жуковского, или его «Ундину», или «Илиаду» Гнедича, я страдаю от несносного однообразия русского гекзаметра, сравнительно с коим латинский (греческий язык мне незнаком), напротив, полон разнообразия, силы и красоты. Знаю даже, что недостаток этот происходит от неимения у нас спондея, но почему у нас нет спондея, — этого я никак понять не могу и нахожу, что он у нас есть. Меня также чрезвычайно занимает вопрос, почему сравнительно с русским стихом немецкий не так упорно придерживается строгого последования стопы за стопой в том же ритме? Когда читаешь Гёте, то удивляешься смелости его относительно стоп, цезур и т. д., доходящей до того, что малопривычному слуху иной стих представляется даже почти не стихом? А между тем слух лишь удивлён при этом, а не оскорблён. Случись у русского стихотворца что-либо подобное (как в данном случае в слове преторианец), то чувствуется нечто неприятное. Почему это? Есть ли это результат особенных свойств языка или просто традиции, допускающие у немцев всякого рода вольности, а у нас таковых не допускающие? Я не знаю, Ваше Высочество, так ли я выражаюсь, но я хочу констатировать тот факт, что от русского стихотворца требуется бесконечно большей правильности, отделанности, музыкальности, а главное вылощенности, чем от немецкого. Хотелось бы когда-нибудь разъяснить себе, почему это так. А пока разъяснения не будет, я буду продолжать свою дилетантскую требовательность и придирчивость к ударениям, цезурам и рифмам в русском стихотворстве. По поводу пятистопного хорея я хотел сказать Вашему Высочеству, что для меня этот размер представляется ритмом в 3/2, причём начинается стих за тактом. В такте этом есть один удар, а именно первый, который есть безусловно сильное время (так называемый арзис), и два относительных, происшедших от подразделения двух слабых времён (тезисов) на два. Итак, пятистопный хорей музыкально может быть воспроизведён так: Мне кажется, мне чувствуется, что на первом из трёх сильных времён ударение совершенно необходимо, так что (быть может, в качестве музыканта) мне неловко, если я на этом месте встречаю слог «то» из слова преторианец. В конце концов, конечно, я не прав, ибо такой изумительный мастер стиха, как Фет, оправдывает скрадывание цезуры в таком месте, где по музыкальным законам его быть не может. Из этого, вероятно, вытекает то заключение, что я отношусь к стихам как музыкант и вижу нарушение ритмического закона там, где его с точки зрения версификации вовсе нет или если есть, то оно извинительно. Капитанскую дочку не пишу и вряд ли когда-нибудь напишу. По зрелом обдумании я пришёл к заключению, что этот сюжет неоперный. Он слишком дробен, требует слишком многих не подлежащих музыкальному воспроизведению разговоров, разъяснений и действий. Кроме того, героиня Марья Ивановна недостаточно интересна и характерна, ибо она безупречно добрая и честная девушка — и больше ничего, — а этого для музыки недостаточно. При распределении сюжета на действия и картины оказалось, что таковых потребуется ужасно много, как бы ни заботиться о краткости. Но самое важное препятствие (для меня, по крайней мере, ибо весьма возможно, что другому оно бы нисколько не мешало) — это Пугачёв, пугачёвщина, Берда и все эти Хлопуши, Чики и т. п. Чувствую себя бессильным их художественно воспроизвести музыкальными красками. Быть может, задача эта и выполнима — но она не по мне. Наконец, несмотря на самые благоприятные условия, я не думаю, чтобы оказалось возможным появление на сцене Пугачёва. Ведь без него обойтись нельзя, а изображать его приходится таким, каким он у Пушкина, т. е., в сущности, удивительно симпатичным злодеем. Думаю, что как бы цензура ни оказалась благосклонной, она затруднится пропустить такое сценическое представление, из коего зритель уходит совершенно очарованный Пугачёвым. В повести это возможно — в драме и опере вряд ли, по крайней мере у нас. В настоящее время я намерен написать симфонию, а затем, если найдётся способный согреть и воодушевить меня сюжет, то, может быть, и оперу напишу. Последнее письмо Вашего Высочества особенно глубоко тронуло меня и усугубило, если возможно, чувство живейшей и почтительнейшей преданности к особе Вашей. Имею честь быть покорнейший слуга Ваш. П. Чайковский |

Your Imperial Highness!

I have been somewhat tardy in replying to your letter because it arrived here when I was away in Moscow on business [1], and when it caught up with me in Moscow I had in fact just left for Frolovskoye. I hasten to apologise for having unwittingly made myself blameworthy in your eyes. I am very glad that Your Highness is not angry with me for my comments, and I am sincerely grateful for the clarifications which you made with regard to them [2]. However, you are far too generous when you refer to me as a connoisseur. No! For I am very much a dilettante in the field of versification. I have long since been intending to familiarise myself with it thoroughly, but so far I have not found the time to ask competent people how I should go about this — that is, whether there is perhaps some classical handbook in this field? There are many questions that interest me, and no one has ever been able to give me entirely clear and definite answers to them. For example: when reading Zhukovsky's Odyssey or his Undina [3], or Gnedich's Iliad [4], I suffer from the unbearable monotony of the Russian hexameter, compared to which the Latin hexameter (I have no knowledge of Greek) is, in contrast, full of variety, strength, and beauty. I am even aware that this shortcoming is due to our lacking the spondee, but why we don't have spondees, that is something I just cannot understand, and indeed I would say that we do have them. I am also extremely interested by the question as to why in comparison to Russian verse, German verse does not adhere so doggedly to a strict succession of feet in the same rhythm. When one reads Goethe, one is amazed by his audacity with regard to feet, caesuras etc. — an audacity which reaches a point where to an unaccustomed ear it might almost seem as if this or that verse is not actually a verse at all. And yet, one's ear is merely amazed by this, not offended. When something similar happens in the work of a Russian poet (as in the given case in the word Praetorian [5], the effect is an unpleasant one. Why is this so? Is this the result of specific properties of our respective languages, or is it simply a case of traditions which allow all kinds of liberties in German verse, whilst denying them to us? I am not sure, Your Highness, whether I am expressing myself correctly, but I want to establish the fact that infinitely more regularity, evenness, musicality, and most importantly, polish are expected of Russian poets than is the case with German ones. I should like some day to clarify for my own benefit why this is so. However, until such clarification is forthcoming I shall continue my dilettantish exactingness and captiousness regarding stresses, caesuras and rhythms in Russian poetry. With regard to trochaic pentameter, I should like to tell Your Highness that to me this metre appears to be in 3/2 time, with the verse beginning on the upbeat the measure begins. In this measure there is one beat, namely the first, which is an absolutely strong beat (a so-called arsis), and two relative ones which arise from the subdivision of two weak beats (theses) into two. Thus, the trochaic pentameter can be reproduced musically as follows: It seems to me, or rather, I feel that a stress is utterly essential on the first of these three strong beats, and this means that (perhaps because I am a musician) it feels awkward for me if in that position I encounter the syllable "to" from the word "Praetorian". Of course, when all is said and done I am wrong, because such an astonishing master of verse as Fet defends the suppression of the caesura in a position where according to the laws of music that cannot happen [6]. From this one may probably draw the conclusion that my attitude to verses is that of a musician, and that I see a violation of the law of rhythm in a case where, from the point of view of versification, there is no such violation at all, or if there is, then it is excusable. I am not writing The Captain's Daughter and it is hardly likely that I shall ever do so [7]. Upon mature deliberation I have come to the conclusion that this is not an operatic subject. It is much too fragmentary, it requires far too many conversations, explanations, and actions which are not susceptible of musical illustration. Moreover, the heroine Marya Ivanovna is insufficiently interesting and original, because she is just an irreproachably good and honest girl, and nothing more — and that is not enough for music. When dividing the scenario into acts and scenes it turned out that there would have to be an awfully great deal of these, no matter how much one strives for brevity. However, the most important obstacle (at least for me, since it is quite possible that it wouldn't bother someone else at all) is Pugachev, the Pugachev rebellion, Berda, and all these Khlopushkas, Chikas, and so on [8]. I feel incapable of portraying them artistically using musical colours. Perhaps it is a feasible task, but I'm just not up to it [9]. Finally, in spite of the most favourable conditions, I don't think it would be possible to have Pugachev appear onstage. I mean, dispensing with him is impossible, and he would have to be portrayed as he comes across in Pushkin's novel, that is, essentially as a surprisingly likeable villain. I think that however well-disposed the censorship may be, it will find difficulty in passing a stage production from which the spectator will come away utterly enchanted by Pugachev. In a novel that is possible, but in a drama or opera hardly so — at least not in our country. At present I intend to write a symphony [10] and after that, if a subject turns up which is capable of rousing and inspiring me, then perhaps I may indeed also write an opera. Your Highness's last letter moved me particularly profoundly and has intensified even further, if that were possible, my sense of the keenest and most respectful devotion for you. I have the honour of remaining your most humble servant. P. Tchaikovsky |

Notes and References

- ↑ In late May/early June 1888 Tchaikovsky was in Moscow to attend to various matters connected with the Russian Musical Society and the Conservatory.

- ↑ Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich had sent Tchaikovsky a copy of his poem St. Sebastian, which dealt with the Christian martyr, asking him for his opinion on it, and Tchaikovsky, whilst praising the poem on the whole, had singled out the opening of a verse in which he felt that there should be a metrically strong syllable in the second foot, whereas the word used there ("Praetorian") had an unstressed syllable in that position (see letter 3574 of 8/20 May 1888). Konstantin had replied on 24 May/5 June 1888, thanking Tchaikovsky for his comments. The Grand Duke's letter has been published in К.Р. Избранная переписка (1999), p. 44-45.

- ↑ The Russian poet Vasily Zhukovsky (1783-1852) worked on his translation of Homer's Odyssey from 1842 to 1849. The translation was dedicated to Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich, the father of Tchaikovsky's august patron and correspondent. Undina (1831-1836) was Zhukovsky's adaptation, in hexameters, of the German romanticist Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's short novel Undine (1811). Tchaikovsky's second opera Undina (1869) was based on this subject. The composer subsequently destroyed the score of his opera, but in 1886-87 he considered returning to the same subject for a ballet Undina — note based partly on the note by L. K. Khitrovo in К.Р. Избранная переписка (1999), p. 47.

- ↑ The Russian poet Nikolay Ivanovich Gnedich (1784-1833) translated Homer's Iliad in 1829.

- ↑ This is the word in the Grand Duke's poem St. Sebastian which Tchaikovsky commented on in his previous letter.

- ↑ In his letter of 24 May/5 June 1888 the Grand Duke said that he agreed entirely with Tchaikovsky's comment about the awkwardness of the word "Praetorian" in a particular position in one verse in his poem St. Sebastian (see Note 2 above), but explained that it had in fact been the veteran poet Afanasy Fet, to whom he had sent his poem earlier, who had corrected that verse for him and put the word "Praetorian" in that position.

- ↑ In his letter of 24 May/5 June 1888 the Grand Duke wrote that he had seen some press reports which suggested that Tchaikovsky was composing an opera based on Pushkin's historical novel The Captain's Daughter (1836), which is set during the time of the Pugachev Rebellion of 1773. This novel had been suggested to Tchaikovsky as a possible opera subject already in 1885, but he had never really warmed to it and nothing came of the projected opera The Captain's Daughter.

- ↑ The Don Cossack Yemelyan Pugachev (1742-1775), leader of the rebellion named after him which swept through east and south-east Russia in 1773, established one of his camps in the settlement of Berda. Khlopushka and Chika were the nicknames of two of his lieutenants. The rebel forces were mainly drawn from the peasantry who were keen to take revenge on the gentry after centuries of exploitation.

- ↑ It is very likely that Tchaikovsky is thinking here of his late 'rival' Musorgsky, who in his opera Boris Godunov had so vividly depicted various figures from the Russian populace, particularly the ruffians Varlaam and Misail who are eventually shown joining the ranks of the Pretender Dmitry. Tchaikovsky had been rather envious of the triumphant success of that opera in 1874, and he criticised the latter for what he considered to be the "uncouthness" of its musical idiom, although he does seem to have recognised Musorgsky's originality.

- ↑ The Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64.