Bernhard Cossmann and Franz Liszt: Difference between pages

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

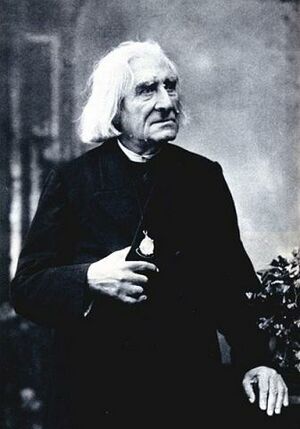

{{picture|file= | {{picture|file=Franz Liszt.jpg|caption='''Franz Liszt''' (1811-1886)}} | ||

Hungarian composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher (b. 22 October 1811 {{NS}} in Raiding [now Doborján], near Sopron; d. 31 July 1886 {{NS}} in [[Bayreuth]]), born '''''Liszt Ferenc'''''. | |||

==Tchaikovsky and Liszt== | |||

Although Liszt — like [[Berlioz]], [[Meyerbeer]], and to some extent [[Wagner]] — was one of the 'forbidden' modern composers whose works Tchaikovsky and [[Herman Laroche]] would play through as students at the [[Saint Petersburg]] Conservatory, in defiance of the classical precepts of their teachers, it seems that Tchaikovsky never really warmed to Liszt's music. [[Laroche]] himself would emphasize, when recalling his late friend's musical sympathies, how "Pyotr Ilyich came slowly, waveringly, and distrustfully to Liszt [...] Of the symphonic poems only ''Orfeo'' roused any real enthusiasm during his time at the Conservatory. It was only much later that he came to love the ''Faust-Symphonie'', and for the sake of impartiality it is worth adding that Liszt's symphonic poems, which enthralled a whole generation of Russian musicians, exerted but an ephemeral and external influence on the style of his own compositions" <ref name="note1"/>. One reason for this distrust towards Liszt may have been his vigorous campaigning for the 'new German school of music', as all such proselytizing in the name of new and radical principles repelled Tchaikovsky's nature (this also partly explains his ambivalence towards [[Wagner]]). More importantly, however, Liszt's music was deficient in substance as far as Tchaikovsky was concerned. He made this clear in a letter to [[Nadezhda von Meck]] from [[Rome]], shortly after attending a concert in Liszt's honour in December 1881: | |||

{{quote|The day before yesterday I was at a gala concert in honour of the 70-year-old Liszt. The programme was drawn up exclusively from his works. [...] Liszt himself was present at this concert. It was impossible not to be moved by the sight of this great old man, who was touched and shaken by the ovations which the enthusiastic Italians gave him. However, Liszt's works as such leave me cold: poetic intentions predominate in them over real creative force, colouring over draughtsmanship — in short, despite all their effective packaging, they are marred by an emptiness of inner content. He is the complete opposite of [[Schumann]], whose awesome, mighty creative force was mismatched with a greyish, colourless exposition of the musical ideas <ref name="note2"/>.}} | |||

In his obituary of Tchaikovsky, [[Nikolay Kashkin]] wrote in similar terms of his late friend's attitude to Liszt: "Pyotr Ilyich could not stand bombast in music, and that is why he did not rate Liszt particularly highly" <ref name="note3"/>. | |||

Nevertheless, when Tchaikovsky was just starting out as a composer, it was very difficult not to fall under the sway of the new ideas proclaimed by Liszt and his followers — namely, that programme music, with its greater freedom of expression, was the way forward. Thus, in some of his earliest orchestral works Tchaikovsky paid tribute to this craze for music which illustrated a specific subject. This was the case with the symphonic fantasia ''[[Fatum]]'' (1868), which [[Laroche]] sharply criticized in a review for its proximity to the Lisztian model of symphonic poems, with their "sombre and tragic" subjects, as well as their "jarring dissonances and bizarre orchestral effects" that, according to [[Laroche]], were not at all congenial to the nature of Tchaikovsky's talent as it had expressed itself in his [[First Symphony]] (1866) <ref name="note4"/>. Despite this criticism (which eventually prompted the composer to destroy the score of ''[[Fatum]]''), Tchaikovsky never dissociated himself entirely from the programme music championed by Liszt and [[Berlioz]]. Indeed, just a year later, when he was still under the influence of [[Mily Balakirev]] (who, like the rest of the "Mighty Handful", admired Liszt for his boldness and also for his early support of Russian music in the 1840s), Tchaikovsky would write yet another piece of programme music: ''[[Romeo and Juliet]]'' (1869). Although this overture-fantasia would eventually become one of Tchaikovsky's most beloved works, both in Russia and abroad, it is interesting that the fiercely conservative Austrian critic Eduard Hanslick attacked the overture after a performance in 1876, calling its author "a disciple of Liszt" and ridiculing the "melodramatic noise and smoke effects" of this "tone-painting", whose subject Tchaikovsky, in Hanslick's view, had borrowed from [[Shakespeare]] following Liszt's example <ref name="note5"/>. | |||

Even if Tchaikovsky would have protested at being bracketed in this way with the 'new' German or even the new Russian school of music, it is significant that he always kept returning to the 'Lisztian' genre of programme music throughout his life (e.g. ''[[Francesca da Rimini]]'', '' [[Manfred]]'', ''[[Hamlet (overture-fantasia)|Hamlet]]''). Likewise, his attitude towards Liszt's music was not as negative as the above letter to [[Nadezhda von Meck]] might suggest. In his feuilleton articles during the 1870s Tchaikovsky praised a number of works by the Hungarian composer, especially his religious oratorios, which expressed the "profoundly moving poetry of Christian love", and in the case of the symphonic piece '' Totentanz'' [''Dance of Death''] he actually defended Liszt, a "profound and sensitive artist", as he called him, against those who wished to see nothing but realistic depictions in his music. (References to these articles are listed below.) With regard to Liszt's two piano concertos, however, he seems always to have found them "brilliant but empty". [[Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov]] later recalled how he had started humming the theme from Liszt's First Piano Concerto during a walk with Tchaikovsky around [[Maydanovo]] in March 1887, and how the latter had then berated him: "Please don't remind me of that play-actor. I can't stand his insincerity and affectation!" <ref name="note6"/>. | |||

Tchaikovsky first met Liszt at the inaugural [[Bayreuth]] Festival in the summer of 1876, and he was delighted to see before him that "wonderful, characteristic grey head", which had always fascinated him on the photographs he had seen of the veteran composer (see Chapter IV of [[TH 314]]) <ref name="note7"/>. Liszt for his part seems to have appreciated the younger man's music, as we may see from a letter which the cellist [[Wilhelm Fitzenhagen]] sent to Tchaikovsky from [[Wiesbaden]] in 1879, telling him about a performance there of the ''[[Variations on a Rococo Theme]]'': "It gives me great pleasure to be able to report to you that I performed your ''[[Variations on a Rococo Theme|Variations]]'' to a tremendous furore! [...] Liszt told me: 'You played magnificently. This is truly music!', and it is a tremendous compliment that such a thing could be said by Liszt!" <ref name="note8"/> Even so, Tchaikovsky himself believed that Liszt was not really an admirer of his music: "I think that he genuinely preferred Messrs [[Cui]] and others who went cap in hand to him in Weimar, and whose music he also liked. As far as I know, he didn't feel any particular sympathy for my music" <ref name="note9"/>. | |||

Nevertheless, in 1880, Liszt made a brilliant paraphrase for piano of the Act III Polonaise from ''[[Yevgeny Onegin]]'', which [[Nikolay Rubinstein]] was the first to perform in [[Moscow]]. Liszt was thereby in effect repaying a compliment which Tchaikovsky had made in 1874, when he arranged for orchestra Liszt's ballad ''[[Der König von Thule (Liszt)|Der König von Thule]]'' (a setting of Gretchen's song in [[Goethe]]'s ''Faust''). So despite his reservations about Liszt as a composer, it must have been very gratifying for Tchaikovsky, during his first concert tour to [[Leipzig]] in January 1888, to discover that the young members of the city's Liszt Society (''Liszt-Verein'') were all enthusiastic admirers not only of his own music, but also that of his colleagues back in Russia (see Chapter VIII in [[TH 316]]) — just as Liszt himself had been one of the earliest champions of Russian music in Western Europe. | |||

==Tchaikovsky's Arrangements of Works by Liszt== | |||

* ''[[Der König von Thule (Liszt)|Der König von Thule]]'', TH 186 (1874) — arrangement for orchestra of Liszt's ballad for voice with piano, S.278 (1843, rev. 1856). | |||

* ''Preghiera'' — third movement of [[Suite No. 4]] ("Mozartiana"), Op. 61 (1887) — orchestral arrangement of the second section from Liszt's ''Evocation à la Chapelle Sixtine'', S.658 (1862–65), which was itself a piano transcription of [[Mozart]]'s chorus ''Ave verum corpus'', KV 618. | |||

==General Reflections on Liszt== | |||

Bold references indicate particularly detailed or interesting references. | |||

===In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles=== | |||

* '''[[TH 268]]''' — Tchaikovsky discusses Liszt's sacred music, praising his "genuinely religious disposition" and comparing it to the masses written by [[Beethoven]], which, like all of the German's symphonic music, were "lyric effusions of sentiment" merely using the words of the liturgy as a pretext. | |||

* '''[[TH 269]]''' — praises Liszt for the "richness of his orchestral and harmonic technique" and calls him "a profound and sensitive artist". | |||

* [[TH 277]] — argues that Liszt is one of those composers like [[Mendelssohn]] or [[Balakirev]] who lacked inventive power but were nevertheless able to "extract everything contained in the embryo of a musical idea" by means of brilliant orchestral effects. | |||

* '''[[TH 305]]''' — compares the "morbid pursuit of staggering effects" in Liszt's "bombastic" ''Dante Symphony'' with the modest simplicity and beauty of the overture to [[Mozart]]'s ''Die Zauberflöte.'' | |||

===In Tchaikovsky's Letters=== | |||

* [[Letter 1341]] to [[Nadezhda von Meck]], 18/30 November 1879, in which Tchaikovsky writes very critically of a joint work by [[Borodin]], [[Cui]], [[Lyadov]], and [[Rimsky-Korsakov]], the ''Paraphrases sur un thème obligé'', noting that the fact that Liszt had praised it meant nothing: | |||

{{quote|As far as Liszt is concerned, this old Jesuit responds with exaggeratedly enthusiastic compliments to any work that is sent to him for his venerable perusal. He is essentially a good man and one of very few outstanding artists in whose heart there was never any petty envy or inclination to obstruct his fellow-artists' success ([[Wagner]] and, to some extent, [[Anton Rubinstein]] are obliged to him for their success; to [[Berlioz]], too, he rendered many services), but on the other hand he is too much of a Jesuit to be capable of being truthful and sincere.}} | |||

* [[Letter 1949]] to [[Nadezhda von Meck]], 30 January/11 February 1882, in which Tchaikovsky describes a chamber music concert in [[Rome]] at which a new string quartet by [[Giovanni Sgambati]] was played. Tchaikovsky had found this work awful: | |||

{{quote|And yet Liszt, who was sitting there in a prominent place, surrounded by a whole bouquet of lady admirers, pretended in the most cunning fashion to go into raptures over it. How I dislike this trait in Liszt! He never says the truth and always praises everything unconditionally. People write to me in their letters that it is wrong of me not to call on Liszt given that we are living in the same city. However, on no account will I ever go and visit him, because to his cloying compliments it is necessary to reply in like, that is with flattery, and that is so loathsome to me!}} | |||

==Views on Specific Works by Liszt== | |||

Bold references indicate particularly detailed or interesting references. | |||

===In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles=== | |||

* ''Années de pèlerinage'', Suite No. 1, S.160 (1848–55) — [[TH 278]] | |||

* ''Christus'', oratorio, S.3 (1866–72) — '''[[TH 268]]''' | |||

* ''Dante'' symphony, S.109 (1855–56) — [[TH 305]] | |||

* ''The Legend of Saint Elisabeth'', oratorio, S.2 (1857–62) — '''[[TH 268]]''' | |||

* Piano Concerto No. 2 in A major, S.125 (1839, rev. 1861) — [[TH 287]] | |||

* ''Prometheus'', symphonic poem, S.99 (1850, rev. 1855) — [[TH 273]] | |||

* ''Totentanz'' (Paraphrase on "Dies irae"), for piano with orchestra, S.126 (1847, rev. ca.1862) — '''[[TH 269]]''' | |||

==Bibliography== | |||

* {{bib|1958/23}} (1958) | |||

* {{bib|1982/21}} (1982) | |||

* {{bib|1982/22}} (1982) | |||

* {{bib|1982/23}} (1982) | |||

* {{bib|1983/24}} (1983) | |||

* {{bib|1983/32}} (1983) | |||

* {{bib|2006/32}} (2006) | |||

==Correspondence with Tchaikovsky== | ==Correspondence with Tchaikovsky== | ||

Not long before his death in 1886, Liszt also sent Tchaikovsky a signed photograph with a brief accompanying letter, which is now preserved in the {{RUS-KLč}} at [[Klin]] | |||

(a{{sup|4}}, No. 2141) <ref name="note10"/>. | |||

==External Links== | ==External Links== | ||

* [[wikipedia: | * [[wikipedia:Franz_Liszt|Wikipedia]] | ||

* {{viaf| | * {{IMSLP|Liszt,_Franz}} | ||

* {{viaf|64199483}} | |||

==Notes and References== | ==Notes and References== | ||

<references> | <references> | ||

<ref name="note1"> | <ref name="note1">{{bib|1979/64}} (1979), p. 65; English translation in {{bib|1993/33|Tchaikovsky Remembered}} (1993), p. 24.</ref> | ||

<ref name="note2"> | <ref name="note2">[[Letter 1902]] to [[Nadezhda von Meck]], 26 November/8 December–27 November/9 December 1881.</ref> | ||

<ref name="note3">{{bib|1980/70}} (1980), p. 361.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note4">[[Laroche]]'s review is quoted in {{bib|2006/18|Textzeugnisse der Čajkovskij-Rezeption 1866–2004}} (2006), p. 48–51.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note5">Eduard Hanslick's review is quoted in {{bib|2006/18|Textzeugnisse der Čajkovskij-Rezeption 1866–2004}} (2006), p. 57–58. At the end of this review he alluded to the example of Liszt's 1858 symphonic poem ''Hamlet''. The formidable Austrian critic would not be won over to Tchaikovsky's music until 1897, when [[Gustav Mahler]] conducted the first performance of ''[[Yevgeny Onegin]]'' in [[Vienna]].</ref> | |||

<ref name="note6">From [[Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov]]'s book {{bib|1934/13|50 лет русской музыки в моих воспоминаниях}} (1934), quoted here from {{bib|1980/63}} (1980), p. 238; English translation in {{bib|1993/33|Tchaikovsky Remembered}} (1993), p. 66.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note7">See also [[Letter 490]] to [[Modest Tchaikovsky]], 2/14 August 1876.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note8">Quoted in {{bib|1997/95|Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского ; том 2}} (1997), p. 244.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note9">[[Letter 4720]] to [[Pyotr Jurgenson]], 1/13 July 1892.</ref> | |||

<ref name="note10">Liszt's letter to Tchaikovsky is included in {{bib|1970/6|Чайковский и зарубежные музыканты}} (1970), p. 41-42.</ref> | |||

</references> | </references> | ||

[[Category:People| | [[Category:People|Liszt, Franz]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Composers|Liszt, Franz]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Conductors|Liszt, Franz]] | ||

[[Category: | [[Category:Pianists|Liszt, Franz]] | ||

Latest revision as of 11:32, 17 August 2023

Hungarian composer, pianist, conductor, and teacher (b. 22 October 1811 [N.S.] in Raiding [now Doborján], near Sopron; d. 31 July 1886 [N.S.] in Bayreuth), born Liszt Ferenc.

Tchaikovsky and Liszt

Although Liszt — like Berlioz, Meyerbeer, and to some extent Wagner — was one of the 'forbidden' modern composers whose works Tchaikovsky and Herman Laroche would play through as students at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, in defiance of the classical precepts of their teachers, it seems that Tchaikovsky never really warmed to Liszt's music. Laroche himself would emphasize, when recalling his late friend's musical sympathies, how "Pyotr Ilyich came slowly, waveringly, and distrustfully to Liszt [...] Of the symphonic poems only Orfeo roused any real enthusiasm during his time at the Conservatory. It was only much later that he came to love the Faust-Symphonie, and for the sake of impartiality it is worth adding that Liszt's symphonic poems, which enthralled a whole generation of Russian musicians, exerted but an ephemeral and external influence on the style of his own compositions" [1]. One reason for this distrust towards Liszt may have been his vigorous campaigning for the 'new German school of music', as all such proselytizing in the name of new and radical principles repelled Tchaikovsky's nature (this also partly explains his ambivalence towards Wagner). More importantly, however, Liszt's music was deficient in substance as far as Tchaikovsky was concerned. He made this clear in a letter to Nadezhda von Meck from Rome, shortly after attending a concert in Liszt's honour in December 1881:

The day before yesterday I was at a gala concert in honour of the 70-year-old Liszt. The programme was drawn up exclusively from his works. [...] Liszt himself was present at this concert. It was impossible not to be moved by the sight of this great old man, who was touched and shaken by the ovations which the enthusiastic Italians gave him. However, Liszt's works as such leave me cold: poetic intentions predominate in them over real creative force, colouring over draughtsmanship — in short, despite all their effective packaging, they are marred by an emptiness of inner content. He is the complete opposite of Schumann, whose awesome, mighty creative force was mismatched with a greyish, colourless exposition of the musical ideas [2].

In his obituary of Tchaikovsky, Nikolay Kashkin wrote in similar terms of his late friend's attitude to Liszt: "Pyotr Ilyich could not stand bombast in music, and that is why he did not rate Liszt particularly highly" [3].

Nevertheless, when Tchaikovsky was just starting out as a composer, it was very difficult not to fall under the sway of the new ideas proclaimed by Liszt and his followers — namely, that programme music, with its greater freedom of expression, was the way forward. Thus, in some of his earliest orchestral works Tchaikovsky paid tribute to this craze for music which illustrated a specific subject. This was the case with the symphonic fantasia Fatum (1868), which Laroche sharply criticized in a review for its proximity to the Lisztian model of symphonic poems, with their "sombre and tragic" subjects, as well as their "jarring dissonances and bizarre orchestral effects" that, according to Laroche, were not at all congenial to the nature of Tchaikovsky's talent as it had expressed itself in his First Symphony (1866) [4]. Despite this criticism (which eventually prompted the composer to destroy the score of Fatum), Tchaikovsky never dissociated himself entirely from the programme music championed by Liszt and Berlioz. Indeed, just a year later, when he was still under the influence of Mily Balakirev (who, like the rest of the "Mighty Handful", admired Liszt for his boldness and also for his early support of Russian music in the 1840s), Tchaikovsky would write yet another piece of programme music: Romeo and Juliet (1869). Although this overture-fantasia would eventually become one of Tchaikovsky's most beloved works, both in Russia and abroad, it is interesting that the fiercely conservative Austrian critic Eduard Hanslick attacked the overture after a performance in 1876, calling its author "a disciple of Liszt" and ridiculing the "melodramatic noise and smoke effects" of this "tone-painting", whose subject Tchaikovsky, in Hanslick's view, had borrowed from Shakespeare following Liszt's example [5].

Even if Tchaikovsky would have protested at being bracketed in this way with the 'new' German or even the new Russian school of music, it is significant that he always kept returning to the 'Lisztian' genre of programme music throughout his life (e.g. Francesca da Rimini, Manfred, Hamlet). Likewise, his attitude towards Liszt's music was not as negative as the above letter to Nadezhda von Meck might suggest. In his feuilleton articles during the 1870s Tchaikovsky praised a number of works by the Hungarian composer, especially his religious oratorios, which expressed the "profoundly moving poetry of Christian love", and in the case of the symphonic piece Totentanz [Dance of Death] he actually defended Liszt, a "profound and sensitive artist", as he called him, against those who wished to see nothing but realistic depictions in his music. (References to these articles are listed below.) With regard to Liszt's two piano concertos, however, he seems always to have found them "brilliant but empty". Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov later recalled how he had started humming the theme from Liszt's First Piano Concerto during a walk with Tchaikovsky around Maydanovo in March 1887, and how the latter had then berated him: "Please don't remind me of that play-actor. I can't stand his insincerity and affectation!" [6].

Tchaikovsky first met Liszt at the inaugural Bayreuth Festival in the summer of 1876, and he was delighted to see before him that "wonderful, characteristic grey head", which had always fascinated him on the photographs he had seen of the veteran composer (see Chapter IV of TH 314) [7]. Liszt for his part seems to have appreciated the younger man's music, as we may see from a letter which the cellist Wilhelm Fitzenhagen sent to Tchaikovsky from Wiesbaden in 1879, telling him about a performance there of the Variations on a Rococo Theme: "It gives me great pleasure to be able to report to you that I performed your Variations to a tremendous furore! [...] Liszt told me: 'You played magnificently. This is truly music!', and it is a tremendous compliment that such a thing could be said by Liszt!" [8] Even so, Tchaikovsky himself believed that Liszt was not really an admirer of his music: "I think that he genuinely preferred Messrs Cui and others who went cap in hand to him in Weimar, and whose music he also liked. As far as I know, he didn't feel any particular sympathy for my music" [9].

Nevertheless, in 1880, Liszt made a brilliant paraphrase for piano of the Act III Polonaise from Yevgeny Onegin, which Nikolay Rubinstein was the first to perform in Moscow. Liszt was thereby in effect repaying a compliment which Tchaikovsky had made in 1874, when he arranged for orchestra Liszt's ballad Der König von Thule (a setting of Gretchen's song in Goethe's Faust). So despite his reservations about Liszt as a composer, it must have been very gratifying for Tchaikovsky, during his first concert tour to Leipzig in January 1888, to discover that the young members of the city's Liszt Society (Liszt-Verein) were all enthusiastic admirers not only of his own music, but also that of his colleagues back in Russia (see Chapter VIII in TH 316) — just as Liszt himself had been one of the earliest champions of Russian music in Western Europe.

Tchaikovsky's Arrangements of Works by Liszt

- Der König von Thule, TH 186 (1874) — arrangement for orchestra of Liszt's ballad for voice with piano, S.278 (1843, rev. 1856).

- Preghiera — third movement of Suite No. 4 ("Mozartiana"), Op. 61 (1887) — orchestral arrangement of the second section from Liszt's Evocation à la Chapelle Sixtine, S.658 (1862–65), which was itself a piano transcription of Mozart's chorus Ave verum corpus, KV 618.

General Reflections on Liszt

Bold references indicate particularly detailed or interesting references.

In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles

- TH 268 — Tchaikovsky discusses Liszt's sacred music, praising his "genuinely religious disposition" and comparing it to the masses written by Beethoven, which, like all of the German's symphonic music, were "lyric effusions of sentiment" merely using the words of the liturgy as a pretext.

- TH 269 — praises Liszt for the "richness of his orchestral and harmonic technique" and calls him "a profound and sensitive artist".

- TH 277 — argues that Liszt is one of those composers like Mendelssohn or Balakirev who lacked inventive power but were nevertheless able to "extract everything contained in the embryo of a musical idea" by means of brilliant orchestral effects.

- TH 305 — compares the "morbid pursuit of staggering effects" in Liszt's "bombastic" Dante Symphony with the modest simplicity and beauty of the overture to Mozart's Die Zauberflöte.

In Tchaikovsky's Letters

- Letter 1341 to Nadezhda von Meck, 18/30 November 1879, in which Tchaikovsky writes very critically of a joint work by Borodin, Cui, Lyadov, and Rimsky-Korsakov, the Paraphrases sur un thème obligé, noting that the fact that Liszt had praised it meant nothing:

As far as Liszt is concerned, this old Jesuit responds with exaggeratedly enthusiastic compliments to any work that is sent to him for his venerable perusal. He is essentially a good man and one of very few outstanding artists in whose heart there was never any petty envy or inclination to obstruct his fellow-artists' success (Wagner and, to some extent, Anton Rubinstein are obliged to him for their success; to Berlioz, too, he rendered many services), but on the other hand he is too much of a Jesuit to be capable of being truthful and sincere.

- Letter 1949 to Nadezhda von Meck, 30 January/11 February 1882, in which Tchaikovsky describes a chamber music concert in Rome at which a new string quartet by Giovanni Sgambati was played. Tchaikovsky had found this work awful:

And yet Liszt, who was sitting there in a prominent place, surrounded by a whole bouquet of lady admirers, pretended in the most cunning fashion to go into raptures over it. How I dislike this trait in Liszt! He never says the truth and always praises everything unconditionally. People write to me in their letters that it is wrong of me not to call on Liszt given that we are living in the same city. However, on no account will I ever go and visit him, because to his cloying compliments it is necessary to reply in like, that is with flattery, and that is so loathsome to me!

Views on Specific Works by Liszt

Bold references indicate particularly detailed or interesting references.

In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles

- Années de pèlerinage, Suite No. 1, S.160 (1848–55) — TH 278

- Christus, oratorio, S.3 (1866–72) — TH 268

- Dante symphony, S.109 (1855–56) — TH 305

- The Legend of Saint Elisabeth, oratorio, S.2 (1857–62) — TH 268

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in A major, S.125 (1839, rev. 1861) — TH 287

- Prometheus, symphonic poem, S.99 (1850, rev. 1855) — TH 273

- Totentanz (Paraphrase on "Dies irae"), for piano with orchestra, S.126 (1847, rev. ca.1862) — TH 269

Bibliography

- Письма Петру Ильичу Чайковскому (1958)

- Liszt oder Menter? (1982)

- Is it really Liszt? (1982)

- Is it really Liszt? (1982)

- Uj Liszt-zongoraversený (1983)

- Long lost Liszt Concerto? (1983)

- Liszt—Menter—Čajkovskij. Zur Geschichte des Konzertstücks Ungarische Zigeunerweisen (2006)

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

Not long before his death in 1886, Liszt also sent Tchaikovsky a signed photograph with a brief accompanying letter, which is now preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin (a4, No. 2141) [10].

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ П. И. Чайковский в Петербургской консерваторий (1979), p. 65; English translation in Tchaikovsky remembered (1993), p. 24.

- ↑ Letter 1902 to Nadezhda von Meck, 26 November/8 December–27 November/9 December 1881.

- ↑ Пётр Ильич Чайковский (1980), p. 361.

- ↑ Laroche's review is quoted in An Tschaikowsky scheiden sich die Geister. Textzeugnisse der Čajkovskij-Rezeption, 1866-2004 (2006), p. 48–51.

- ↑ Eduard Hanslick's review is quoted in An Tschaikowsky scheiden sich die Geister. Textzeugnisse der Čajkovskij-Rezeption, 1866-2004 (2006), p. 57–58. At the end of this review he alluded to the example of Liszt's 1858 symphonic poem Hamlet. The formidable Austrian critic would not be won over to Tchaikovsky's music until 1897, when Gustav Mahler conducted the first performance of Yevgeny Onegin in Vienna.

- ↑ From Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov's book 50 лет русской музыки в моих воспоминаниях (1934), quoted here from Из книги 50-лет русской музыки в моих воспоминаниях (1980), p. 238; English translation in Tchaikovsky remembered (1993), p. 66.

- ↑ See also Letter 490 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 2/14 August 1876.

- ↑ Quoted in Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 2 (1997), p. 244.

- ↑ Letter 4720 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 1/13 July 1892.

- ↑ Liszt's letter to Tchaikovsky is included in Чайковский и зарубежные музыканты (1970), p. 41-42.