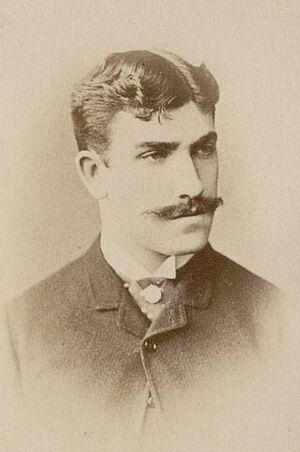

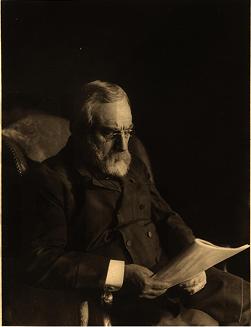

Lucien Guitry

French dramatic actor (b. 13 December 1860 [N.S.] in Paris; d. 1 June 1925 in Paris), born Lucien Germain Guitry.

Biography

Lucien's parents, who were both enthusiasts of the theatre, encouraged their son's theatrical ambitions, and at the age of 15 he was admitted into the Paris Conservatoire (which was then officially known as the Conservatoire de musique et de déclamation), where he joined the class of the veteran comic actor Monrose (real name: Louis-Martial Barizain; 1809–1883). Guitry senior rented a small theatre in the suburb of Saint-Denis for Lucien so that he and his fellow students at the Conservatoire could stage their own performances, and on 7 January 1877 [N.S.] Lucien made his official début there, as Don César de Bazan in Victor Hugo's drama Ruy Blas. Already on this modest stage Lucien played two important roles in comedies by Molière: Alceste in Le Misanthrope and Thomas Diafoirus in Le Malade imaginaire. (Alceste would later become one of his crowning achievements). At the two examinations of the Conservatoire in which Lucien took part, in July 1877 and 1878 respectively, he was, however, awarded only a second prize each time. Nevertheless, in July 1878, the director of the Comedie-Française offered Lucien, who had not even turned eighteen yet, a contract with France's most prestigious state theatre, on the condition that he continued his studies at the Conservatoire for another year. Lucien refused, and signed instead a contract with the Théâtre Gymnase in Paris, which led to his being taken to court by the Conservatoire, because its graduates were obliged to work in state theatres for two years. He would eventually have to pay 10,000 francs in damages to his alma mater.

Undeterred by these adversities, in the autumn of 1878 Guitry made his début at the Théâtre Gymnase as Armand Duval in the famous adaptation of the novel La Dame aux camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils — a role which he performed many times, including alongside the great tragédienne Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) during her tour of London in 1881, but one with which he soon became fed up, as he emphasized in his memoirs: "In Russia this wretched play served as a début vehicle for all the young would-be leading actresses who were dying to be allowed to die of consumption at a quarter to midnight in the role of Marguerite Gautier" [1]. Tchaikovsky, who was then not yet acquainted with the actor, saw Guitry in a performance of Édouard Pailleron's comedy L'Âge ingrat at the Théâtre Gymnase in early January 1879 [N.S.], and in a letter to his brother Modest from Paris he enthused: "I managed to go myself to the Gymnase and to see a delightful new play, L'Âge ingrat, which was wonderfully performed. This was the only production which I really enjoyed" [2].

On 10 June 1882 [N.S.], during a second tour of London with Sarah, Guitry married a fellow actress, Marie-Louis-Renée Delmas (de Pont-Jest; 1858–1902), in spite of the opposition of her father, a minor novelist. After returning to Paris later that summer, he cancelled his contract with the Théâtre Gymnase and accepted an engagement with the French company at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg. This move was undertaken largely for the sake of the lucrative salary offered by the Russian Imperial Theatres (some 40,000 francs a year), and during his nine seasons in Russia, Guitry would appear in a host of roles at the Mikhaylovsky because it was the practice there to put on a new play every week. Guitry and his wife would spend winter and spring in Saint Petersburg, returning to France for the summer months. Of the four sons born to them over the following years, only two survived infancy. The eldest, Jean-Louis-Edmond, was born in Saint Petersburg on 22 February/5 March 1884, and he later worked as an actor and journalist until his death in a car accident in France in 1920. The younger son, Alexandre-Pierre-Georges, was also born in Saint Petersburg, on 9/21 February 1885, and under the name of Sacha Guitry he would go on to become a famous playwright, stage and film actor, and director.

During his years in Russia (1882–91), Guitry liked to take part in Saint Petersburg high life, and he soon gained a reputation there as something of a Casanova. A certain Mademoiselle Angèle, a fellow actress at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre, became his mistress, and this eventually led to his being divorced from his wife in 1890. Although Sacha stayed with him in Russia for a while, even appearing in some pantomimes at the Gatchina palace together with his father, custody of the boy passed to his mother, and Guitry was estranged from his talented son for several years.

Tchaikovsky and Guitry

Among Guitry's most acclaimed roles in Russia were Ruy Blas, Hamlet (see below), Armand Duval, and Coupeau in the stage version of Émile Zola's novel L'Assommoir. However, it was in the role of Jack in an adaptation of Alphonse Daudet's eponymous novel that Tchaikovsky first saw Guitry on the stage of the Mikhaylovsky, in December 1882. In a letter to his brother Anatoly he shared his impressions: "Yesterday I saw the drama Jack at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre, and I was staggered by the acting of genius I saw from the new actor Guitry" [3]. Significantly, it had been Anatoly's twin brother Modest who had urged the composer to see the new star of the French theatre in Saint Petersburg [4]. Modest, who, despite having assumed the earnest task of educating Nikolay Konradi, was still drawn to the glitter of high society, eventually managed to make the acquaintance of Guitry in one of Saint Petersburg's aristocratic salons [5], and it was he, too, who introduced his elder brother to the actor. On 30 March/11 April 1885, Tchaikovsky witnessed another memorable performance by Guitry in the role of Edmund Kean in Alexandre Dumas père's play inspired by the great English actor's life: Kean, ou Désordre et génie [6]. This performance, according to Modest in his biography of the composer, served as the catalyst which led Tchaikovsky eventually to undertake what would become the overture-fantasia Hamlet: "Once, while under the effect of the strong impression produced by Lucien Guitry's splendid acting in Kean, where, among other things, there is a scene from Hamlet, Pyotr Ilyich remarked that he would gladly write the music to this tragedy if Guitry were to act in it" [7]. In fact, Tchaikovsky committed himself to this project in a remarkable letter which he sent to Guitry two days after his performance as Kean (almost certainly his very first letter to the actor):

I have thought a lot about you these last two days, and I shall take the liberty of telling you what is the outcome of my deliberations regarding your future as an artist. It is necessary that at your next benefit performance you should appear in a Shakespeare role — that of Romeo, or Hamlet. It is necessary, because the current repertoire does not offer sufficient scope for you to deploy all the resources of your talent, which is as original and appealing as it is earnest and grave. It is only once you have played Shakespeare that your talent will be appreciated at its true value ... [I] promise you formally that for your next benefit performance, in the event that you should play Hamlet or Romeo, I shall write an overture and entr'actes specially tailored to the resources of the orchestra at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre. It will be a great pleasure for me, and I shall be proud to participate a little in your triumph [8].

Tchaikovsky, however, did not get round to fulfilling this promise until almost six years later when he wrote his incidental music for Hamlet (see below).

During his month-long stay in Paris in the summer of 1886, Tchaikovsky much appreciated the company of Guitry, then on holiday in his native France together with Mlle Angèle. The actor helped him to get out of some unwelcome social appointments, as he noted in his diary: "Guitry (what a smart and wonderful man) advised me not to go tomorrow to Marmontels class [at the Conservatoire] and even drafted a letter for me" [9]. Guitry also helped Tchaikovsky to escape (for the time being) from the librettist Léonce Détroyat, who was determined at all costs to collaborate with the composer on a French-language opera, as we learn from a letter to Modest a few days later: "The writer Monsieur Détroyat is pestering me with a libretto on a Russian subject and if it hadn't been for Guitry (a wonderful and most intelligent person), I don't know how I would have got rid of him" [10]. Later that autumn, when Guitry had resumed his duties at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre, Tchaikovsky dined with him and Mlle Angèle a number of times, and on his return to Maydanovo from the capital he wrote to Yuliya Shpazhinskaya: "Among the people from other spheres with whom I have spent the most time during this visit to Petersburg I should like to single out the French actor Guitry. I have come to like him very much. In addition to his tremendous talent as an actor he is also a person who, thanks to his intellectual maturity and learning, stands infinitely higher than the usual level of those belonging to his profession" [11].

As Modest observed in his biography of the composer: "[From 1885 onwards] Pyotr Ilyich was very good friends with the French actor Guitry, whom he at first came to like on account of his great talent, and whom, after getting to know him better, he also liked for his brilliance, wit, fine powers of observation, for the pleasure which his declamation afforded him, for his affectionateness and his purely Russian expansive nature" [12]. The appreciation was entirely mutual, and if Tchaikovsky concluded another letter to Guitry in the spring of 1885 with these words: "Do not forget me, believe in my unshakeable friendship and admiration for your great and beautiful talent" [13], the Frenchman sent his photograph to Tchaikovsky two years later with the following no less eloquent inscription: "To Pyotr Tchaikovsky from the most fanatic of his admirers and the most loving of his friends. Lucien Guitry. Saint Petersburg, 5 November 1887" [14]. In his letters to the composer, Guitry expressed his sincere joy at seeing how Tchaikovsky's music was finding increasing appreciation both in Russia and abroad:

- "My dear great friend: You can imagine the joy which I feel on hearing from all quarters about the enormity of your triumph yesterday. No one can be happier than me about it" (from a note sent shortly after Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his opera The Enchantress at the Mariinsky Theatre on 20 October/1 November 1887).

- "I found out from Modest about the fine reception which you were given in Leipzig, and all of us here rejoiced at it ... I've been to hear The Enchantress once again: it is as before, and ever more so, my favourite opera; it is wonderful" (from a letter sent from Saint Petersburg on 25 January/6 February 1888 to Tchaikovsky, who was on his first conducting tour of Western Europe).

- "I am overjoyed by your triumphs, my dear Great Friend. You can imagine the unadulterated pleasure which I feel on seeing such a colossal personality as yours receiving the confirmation of universal success. Well, then, add to this the fact that the homage paid to this admired genius comes from my compatriots, and you will have an idea of the satisfaction I experienced when reading about the reception you were accorded in France" (from a letter sent from Saint Petersburg after 3/15 March 1888 to Tchaikovsky, who had recently conducted two Châtelet concerts in Paris).

- "Mita [Dmitry Aleksandrovich Benckendorff (1845–1917), a Russian aristocrat and amateur painter] told us — Angèle and me — about the rehearsal of The Queen of Spades. Our eyes became moist with tears as we thought about our great man — 'the little old man', as Sacha says — and his new masterpiece" (from a letter written in Paris on 17 September 1890 [N.S.]).

- "Angèle embraces you. Yesterday we went to see The Sleeping Beauty. The auditorium was packed and it was a great success. Tonight we're going to see Mazepa" (postscript to a letter written in Saint Petersburg on 4/16 October 1890) [15].

In late January/early February 1888, Guitry wrote to Tchaikovsky to inform him that Grand Duchess Mariya Pavlovna (1854–1920), a sister-in-law of Tsar Alexander III, wanted to organize a gala charity production in the Mariinsky Theatre in late March/early April. Among other things, she wanted Act III from Shakespeare's tragedy Hamlet to be staged, with Guitry in the title role, and with an overture by Tchaikovsky. Guitry, however, realised that the composer might not have enough time to write a whole overture by that deadline, and he asked him instead for an entr'acte to fill the interval between the Players' Scene and the scene in the Queen's closet where Hamlet kills Polonius [16]. Although Guitry subsequently wrote to Tchaikovsky to tell him that the production had been cancelled, the composer was so captivated by the idea of setting Hamlet to music — something he had already considered twelve years earlier — that in the course of the summer he proceeded to write his overture-fantasia on the subject. Although the original impetus had come from Guitry, whose performance as Hamlet in Kean three years earlier had, moreover, so impressed Tchaikovsky, the overture-fantasia Hamlet was dedicated not to him, but to Edvard Grieg.

Two years later, however, Tchaikovsky fulfilled his earlier promise to write proper stage music for Hamlet for the farewell performance which Guitry was due to give at the Mikhaylovsky Theatre on 9/21 February 1891, and for which the actor had chosen Shakespeare's tragedy in a French translation by Alexandre Dumas père and Paul Meurice. Together with a copy of the play, in which he had marked all the points at which he wished the music to set in, Guitry sent Tchaikovsky a letter with more detailed instructions, adding jestingly at the end that the last thing he wanted was to appear "like a second Détroyat" in the composer's eyes, and so he asked him not to trouble himself too much over this music [17]. The performance of Hamlet with Guitry in the title-role took place as scheduled on 9/21 February 1891 with Tchaikovsky's incidental music. In a letter to his brother Anatoly the composer reported: "My music to Hamlet, put on for Guitry's benefit, went down very well with everyone. Guitry was superb" [18]. Still, Tchaikovsky himself didn't set great store by his incidental music — perhaps because he had recycled a number of earlier works when writing it — and indeed he would later rate the stage music for Hamlet written by his friend George Henschel higher than his own [19]. Guitry, however, was delighted with the music for his farewell performance in Russia, and, once he had returned to France for good, he sent Tchaikovsky, as a token of his gratitude, a bronze cockerel by the French sculptor Auguste Cain (1822–1894). This present can still be seen today in the composer's living-room at the Klin House-Museum.

On his return to Paris in 1891, Guitry was engaged by the Théâtre de l'Odéon, although he also worked in other theatres and went on tour to London. It is likely that he stayed in touch with Tchaikovsky, even if no letters exchanged between the two men after 1891 have come to light as yet. On 4 January 1893 [N.S.], during his penultimate visit to Paris, Tchaikovsky had the chance to see Guitry on the stage again, as Agathos in the adaptation made by Maurice Donnay (1854–1945) of Aristophanes's comedy Lysistrata, but he did not take away a favourable impression: "Yesterday I went to see Lysistrata. It is a very talented play, witty and extremely bawdy, though at times rather boring. Guitry seemed rather loutish to me, and on the whole I didn't like him" [20]. Guitry, on the other hand, always held Tchaikovsky in the highest regard, and after his death he wrote to the composer's brother Modest: "Poor Pyotr. A cherished, noble heart ... I am experiencing a deep sorrow which words cannot convey ... Together with you I mourn this simple and great man who has only just left us" [21].

In December 1901, Guitry was appointed stage director at the Comédie Française by ministerial decree, but he left this post already in July of the following year. From 1902 to 1910 he was director of the Théâtre de la Renaissance, where he also continued to act, with such eminent literary friends as Anatole France (1844–1924), Paul Bourget (1852–1935), and Edmond Rostand (1868–1918) writing plays for him. In 1911, he embarked on his first tour of South America — a demanding enterprise that he repeated in 1912 and 1916. Guitry kept up his reputation as a lady-killer, but around 1906 he married again (his second marriage, however, also ended in divorce in 1918). Long since reconciled with his two sons, he would give one of his finest performances when he created the title-role in the play Pasteur (1919) by his youngest son, Sacha Guitry (1885–1957).

In the course of a career that spanned fifty years, Lucien Guitry acted in a total of 144 plays (with 73 of these roles having been written specially for him), and he appeared on the stage in over 12,000 performances. Considered the most prominent French actor of his time, Guitry was noted for the sobriety and naturalness of his acting. These qualities came to the fore when, in 1922, to mark the tricentenary of Molière's birth, he mounted a production of Le Misanthrope and, almost 45 years after his first attempt, he again took up the role of Alceste. Guitry identified strongly with this character, whose loathing of falsehood and vanity he shared, and his interpretation of Alceste came as a revelation to the Parisian public. On the whole, Guitry revered Molière, in whom he saw the patron saint of all actors, because throughout his life he had defied all adversities in order to dedicate himself to the stage [22].

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

3 letters from Tchaikovsky to Lucien Guitry have survived, dating from 1885 to 1888, and have been translated into English on this website:

- Letter 2677a – 1/13 April 1885, from Saint Petersburg

- Letter 2680a – 8/20 April 1885, from Moscow

- Letter 3710a – 27 October/8 November 1888, from Frolovskoye

8 letters from Guitry to the composer, dating from around 1887 to 1890, are preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin (a4, Nos. 605–612).

Biography

External Links

Notes and References

- ↑ Lucien Guitry published his memoirs, under the title Mes mémoires, in the newspaper Candide between March and June 1924. After his death these were reprinted elsewhere, together with some previously unpublished chapters. As we have not yet been able to access these earlier publications, the memoirs of Lucien Guitry are cited here from the extracts included by his son in a lavishly produced book: Lucien Guitry. Sa carrière et sa vie, racontées par Sacha Guitry et illustrés de photographies de Ch. Gerschel (1930), p. 89. An abridged version of the latter can be found in the following more readily available paperback edition: Pièces en un acte suivies de Lucien Guitry raconté par son fils (2000). Surprisingly, when writing about his father's life and career, Sacha Guitry did not mention his friendship with Tchaikovsky at all, and so it would be essential to turn to the original text of Mes mémoires.

- ↑ Letter 1035 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 22 December 1878/3 January 1879. The fact that Lucien Guitry was acting in the performance attended by Tchaikovsky has been established by Galina Belonovich in Французский драматический театр в жизни Чайковского (2003), p. 144.

- ↑ Letter 2174 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 15/27 December 1882.

- ↑ See also the postscript in Letter 2156 to Modest Tchaikovsky from Kamenka on 8/20 November 1882: "I am very curious about your Guitry", which suggests that Modest, who was himself a theatre-lover and aspiring playwright, had written to his brother enthusiastically about Guitry's performances.

- ↑ See also the following entry in Modest's diary, made on 9/21 April 1886, in which he reproaches himself bitterly for his many 'faults', including his hankering "to be patted on the head" by various celebrities: "...Why, isn't vanity my third god, the one that causes me to hang around, against my will and feeling quite bored, in the company of Guitry and others..." — quoted from Пётр Чайковский. Биография, том II (2009), p. 251.

- ↑ See Французский драматический театр в жизни Чайковского (2003), p. 144.

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1997), p. 285.

- ↑ Letter 2677a to Lucien Guitry, 1/13 April 1885.

- ↑ Diary entry for 6/18 June 1886. Here quoted from The Diaries of Tchaikovsky (1973), p. 85–86.

- ↑ Letter 2971 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 11/23 June 1886.

- ↑ Letter 3093 to Yuliya Shpazhinskaya, 10/22 November 1886.

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1997), p. 12.

- ↑ Letter 2680a to Lucien Guitry, 8/20 April 1885.

- ↑ Quoted (in Russian translation only) in Чайковский и зарубежные музыканты (1970), p. 113, n. 1, as well as in П. И. Чайковский. Забытое и новое, вып. 2 (2003), p. 144. The abovementioned photograph is reproduced in the latter publication, together with other photographs of Lucien Guitry and his family which belonged to Tchaikovsky and his brother Modest (p. 423–424).

- ↑ These letters are included in both the original French and in Russian translation, in Чайковский и зарубежные музыканты (1970), p. 209–212, p. 107–113. It is worth noting that Guitry uses "tu" ('thou') in his letters to the composer, which reflects their close friendship.

- ↑ Letter from Lucien Guitry to Tchaikovsky, 25 January/6 February 1888. See Чайковский и зарубежные музыканты (1970), p. 209–210 (original French text), p. 108–110 (Russian translation).

- ↑ Letter from Lucien Guitry to Tchaikovsky, 4/16 October 1890. See Чайковский и зарубежные музыканты (1970), p. 212 (original French text), p. 111–112 (Russian translation).

- ↑ Letter 4329 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 12/24 February 1891.

- ↑ See letter 5020 to Michał Hertz, 23 August/4 September 1893.

- ↑ Letter 4836 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 24 December 1892/5 January 1893.

- ↑ These brief extracts from Lucien Guitry's letter to Modest Tchaikovsky are quoted (in Russian translation) in Чайковский и зарубежные музыканты (1970), p. 108.

- ↑ See S. Guitry, Pièces en un acte suivies de Lucien Guitry raconté par son fils (2000), p. 800.