Georgy Tchaikovsky

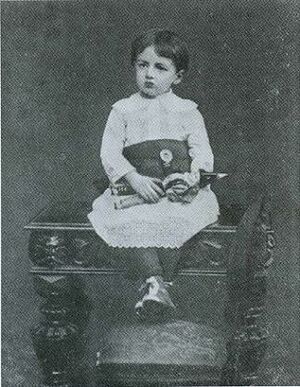

Nephew and godson of the composer (b. 8 May 1883 [N.S.] in Paris; d. 1940 in Belgrade), baptised Georges-Léon Davydov; known after 1886 as Georgy Nikolayevich Chaykovsky (Георгий Николаевич Чайковский). Known affectionately to the composer — as well as to his adoptive parents, Nikolay Tchaikovsky and his wife Olga — as "Zhorzh" (Жорж) or "Zhorzhik" (Жоржик).

Childhood

Georgy was the illegitimate son of the composer's niece Tatyana Davydova (1861–1887) and Stanislav Mikhaylovich Blumenfeld [1] (1850–1898 [2]), a graduate of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory who from 1883 worked as a piano teacher at the Kiev Institute for Girls of the Nobility but also gave piano lessons to the children of Lev Davydov and his wife Aleksandra at their house in Kamenka. After having been seduced by her teacher, Tatyana left Kamenka for Saint Petersburg in order to conceal her pregnancy from her parents and then in January 1883, with the help of her uncle Modest, she went to Paris where the composer was staying at the time working on the orchestration of Mazepa.

Tchaikovsky, later joined in Paris by Modest, supported his niece both morally and by ensuring that she received good medical care during the later stages of her pregnancy and her confinement. Shortly after the boy's birth on 26 April/8 May 1883 Tchaikovsky wrote to Modest, who had by then left Paris: "Already yesterday I began feeling a kind of affection for this child, who has been the cause of so much trouble to us, a desire to be his protector. Just now I felt this ten times as strongly and told Tanya that for as long as I live she need not worry on his account" [3]. Over the next few days his affection did nothing but intensify and he informed Modest in another letter that he was seriously thinking of taking the boy with him to Russia the following year [4]. For the time being, however, Tchaikovsky left Paris on 11/23 May 1883 having given his niece 3000 francs to pay for the services of a wet nurse, as well as to arrange for the boy to be handed over to the care of a foster family, the Auclairs, who lived in Bicêtre on the outskirts of Paris. Soon after his return to Russia, Tchaikovsky started making regular monthly payments of 250 francs to the Auclairs.

During his next visit to Paris in February/March 1884 Tchaikovsky attended the christening of Georges-Léon at the Bicêtre Hospital (12/24 February). Though taken aback at first by the boy's physical resemblance to his father in some respects, the composer was nevertheless delighted to see him again and his paternal instincts manifested themselves in a number of letters in which he shared his concerns with Modest: "I have now decided to start saving in earnest — after all I now have an heir. On the whole Zhorzh's fate worries me very much. What should I do with him? When should I take him to Russia?" [5]. In November/December that year he paid another short visit to Paris to see how Georges was getting on in the care of the Auclairs. In the summer of 1885, Tchaikovsky asked his publisher Pyotr Jurgenson to travel to Paris to initiate arrangements for having Georges brought to Russia, but the boy's mother, Tatyana Davydova, pleaded with her uncle to wait at least one more year before separating him from his foster family in Bicêtre to which he had evidently become attached.

Events took a different course, however, when shortly after attending, in August 1885, the First International Railway Congress in Brussels the composer's older brother Nikolay Tchaikovsky went to Paris with his wife Olga specially for the purpose of getting to know the two-year-old Georges. The boy made a favourable impression on Nikolay, as he confessed in a letter to the composer: "Zhorzh at once manifested his liveliness by breaking off the leg of the toy horse that we had brought him [...] He runs around and prattles like a five-year-old. [...] He is constantly fidgeting, shouting and bustling about. [...] He looks like a healthy and cheerful child" [6]. After Nikolay and Olga, who had no children of their own, expressed their desire to adopt Georges the composer undertook to help them with all the formalities that were necessary so that the boy could leave France. It seems that he had by then realised that he was not in a position to bring up Georges himself, and that it would be better for him to be adopted by Nikolay. This would still allow him to see the boy regularly and to provide financial support for his education.

Tchaikovsky arrived in Paris in May 1886 and at once set about obtaining a birth certificate for Georges and consulting with officials at the Russian Embassy. He was optimistic about the whole affair, but, as he confessed to Modest, he was worried that if Lev Davydov and Aleksandra saw Georges once he was in Russia they would guess the truth of his origins because he so resembled his mother [7]. The prospect of a long train journey in the company of such a boisterous toddler, even though he was to be supported by his sister-in-law Olga who arrived in Paris slightly later, also alarmed him somewhat: "A delightful, pleasing and attractive child — but, my God, the trouble he is going to cause us during the journey! He cannot sit still for one second; I have never before seen such a restless and nervous creature. His parental blood manifests itself very strongly. It is impossible to be angry with him because he is so kind, tender and sweet that it makes your heart melt. [...] He prattles away delightfully, but what particularly fascinates me is when he sings, for example, the Marseillaise at the top of his voice" [8]. In the end it was not the journey itself that proved difficult, but the preceding hassle of getting a French passport for Georges since the Russian consul refused to register him on Tchaikovsky's passport. Even so, at the local préfecture where Tchaikovsky and Olga had to present themselves with the boy and his foster-mother Madame Auclair, "[Georges] caused a furore when suddenly in that silent place he started to sing the Marseillaise at the top of his voice" [9].

Tchaikovsky and Olga set off for Russia with Georges on 12/24 June 1886. They were met at the station in Saint Petersburg on 15/27 June by Nikolay, who now took charge of the boy as his soon-to-be adoptive father. On the day before leaving Saint Petersburg for Maydanovo (17/29 June) Tchaikovsky acted as godfather at the ceremony at which the boy was christened Georgy. In a letter to Modest he described that fateful day: "Zhorzh in his little overall sat in my arms, silently and earnestly, but when he was immersed into the font (I immersed him myself) he cried a lot. On the whole he was sad and quiet that day; he was particularly affectionate towards me, and in order to avoid a scene (the other day when I left he was crying desperately), I made off when he couldn't see it" [10].

From the very beginning of his new life in Russia Georgy was constantly reminded by his adoptive parents of how much he owed to his uncle and benefactor. Some two months after the christening Olga informed Tchaikovsky of how Georgy had been eagerly learning some words in Russian in order to surprise him when he came to visit them, and in her letter she enclosed a flower which the boy had picked himself and asked to send to his uncle [11]. On Christmas Eve 1886 [N.S.], Tchaikovsky received a letter from his brother Nikolay which opened with season's greetings that Georgy had asked his father to write for him. Less than two years later, in the summer of 1888, Georgy was already able to scribble the following words himself in a letter that his mother was writing to the composer: "And I also want to congratulate you and to wish you health and happiness, sweet and dear uncle, I kiss you warmly, Zhorzh" [12]. In April 1891 Georgy sent his godfather an Easter card: "My dear Uncle Petya, I hug you tightly and wish you a Happy Easter as well as Happy Birthday. Every day I pray to God for you. 11 April. Zhorzh" [13].

A few weeks later, on Georgy's eighth birthday his parents were able to buy him a bicycle in Moscow on Tchaikovsky's initiative. The composer had provided them with a letter for Julius Block (1858–1934), a music-loving businessman who ran a shop in Moscow which sold imported American and British goods, including bicycles [14]. Block himself selected a handsome bicycle for the boy and gave him a cycling lesson in the Manège. All this was paid for by Tchaikovsky. Georgy thanked his godfather in a letter written jointly with his mother: "How shall I thank you, my sweet, dear Uncle Petia, for the great pleasure which you have given me through this bicycle. I am so, so happy with it, I am learning to ride it, though it is rather hard to start with. I kiss and hug you tightly, dear Uncle, stay healthy and please do definitely come to visit us at Ukolovo as you promised; I'll be waiting for you. Once again I thank you for everything that you are doing for me!! Your Zhorzh" [15].

Well aware that his brother Nikolay was far from well-off, Tchaikovsky sought to provide for the boy's future by naming Georgy, in the testament that he drew up on 30 September/12 October 1891, the sole heir to all the immovable property that might be in his possession at the time of his death. Any capital that he had acquired was also to go to Georgy, with the provision that he was to give the seventh part to his servant Aleksey Sofronov. The royalties from performances of his operas were bequeathed in full to Vladimir Davydov, but on condition that he paid yearly sums to a number of his other relatives, including 1200 rubles a year to Georgy. If Vladimir Davydov predeceased the composer, then according to the testament the royalties from performances of his operas, as well as the copyright to his works, which Tchaikovsky bequeathed solely to Vladimir, would go to Georgy on the same conditions [16]. (In the end, however, Georgy would receive only 100 rubles a month from his uncle's inheritance because Tchaikovsky never acquired any landed estate, and after Vladimir Davydov's suicide in 1906 the administration of all royalties from the composer's works was, in accordance with Davydov's testament, handed over to his uncle Modest).

The Army Cadet

In the last two years of his life Tchaikovsky was able to see Georgy quite frequently, both in Saint Petersburg and Ukolovo. He was also informed regularly of how Georgy was getting on by the boy's parents: in these letters Georgy would often add some lines of his own. In the spring of 1893 Nikolay informed the composer that Georgy, who in addition to cycling had shown an inclination for horse-riding, had passed the entrance exams for the Nicholas Cadet Corps in Saint Petersburg (the preparatory school for the Nicholas Cavalry College) and that he would commence his studies there as a boarder on 1 September [N.S.]. Before that, however, Georgy once again spent the summer in Ukolovo with his parents from where he wrote the following letter to the composer: "My sweet and dear Uncle Petia!! We haven't had any news from you for a long time and don't know where you are now, though in the New Time we did read something about you. We are very, very eagerly expecting you in Ukolovo: please do come to us as soon as you can, my dear Uncle, don't deceive us" [17]. Tchaikovsky did indeed come to Ukolovo that summer, spending ten days there in July, and he was once again pleased to see his nephew: "Zhorzh has grown a lot; he is naughtier and more fidgety than ever before, but he is very sweet" [18]. A few weeks later Tchaikovsky offered to pay the greater part of the fees for Georgy's first year at the Cadet Corps. His mother gratefully accepted this gift, adding in her letter to the composer: "[W]e thank you very much for your constant concern for our dear boy whom we are always urging to particularly honour and respect you" [19].

A few months after Tchaikovsky's untimely death on 25 October/6 November 1893, Nikolay travelled to Klin and removed from the late composer's house a number of letters which Tatyana Davydova had written to her uncle about Georgy, since he was anxious that the truth of his origins should not be revealed. He also asked his brother Modest to hand over to him any other letters concerning the circumstances of Georgy's birth and adoption [20]. Despite these efforts, however, the secret was eventually found out not only by Lev Davydov (the boy's grandfather) but by Georgy himself [21].

It is mainly on the basis of letters from Georgy's parents to Modest Tchaikovsky (d. 1916) and from his own letters to his uncle that we can obtain some information on the following twenty-five years of Georgy's life. Far from providing a complete picture, these letters nevertheless do reveal two principal motifs: Georgy's veneration of Tchaikovsky's memory and an almost continuous 'learning process' on the part of the young man, albeit with priorities and prospects that changed quite a few times over the years.

Georgy was not sent to the Nicholas Cadet Corps in Saint Petersburg as originally planned. Instead, after the family moved to Moscow in 1895, Georgy started his formal education at a modern school (realnoye uchilishche — a secondary school without teaching of classical languages). His parents also made sure to instil in him an interest in music. "On 11 February (together with Zhorzh)," the boy's father wrote to Modest on 14/26 February 1896, "we heard, with sadness and deeply moved, a performance of the 6th Symphony (Pathétique) under the skilful (in my view) direction of Safonov [...] Zhorzh is growing and putting on weight, but he is not finding his studies particularly easy — even with the help of a home tutor" [22].

Although he nevertheless seems to have progressed at the school he was attending in Moscow, in late 1899 Georgy suffered a nervous breakdown and his parents decided to take him back home and let him recover there. Early in the following year, Olga informed her brother-in-law that Georgy had got it into his head to enrol in the seventh form of the Nicholas Cadet Corps in August because "he feels he has what it takes to become a soldier and says he isn't fit for anything else" [23]. In April 1900, Nikolay himself informed Modest that Georgy was preparing intensely for the imminent entrance exams for the Cadet Corps [24]. However, these plans soon changed as Georgy himself decided instead to enrol in the Cavalry College in Tver as a 'volunteer', explaining to his uncle that it was easier to get a place there [25]. Nikolay himself went to Tver (170 km to the northwest of Moscow) to find suitable lodgings for Georgy. Fearing that army life might have a bad influence on the young man, he asked Modest whether it would be a good idea to introduce him to Vadim Peresleni (effectively Georgy's cousin twice removed), who was working as a French teacher at a school in Tver and whom Nikolay described as a "quite decent person" from whom Georgy might learn some good things [26].

In early 1901, however, Nikolay informed Modest that he was not happy with Georgy's ill-defined situation as a 'volunteer' at the Tver college, and that in the spring or summer he would sit the exams held by the Moscow Cadet Corps. With a certificate from that institution he would then be able to enrol in the Elizavetgrad Cavalry College. Nikolay added that both he and Georgy would prefer it if he could study at the Nicholas Cavalry College in Saint Petersburg instead, but that this was only possible for hereditary nobles. Nikolay asked Modest if he could perhaps address a request to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich to grant a special exemption for Georgy if he were to pass the entrance exams [27]. A month later, though, Nikolay informed Modest that Georgy had firmly decided to take the exams for admission into the second year of the Tver Cavalry College. Once he had attained officer's rank Georgy would then be able to choose for himself the regiment in which he wished to serve [28]. The young man seems to have changed his mind, however, for that summer we find him taking (successfully) the exams at the Academy of the General Staff in Moscow [29]. Despite his parents' worries that he would not be admitted to the Academy because there were so few available places, Georgy seems to have attained the coveted officer's rank after all because the following summer (1902) he went to Kursk for some manoeuvres (though it is not clear with which regiment).

In February/March 1903, Nikolay informed Modest that Georgy had been transferred to the Sumy Dragoon Regiment, which was stationed in Moscow, and that he was therefore living with his parents again. With the help of various tutors Georgy was studying in the evenings so as to be able to take the final exams at his old school the following spring and obtain a school-leaving certificate. Thereafter he intended "to enrol in a higher education establishment, preferring (for the time being) the Moscow Agricultural College" [30]. Georgy did indeed successfully pass these exams in May 1904 and shortly thereafter, on 4/17 July 1904, he married Yelena Golovinskaya (1886-1974), a young lady whose family belonged to the nobility of Tver but was then living in Moscow. The couple spent their honeymoon in Yalta, returning to Moscow in the winter where Georgy started preparing for the entrance exams for the Moscow Agricultural College in August the following year [31]. Georgy's young wife was evidently an admirer of Tchaikovsky's music. "Lena is very keen on visiting Klin," he wrote to his uncle Modest during Christmas 1904 [N.S.], "and seeing the house, especially after I told her about Uncle Petia and Klin" [32].

Those plans regarding the Agricultural College did not materialize, however, as in a letter to Modest in the winter of 1905/06 Nikolay informed his brother that Georgy was now attending a civil engineering course at a private college. He also reminded Modest of the young couple's wish to visit Klin: "Yelena has long wanted to spend some time in Klin and to take a look at the house where Petia lived, for she piously reveres his memory. On a number of occasions she has expressed her intention to go there with Zh[orzh], but without your permission she hasn't dared to do so. Your refusal to grant them this modest wish in the winter of 1904 and now not receiving a reply to their telegraphic enquiry has upset the young couple who cannot understand your obstinate reluctance to let them come to Klin. They have both always treated you with great respect and most cordially." Nikolay pleaded with Modest to allow them to come to Klin on Sunday, 14/27 May, when Georgy would be free, and to spend a few hours in the composer's house [33]. It is not recorded whether this visit actually took place.

Engineer

The summer of 1906 witnessed a further change in Georgy's career plans: from a letter his father wrote to Modest in July we learn that he was now being coached by a student of the Moscow Institute of Transport Engineers. This suggests that Georgy had decided to follow in the footsteps of his father, who played a significant role in the development of Russia's railway network. In May 1907, Georgy fulfilled a request from his uncle Modest to take photographs of a number of houses in Moscow where the composer had lived [34]. Later that summer, Georgy announced his intention to continue his studies in Augsburg, in Germany. However, he did not carry out this plan until more than three years later. In the meantime, he continued to take exams regularly every year — including, in March 1910, exams at the Ministry of Transportation in Saint Petersburg. It is not clear whether he was enrolled in any institution during this period or whether he took the exams as an external student each time. From his parents' correspondence with Modest it is evident that Georgy and his wife spent a lot of time in Ukolovo and at the estate of Yelena's family in Matveyevka, so it is very unlikely that he was following a regular course of study. While in Moscow the young couple were able to enjoy the city's rich cultural life, attending, for example, one of Sarah Bernhardt's guest performances in Russia [35].

On 30 November/13 December 1910, Georgy left Russia with his wife intending to gain some work experience at machinery construction factories in Italy and Germany first before enrolling in a higher education establishment in Germany. Since Yelena was suffering from ill health, however, and the doctors in Moscow had urged her to spend the winter in the south, the young couple headed first for the island of Capri, 36 km from Naples [36]. Modest, who knew Italy very well, had recommended Capri to them and he also provided Georgy with an introductory letter to the writer Maksim Gorky (1868–1936), who was then living on the island. On 23 April/6 May 1911, Georgy wrote to his uncle that he would soon start looking for lodgings in Naples for himself and Yelena if his plans to work at a factory there proved feasible [37]. However, just a few days later he informed Modest that he had been unable to find suitable lodgings in the environs of Naples and that his plan was to go to Augsburg and work at a factory there for a while before enrolling in the Polytechnic School in Munich [38]. In August 1911 (while still on Capri) Georgy wrote his uncle a letter in which he explained at length his actions and intentions. This letter is one of the most revealing from a biographical point of view:

In your letter, dear Uncle Modya, you point out that my wish to live abroad, working first in a factory and then at a higher education establishment, is in your view based solely on my wish to obtain an engineer's diploma. That is not quite true. What I, of course, need above all is qualifications, but in machinery construction — the speciality I have chosen and which attracts me the most — it is utterly impossible to educate oneself. It is essential to receive guidance from professors, to have access to workshops, laboratories, special drawing offices etc., all of which it is impossible to get if one stays at home: for this it is absolutely imperative to be at a higher education establishment. Once I have taken a course, obtaining a diploma won't constitute a separate task or goal as such, but will come by itself. Now, in Russia it is impossible to obtain a post without a diploma, for there having that piece of paper, as you rightly call it, is almost always considered incomparably more important than real qualifications. Studying in Russia, in Moscow, so as not to be separated from my loved ones — something which we would of course be very glad to avoid — is something that I cannot do because my school-leaving certificate, as a result of the wonderful Russian laws, is valid only for two years, and so in order to enrol in the Moscow Technical School I would have to sit the secondary school-leaving exam again, i.e. in all the subjects starting from the 1st form. Firstly, this would take up too much time and this is something that at my 28 years of age I have to take great care not to waste, and, secondly, because of my 'old age' it would be almost impossible for me to pass that exam again.

If I were to live in Russia now and look for a post with the qualifications that I have, i.e. a certificate of secondary education and a technician's diploma from the Institute of Transport Engineering, it would not make things better in terms of avoiding separation from my loved ones. For it would be quite impossible to get a post in Moscow: I would have to work in the provinces and during my first years of work I wouldn't be able to get more than a month's leave each year. In contrast, when I start my higher education course in Germany I will be free for three months in the summer each year and we will of course spend those months together with our loved ones. Apart from the summer holiday, during the break between the winter and the summer semester, in March, I will also be free for about a month. It goes without saying that we would gladly make use of that month to visit our loved ones if it were not so expensive. Thus, as you can see, dear Uncle Modya, there is no question here of a separation lasting 4 years. Living abroad we will in fact be able to spend more time with our loved ones than would be the case if I were now working in the provinces in Russia [39].

While on Capri that summer Georgy and his wife studied Italian and they also enjoyed the company of the many Russian artists, writers and students who were also staying there. Though they did not see that much of Gorky, it was at his house that they made the acquaintance of the great Russian bass Fyodor Chaliapin (1873–1938), whom Yelena described as "amazingly nice" [40].

That autumn, Georgy had started working at a factory in Naples. However, after receiving a telegram from his mother on 19 November/2 December 1911 informing him that his father was dying, Georgy immediately set off for Russia. Nikolay Tchaikovsky died two days later: by the time his son reached Moscow the funeral had already taken place. Georgy spent about three weeks at home trying to comfort his mother. He could not stay longer, though, as he explained to his uncle: "My work at the factory, which now, with Papa's death, has become even more essential than before means that I cannot stay in Moscow. So, much as it saddens me, I won't be able to stay with Mama for long; I am also worried about Lena being left all on her own" [41].

The following summer, Georgy and his wife came to Russia and spent two months in Ukolovo together with his mother. Before returning to Italy they also visited Moscow and Klin, where they spent some time with Modest. In January 1913, their son Georgy was born. Not long before this joyful event, Georgy wrote another letter to his uncle which deserves to be quoted at some length:

Lena and I kindly ask you, dear Uncle Modya, to allow us to register you as the godfather. We very much want you to be our child's godfather because of all the Tchaikovskys you are the one closest to us, not just in terms of family ties, but also on account of our feelings for you. If you consent, then you would make us more than just happy [...] I have enrolled in the Naples Polytechnic School, which I am very happy about. In Naples, at the university and the polytechnic there are lots of Russian students — about 200 — and there are two Russian reading rooms/libraries. Not so long ago a concert was held to raise funds for one of these and the takings were quite good. Most of the numbers were from Russian musical works; some of Uncle Petia's romances were also sung. The performers were mainly Italians, though there were a couple of Russians. A performance of Musorgsky's Song of the Flea 'in the style of Chaliapin' put the Italian audience in a most cheerful mood [42].

After the birth of their son (also called Georgy) in January 1913, Georgy and Yelena moved back to Capri, but quite soon, alarmed by the baby's frail health and on the recommendation of the doctors whom they consulted, they decided to try the milder climate of the Austrian Tyrol. They spent the summer and autumn in Sistrans and Innsbruck, staying in the latter city until the end of October. Though the next surviving letters from them to Modest date from 1915 (by which point they were in Kiev), it is likely that they would have returned to Naples and that Georgy resumed his studies at the Polytechnic School. However, when the First World War broke out in the summer of 1914, Georgy and his young family returned to Russia.

Soldier

From a letter which Georgy wrote to Modest on 12/25 February 1915 it transpires that he was then serving with the First Railway Reserve Battalion in Kiev and helping to train new recruits. Both Yelena and their son were there too. In this letter Georgy also expressed his grief over the death of Anatoly Tchaikovsky on 20 January/2 February 1915: "Uncle Tolya was such a wonderful and good person. We grew so fond of him when we got to know him better on Capri last year" [43]. Yelena herself wrote to Modest eleven days later: "We loved the deceased very much; we came to love him particularly during his stay on Capri. What an interesting person he was! Full of life, interested in everything, he could completely captivate everyone he talked to! [...] The war must have taken its toll on our dear one, and if it hadn't been for this war he might still be with us: he would have been able to travel to the south and that would have strengthened his health. [...] On the 20th [of January] he [Georgy] caught a cold during a practice shoot because they had to ride some 20–30 versts [21–32 km] across an open field during a snowstorm. On the 21st he fell ill and had to stay in bed for 18 days, since he had an acute lung inflammation [...] At the end of this week he is hoping to return to the battalion." Yelena further informed Modest that their two-year-old son had been ill with chicken-pox and that she had caught it from him recently [44].

Soon afterwards, Georgy went off to the front, as we learn from another letter Yelena wrote to Modest: "Yury [Georgy] is not with us; he is with the army in the field. Immediately after recovering from his illness he asked to be sent there" [45]. Yelena herself stayed on in Kiev, though in the summer she visited Moscow where she was reunited with her husband, who had been granted a few days' leave [46].

The last extant letter from Georgy in the archive of the Tchaikovsky House-Museum at Klin dates from August 1915. In this letter Georgy presented his uncle with a depressing picture of the situation in Kiev, which it was feared might soon be captured by the advancing German and Austrian forces:

I am actually still in Kiev. I am expecting to be transferred any day now. Meanwhile I have been setting up the equipment that I brought with me from Moscow. How quickly, unexpectedly and sadly are events changing now. Here one sometimes finds out about many details that are characteristic of the reasons for our retreat. It might all have taken a quite different turn if our society had been enlisted much earlier to take part in the defence and if there had been greater transparency [glasnost'].

In Kiev we've gone through a couple of days of monetary panic — to the extent that it was impossible to ride on a tram, as the conductors wouldn't give any change. Some shops didn't open because of fears of plundering. On the streets all kinds of incidents have constantly been taking place in relation to the changing of money. There were fears of a pogrom, but, fortunately, the panic is now gradually subsiding. The atmosphere here is very depressing and grim. In Moscow there is somehow more confidence in the air.

I hug you and wish that you may get better soon. Yours with sincere love, Zhorzh [47].

Final Years

For more than a century afterwards the subsequent fate of Georgy Tchaikovsky and his family remained unknown. In 1947 V. S. Kuznetsova, the sister of Georgy's adoptive mother, recalled that she had last seen Yelena and their son in Alupka (in Crimea) in 1917, adding that the four-year-old Georgy had an Italian nanny and that "he was prattling in Italian" [48]. The last piece of evidence documentary evidence appeared in the address book All Moscow (Вся Москва) for 1924, which contains the following entry: "Tchaikovsky, Georgy Nikolayevich (railway engineer) – Bolshoy Vlasyevsky Lane, 11, flat no. 2" [49]. It is almost certain that this refers to none other than the composer's nephew and godson.

Three different accounts of what happened to Georgy were handed down orally: 1) He went abroad (to Italy) where he died around 1935 [50]; 2) He remained in the Soviet Union where he would later become a victim of the Stalinist repressions and perish in the Gulag system [51]; or, 3) He emigrated to the United States [52].

The uncertainty continued until June 2017, when Tchaikovsky Research was contacted by Nina Navrockaja from the city of Rijeka in Croatia, to say that she appeared to have found the last resting place of Georgy and his family in the city's Kozala Cemetery [54]. Family members confirmed to her that after the First World War, Georgy and Yelena had emigrated to Yugoslavia, first to the city of Trebinje [55], around 27 kilometres from the city of Dubrovnik, before moving to the latter city, which was then home to a large emigrant colony. Georgy's work as an engineer took him to Zemun, a suburb of Belgrade [56], where he died in 1940.

After the death of her husband, Yelena moved with her son to Zagreb, where the younger Georgy (now known as "Gjuro", the local version of his name) was enrolled at the shipbuilding institute, before deciding to study law. The Second World War interrupted his legal training, and he was captured and imprisoned in Germany. After the war Gjuro returned to Zagreb to graduate from law school, and in the early 1950s moved with his mother to the Croatian port of Rijeka [57]

Yelena had her husband's remains transported to the Kozala Cemetery in Rijeka, where they were re-interred. Yelena herself died in 1974, and was buried in the same grave. Gjuro died at Rijeka in 1983, and is buried with his wife Zora (1915-2001) in another part of the cemetery. They were survived by their son Domagoj (born 1952 at Rijeka).

Dedications

In 1893, Tchaikovsky dedicated a short humorous piano piece to his nephew Georgy: Polka de Salon.

Correspondence with Tchaikovsky

3 letters from the composer to his nephew Georgy Tchaikovsky have survived, dating from 1891 to 1892, all of which have been translated into English on this website:

- Letter 4430 – 27 June/9 July 1891, from Maydanovo (addressed jointly to Georgy and his adoptive parents Nikolay and Olga)

- Letter 4468a – 5/17 September 1891, from Maydanovo

- Letter 4718 – 30 June/12 July 1892, from Vichy (addressed jointly to Georgy and his adoptive parents Nikolay and Olga)

6 letters from Georgy Tchaikovsky to the composer, dating from 1886 to 1893, are preserved in the Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin (a4, Nos. 5735–5736, 5766, 5773, 5778 and 5780) [58].

Copyright Notice

Original article — Copyright © 2012 Valery Sokolov, Moscow, Russia

Original English translation — Copyright © 2012 Luis Sundkvist [59]

See our Terms of Use

Notes and References

- ↑ Stanislav's parents were Mikhail Blumenfeld (b. 1823), a teacher of French and music at a secondary school in Elisavetgrad in central Ukraine (now known as Kirovohrad), who was born in the Kiev province but was of Austrian extraction, and Marie Szymanowska, who came from a family of ancient Polish gentry with a large house and estate at nearby Tymoszówka. (Marie's brother was the grandfather of the Polish composer Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937), who was born in Tymoszówka). Stanislav's sister Olga (c. 1859–1937) was the mother of the distinguished pianist Heinrich Neuhaus (1888–1964) and his younger brother Feliks Blumenfeld (1863–1931) was a noted composer, conductor, pianist and teacher. Elizavetgrad, where the Blumenfelds lived, was only a few kilometres from Kamenka, the home of Lev Davydov and his wife Aleksandra. As neighbours the Davydov and Blumenfeld families must have known each other for many years.

- ↑ In earlier publications the year of Stanislav Blumenfeld's death was given as 1897, but recent research has established that he died of heart failure on 6/18 February 1898.

- ↑ Letter 2275 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 25 April/7 May–26 April/8 May 1883.

- ↑ See also letter 2277 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 27 April/9 May 1883.

- ↑ Letter 2444 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 23 February/6 March 1884.

- ↑ Letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to the composer, 11/23 August 1885 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, а4, No. 5756.

- ↑ See also letter 2953 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 16/28–18/30 May 1886.

- ↑ Letter 2957 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 25 May/6 June 1886.

- ↑ Letter 2973 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 16/28 June 1886.

- ↑ Letter 2979 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 19 June/1 July 1886.

- ↑ See also letter from Olga Tchaikovskaya to the composer, 26 August/7 September 1886 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, а4, No. 5650.

- ↑ Letter from Olga Tchaikovskaya to the composer, 25 June/7 July 1888 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, а4, No. 5652.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to the composer, 11/23 April 1891 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, а4, No. 5735.

- ↑ Block also brought Edison's phonograph to Russia and organized a 'phonographic soirée' in January 1890 at which the only known recording of Tchaikovsky's voice was made. See: Polina Vaidman, "Мы услышали голос Чайковского..." ["We heard the voice of Tchaikovsky..."], П. И. Чайковский. Забытое и новое, вып. 2 (Moscow, 2003), p. 393–397. Also available online (in Russian). For more information on Julius Block and his pioneering recordings, see also: [1]

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky and Olga Tchaikovskaya to the composer, 10/22 May 1891 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, а4, No. 5653.

- ↑ The full text of this testament has been published by Ada Aynbinder in Неизвестный Чайковский (2009), p. 274–279.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to the composer, 27 June/9 July 1893 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, а15, No. 160.

- ↑ Letter 4968 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 6/18 July 1893.

- ↑ Letter from Olga Tchaikovskaya to the composer, 13/25 August 1893 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, а4, No. 5655.

- ↑ See also letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 19/31 December 1893 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6672. Published in part in: Polina Vaidman, "Чайковский и его биографии: от века XIX к XXI" [Tchaikovsky and his biographies: from the 19th century to the 21st], П. И. Чайковский. Забытое и новое, вып. 2 (Moscow]], 2003), p. 11–48 (14–15).

- ↑ As is clear from a letter which Georgy wrote to Modest in July 1905 asking if he had remembered his promise to enquire of Dmitry Davydov about "the portrait of my mother in her coffin" — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6348. This pencil portrait of Tatyana Davydova in her coffin is to this day to be found in the composer's study/living room at the House-Museum in Klin.

- ↑ Letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 14/26 February 1896 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6684.

- ↑ Postscript by Olga Tchaikovskaya in a letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, early 1900 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6692.

- ↑ See also letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 5/18 April 1900 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6693.

- ↑ See also letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 1/14 August 1900 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6344.

- ↑ Letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 15/28 September 1900 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6696.

- ↑ See also letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 11/24 February 1901 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6697.

- ↑ See also letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 14/27 March 1901 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6698.

- ↑ See also letter from Olga Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 28 August/10 September 1901 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6558.

- ↑ Letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 23 February/8 March 1901 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6700.

- ↑ See also letter from Olga Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 24 December 1904/6 January 1905 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6560.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 27 December 1904/9 January 1905 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6347.

- ↑ Letter from Nikolay Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 10/23 May 1906 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6705.

- ↑ See also letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 8/21 May 1907 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6352.

- ↑ See also letter from Olga Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 30 December 1908/12 January 1909 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6705.

- ↑ See also letter from Olga Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 6/19 January 1911 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6578.

- ↑ See also letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 23 April/6 May 1911 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10.

- ↑ See also letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 2/15 May 1911 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6366.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 10/23 August 1911 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6369.

- ↑ Letter from Yelena Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 7/20 November 1911 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6369.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 5/18 December 1911 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 15/28 January 1913 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6371.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 12/25 February 1915 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6373.

- ↑ Letter from Yelena Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 23 February/8 March 1915 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6546.

- ↑ Letter from Yelena Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 12/25 March 1915 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6547.

- ↑ See also letter from Yelena Tchaikovskaya to Modest Tchaikovsky, 24 July/6 August 1915 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6548.

- ↑ Letter from Georgy Tchaikovsky to Modest Tchaikovsky, 16/29 August 1915 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, б10, No. 6374.

- ↑ Letter from V. S. Kuznetsova to Yury Davydov, 27 October 1947 — Tchaikovsky State Memorial Musical Museum-Reserve at Klin, Ф. 48, оп. 2, No. 526/2.

- ↑ "Чайковский Георг. Никол. (инж. п. с.) – Б. Власьевский п., 11 кв. 2".

- ↑ This version seems partly to underlie the not entirely accurate account given by Galina von Meck (1891–1985) in her book As I Remember Them (London, 1973), p. 24: "I remember him [Georgy] very well, both as a boy and then later as a young man. Georg knew that Tatyana was his real mother. He always had a portrait of her on his desk. He studied in Moscow and became a mining engineer. Georg married a charming girl who was also an illegitimate child. The two illegitimates emigrated to Italy after the Revolution, settled there and Georg died there. I do not know what happened later to their son." — Polina Vaidman has informed us that in the genealogical table of the Tchaikovsky family drawn up by Lev Davydov, the son of Kseniya Davydova (1905–1992), the life dates of Georgy Tchaikovsky are given as "May 1883–1940 (or 1935?), Italy".

- ↑ In the original version of this article, Valery Sokolov noted that: "From what we have seen of Georgy's character as it is reflected in his letters (and those of his wife) the second version seems the more likely: as a true patriot who had actively sought front-line service during the World War he would have wished to serve his country as a railway engineer even after the Bolsheviks came to power, much as Nikolay von Meck had done. It is even possible that he shared the tragic fate of von Meck, executed in 1929 in the wake of the "Shakhty Trial", if not at the same time then some years later."

- ↑ This version was communicated to Polina Vaidman by Kseniya Davydova: namely that a certain Tchaikovsky once turned up in a shelter for Russian immigrants in New York run by the Tolstoy Foundation (established in 1939 by Aleksandra Tolstaya, the youngest daughter of Lev Tolstoy). The staff at the shelter suspected that it was Georgy Nikolayevich Tchaikovsky who didn't want to have any contact with the Tchaikovsky family.

- ↑ Georgy's year of birth has been incorrectly inscribed as "1884" on his tombstone, rather than 1883. It is not uncommon for such errors to occur when a deceased's birth year is calculated according to his age at death, especially (as in this case) when the inscription appears to have been made many years after the event.

- ↑ We are extremely grateful to Nina Rukavina for sharing this information with Tchaikovsky Research, and for providing us with the photograph of Georgy's tombstone which accompanies this article.

- ↑ Trebinje (Требиње) is now the southernmost municipality and city in the Serbian-speaking district of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but was at that time part of Yugoslavia (1918-1992).

- ↑ Zemun (Земун) was a separate town until 1934, when it was absorbed into the neighbouring city of Belgrade, and is currently one the 17 city municipalities which make up the Serbian capital.

- ↑ Rijeka was formerly known as Fiume, and had briefly (1920-1924) been an independent state after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire, before being absorbed by Italy. As part of the Paris peace treaty between Italy and the wartime Allies, it became part of the Yugoslav state in 1947, and since 1991 had been the third-largest city in Croatia.

- ↑ Including five letters written with his parents.

- ↑ The original version of Valery Sokolov's article on Georgy Tchaikovsky, originally written for P. I. Tchaikovsky. An Encyclopaedia edited by Polina Vaidman (in preparation) was published here in an abridged English version by Luis Sundkvist with the kind permission of the author and the Tchaikovsky House-Museum in Klin. Any citations from the article or from the primary sources quoted therein should indicate clearly the name of the author and the archival reference.