The Voyevoda (symphonic ballad)

The Voyevoda (Воевода) is a symphonic ballad in A minor (TH 54 ; ČW 51) [1], written by Tchaikovsky in September and October 1890, but not orchestrated until September 1891. After the first performance the composer destroyed the full score, but after his death it was reconstructed from the surviving orchestral parts and published as "Op. 78".

Instrumentation

The Voyevoda is scored for a large orchestra comprising 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets (in A), bass clarinet (in B-flat), 2 bassoons + 4 horns (in F), 2 trumpets (in B-flat), 3 trombones, tuba + 3 timpani, military drum + celesta + harp, violins I, violins II, violas, cellos, and double basses.

Duration

There is one movement: Allegro vivacissimo—Moderato a tempo (A minor, 510 bars), lasting around 12 to 15 minutes in performance.

Subject

The Ballad is based on Aleksandr Pushkin's Russian translation (1833) of the Polish poem Czaty: Ballada ukraińska (The Ambush: A Ukrainian Ballad) by Adam Mickiewicz, which was first published in the collection Poezye Adama Mickiewicza (1829).

The work is unconnected to Tchaikovsky's first opera, also called The Voyevoda (1867-68), or the melodrama he wrote for the stage play of the same name in 1886.

Composition

There is very little surviving evidence concerning the origins of The Voyevoda. From Tchaikovsky's letters to Vladimir Davydov, it would appear that the two men had talked to each other about this subject. Tchaikovsky wrote: "I have composed that ballad for orchestra, on the subject of which you disapprove. I want to dedicate all next week to orchestrating it. I assure you that it was a good idea to write this work." [2].

It seems that the ballad was begun in Tiflis in late September/early October 1890. Tchaikovsky wrote to Pyotr Jurgenson on 28 September/10 October 1890: "I am composing a symphonic poem. I shed a few tears" [3]. From the aforementioned letter from the composer to Vladimir Davydov, it follows that by 4/16 October the ballad was prepared in rough, and in the same letter Tchaikovsky stated that he would spend the next few weeks on its instrumentation. But this intention was not then carried out. In a letter to Modest Tchaikovsky of 10/22 October 1890, the composer wrote: "I've finished my ballad is finished, but I'm trying in vain to orchestrate it" [4]. Tchaikovsky's circumstances forced him to put off completing the ballad for almost a whole year. The productions of the opera The Queen of Spades in Saint Petersburg and Kiev, a commission from Lucien Guitry for music to Hamlet, composing the opera Iolanta and the ballet The Nutcracker for the next winter season, and a concert tour of America—all of these postponed the orchestration of the ballad.

On 15/27 January 1891, Tchaikovsky was forced to withdraw from an invitation from Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov to conduct his new work at a Russian symphony concert in the Russian capital later that month. "Forgive me, for God's sake!", he wrote. "I cannot keep my promise regarding the concert on 27 January. I've not written a single note of the full score of "The Voyevoda"! Circumstances were such that it was impossible! Let us leave it until next year" [5]

In a number of letters to relatives and friends dating from June 1891, Tchaikovsky wrote of his intention to begin scoring the ballad [6]. With this in mind, he also asked Pyotr Jurgenson to obtain a new orchestral instrument:

As long ago as last spring I drafted a symphonic poem "The Voyevoda" (Pushkin's ballad), which I'll also be scoring in the summer. Regarding the orchestration of this item, I have a request for you. I found a new orchestral instrument in Paris, something of a cross between a small piano and a Glockenspiel, with a divinely wonderful sound. I want to use this instrument in the symphonic poem "The Voyevoda" and in the ballet. It won't be required for the ballet until the autumn of 1892, but I'll need it for "The Voyevoda" in the forthcoming season, because I promised to conduct this at the Musical Society in Petersburg, and perhaps I'll also be able to perform it in Moscow. It's called the "Celesta Mustel" and costs 1200 francs. It can only be bought in Paris from its inventor, Mr Mustel. I want to ask you to order this instrument. You won't lose anything on it, because you can rent it out at all the concerts where "The Voyevoda" will be played. And thereafter you can sell it to the theatre directorate when it's required for the ballet [7].

In a further letter to Jurgenson of 22 August/3 September, Tchaikovsky wrote:

It was so nice of you to order the Celesta Mustel for me. For God's sake bear in mind that no one besides myself should hear the sounds of this wonderful instrument before it's played in my works, where it will be used for the first time. I'll now be scoring "The Voyevoda" fantasia (after Pushkin's ballad), and this will be played for the 1st time in Petersburg at a Musical Society concert. (I've been invited to conduct a concert there). Besides this, the Celesta will play a large role in my new ballet. If the instrument should arrive in Moscow first, then you must protect it from outsiders, or if it goes to Petersburg then have Osip Ivanovich guard it [8]

Tchaikovsky took up the orchestration of The Voyevoda as soon as he had finished the rough sketches of Iolanta: "Yesterday I completely finished the opera. Tomorrow I shall take up the instrumentation of The Voyevoda", he told Modest Tchaikovsky on 5/17 September 1891 [9].

The scoring of the ballad was completed around 22 September/4 October 1891, as indicated by a letter to Anna Merkling of the latter date, in which the composer reported that he had finished his new symphonic work [10]. On the same day he wrote to Anatoly Tchaikovsky: "I've finished my symphonic ballad, The Voyevoda. I'm very pleased with it. You really must come to that Musical Society concert in Petersburg, which I'll be conducting. This will be in November" [11].

Arrangements

Tchaikovsky transcribed the central section of the ballad as an independent piece for solo piano under the title Aveu passionné.

Performances

The symphonic ballad The Voyevoda was performed for the first time in Moscow on 6/18 November 1891, at a concert organised by Aleksandr Ziloti, conducted by the composer. During rehearsals, the composer appeared to lose faith in his new work, displaying "a sluggish indifference to nuance, and the complete absence of a desire to produce a good performance", according to Nikolay Kashkin [12]. Modest Tchaikovsky recalled that on the day of the concert, "despite the enthusiastic disposition of the audience towards the composer, The Voyevoda appeared to make little impression, which was explained to a significant degree by the 'sloppy' performance of the disgruntled author [13].

Other notable early performances included:

- Saint Petersburg, Tchaikovsky memorial concert, 13/25 December 1897, conducted by Arthur Nikisch.

- New York, [Carnegie] Music Hall, Symphonic Society concert, 14/26 November 1897, conducted by Walter Damrosch

- Saint Petersburg, Russian symphony concert, March 1897

- London, Queen's Hall, 15/28 September 1905, conducted by Henry Wood.

Autographs

After hearing his new work played by the orchestra, Tchaikovsky became extremely dissatisfied with his new work. During the interval, the concert organiser Aleksandr Ziloti recalled that:

Pyotr Ilyich entered the artist's room and, before I could collect myself, he began ripping up the score, saying that "such rubbish mustn't be written". He summoned the orchestra servant and ordered him to bring him all the orchestral parts at once. Seeing his agitation and knowing that the voices were threatened with the same fate as the score, I decided on a desperate course of action and said: "Pardon me, Pyotr Ilyich, I am the concert manager, and not you, and therefore only I can give instructions here", and I ordered the servant to collect up all the orchestral parts immediately and bring them to my apartment. All of this was said so firmly, with just a dose of insolence, that Pyotr Ilyich, as the say, was dumbfounded. He just said quietly, "How dare you talk to me like that?". I answered him: "We will discuss this another time". At that moment visitors entered there room and our confrontation ended there [14]

The bulky manuscript score proved difficult to destroy, and so Tchaikovsky took it away with him to complete this task, as he reported to Vladimir Nápravník a few days later: "The concert was generally successful, but my ballad The Voyevoda turned out to be so wretched, that the other day after the concert I tore it to shreds. It exists no more" [15]. However, three autograph fragments from the full score have survived, and are now preserved in the Klin House-Museum Archive (a1, Nos. 64-66).

Publication

Aleksandr Ziloti refused Tchaikovsky's requests that the parts in his possession should also be destroyed, since he and Sergey Taneyev considered that the ballad The Voyevoda, although weaker than Romeo and Juliet and Francesca da Rimini, was "for all its sins, full of interesting things" [16].

After Tchaikovsky's death, the full score of the ballad was reconstructed from the orchestral parts and published by Mitrofan Belyayev in Leipzig in 1897 as "Op. 78". An arrangement of the ballad for piano duet by Nikolay Sokolov was issued at the same time [17].

Several letters between Mitrofan Belyayev and Modest Tchaikovsky survive concerning the question of publishing the composer's works posthumously, a number of which relate to The Voyevoda [18].

The Voyevoda was published in volume 26 of Tchaikovsky's Complete Collected Works (1961), edited by Irina Iordan.

Critical Reception

After the composer's death, Sergey Taneyev, in one of his letters to Modest Tchaikovsky in 1901, recalled how he had given his views on The Voyevoda to Tchaikovsky soon after the first rehearsal:

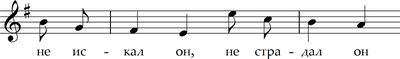

My first impression of The Voyevoda was that the main part of the piece—the central love episode—sounded merely preparatory. Moreover, the musical worth of this central section could not bear comparison with similar episodes in earlier works by Pyotr Ilyich—Romeo, The Tempest and Francesca. It seemed to me that the reception this work received at that time was mistaken. The words of Pushkin's ballad might be sung to this melody, thus:

What this suggests, is that this was not composed as a work for orchestra, but as a romance. Performed without words and on orchestral instruments it produces a somewhat insipid impression, and its impact is greatly diminished [19].

The newspaper critics were much kinder to the work. According to an anonymous reviewer in the Russian Leaflet, "The witty ballad emphasises and depicts in music both the lyrical and epic moments of the plot. It is beautifully developed in thematic and technical respects, but also full of freshness and expressiveness, particularly in those places depicting the lament of the Voyevoda's wife, and the master's words preceding it" [20]. The music critic of the Moscow Register thought that "The music was highly successful in illustrating the content of the programme, shining with a mastery of instrumentation and melodic beauty" [21], while the composer's friend Nikolay Kashkin was rather more guarded in his review for the Russian Register, noting that "The ballad is undoubtedly marked by the high talent of its author" [22].

Tchaikovsky's did not regret his decision to destroy The Voyevoda, as he wrote to his publisher: "Don't feel sorry for The Voyevoda—it got what it deserves. I'm not in the least repentant, because I'm profoundly convinced that this work compromises me. Were I an inexperienced youth then it would be another matter, but a grey-haired old man ought either to move forward (if this is even possible, for example, Verdi continues to progress, and he's nearly 80), or to stay at the heights that he's previously reached. If the same thing happens in future, I'll tear it to shreds again, or even give up composing altogether" [23].

Recordings

- See: Discography

Related Works

- See: Aveu passionné.

External Links

- Internet Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) — downloadable scores

- Text of Mickiewicz's ballad Czaty (Polish)

- Text of Pushkin's translation «Воевода» (Russian)

Notes and References

- ↑ Entitled 'The Voevoda' in TH.

- ↑ Letter 4228 to Vladimir Davydov, 5/17 October 1890.

- ↑ Letter 4224 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 28 September/10 October 1890.

- ↑ Letter 4231 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 10/22 October 1890.

- ↑ Letter 4303 to Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov, 15/27 January 1891.

- ↑ See Letter 4394 to Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov and Letter 4429 to Sergey Taneyev, 27 June/9 July 1891.

- ↑ Letter 4397 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 3/15 June 1891.

- ↑ Letter 4459 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 22 August/3 September 1891.

- ↑ Letter 4469 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 5/17 September 1891.

- ↑ Letter 4478 to Anna Merkling, 22 September/4 October 1891.

- ↑ Letter 4480 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 22 September/4 October 1891.

- ↑ Воспоминания о П. И. Чайковском (1896), p. 150.

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1902), p. 514.

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1902), pp. 514–516.

- ↑ Letter 4545 to Vladimir Nápravník, 11/23 November 1891.

- ↑ See letter from Aleksandr Ziloti to the composer, 21 November/3 December 1891 — Klin House-Museum Archive (a4, No. 1319).

- ↑ See letter from Mitrofan Belyayev to Modest Tchaikovsky, 1/13 April 1896 — Klin House-Museum Archive (б10, No. 396). According to Aleksandr Ziloti, during a meeting in Paris in 1893 he received permission from Tchaikovsky to do as he pleased with the orchestral parts. Following the composer's death later that year, Ziloti decided to return them to his heirs — see Иностранная музыкальная печать сообщает (1896), p. 1288.

- ↑ See letters from Mitrofan Belyayev to Modest Tchaikovsky of 18/30 March, 1/13 April, 13/25 April 1896 and 31 December 1896/12 January 1897 — Klin House-Museum Archive (б10, No. 395–398).

- ↑ Undated letter from Sergey Taneyev to Modest Tchaikovsky, 1901 — Klin House-Museum Archive (б10, No. 5843). The words «Не искал он, не страдал он» = "He did not seek, he did not yearn". According to Modest Tchaikovsky, after hearing the ballad performed for a second time in 1897, Taneyev "bitterly regretted to much too hasty verdict he had then expressed to Pyotr Ilich" — Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 3 (1902), pp. 516.

- ↑ Russian Leaflet (Русские листок), 8 November 1891 [O.S.].

- ↑ Moscow Register (Московские ведомости), 9 November 1891 [O.S.].

- ↑ Театр и музыка, Russian Register (Русские ведомости), 8 November 1891 [O.S.].

- ↑ Letter 4557 to Pyotr Jurgenson, 15/27 November 1891.