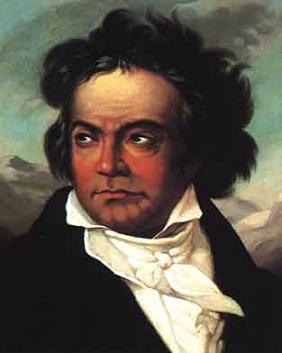

Ludwig van Beethoven

German composer (b. 16 December 1770 [N.S.] in Bonn; d. 26 March 1827 [N.S.] in Vienna).

Tchaikovsky and Beethoven

Tchaikovsky's most well-known declaration about Beethoven is a diary entry made in the autumn of 1886 in which he contrasts the love he had always felt for Mozart, a "musical Christ" who was both divine and human at the same time, with the awe that Beethoven, like God in the Old Testament, instilled in him (the diary entry is quoted below) [1]. However, as Vasily Yakovlev already stressed, when working on the first critical edition of Tchaikovsky's complete works, if one takes account of the many other statements he made about Beethoven, a much more complex picture emerges [2]. Relevant extracts from Tchaikovsky's articles, letters, and diaries are given in the lists below, whereas the introductory paragraphs which follow are an attempt to broach the question of Tchaikovsky and Beethoven drawing on a few other sources as well.

It is true that Tchaikovsky first discovered the ideal beauty of music through Mozart's Don Giovanni, when he heard Zerlina's aria played on an orchestrion at the age of 5, and even more so when, aged 16 or 17, he first heard a full performance of the opera in Saint Petersburg; and, similarly, as he admitted in several letters to Nadezhda von Meck, it was to Mozart that he felt himself obliged for the fact that he had chosen to dedicate his life to music. Nevertheless, in his brief Autobiography of 1889, which only came to light in 2002, Tchaikovsky, whilst still emphasizing the revelation that Don Giovanni had been to him, also recalls how during the first two years that he worked as an official at the Ministry of Justice (1859–61), in his free time he would sometimes sit down at the piano at home:

I would play through my beloved Don Giovanni over and over again, or rehearse some shallow salon piece. From time to time, though, I would set about studying a Beethoven symphony. How strange! This music would cause me to feel sad each time and made me an unhappy person for weeks. From then on I was filled with a burning desire to write a symphony — a desire which would erupt afresh each time that I came into contact with Beethoven's music. However, I would then feel all too keenly my ignorance, my complete inability to deal with the technique of composition, and this feeling brought me close to despair..." (Autobiography.

This declaration suggests that it was Beethoven's symphonies in fact which kindled in the young Tchaikovsky the zeal to write music himself, rather than just escaping from everyday reality into the magical realm of Mozart's opera. Moreover, the feeling of "sadness" which overcame him whenever he heard Beethoven's music is one that would remain with him all his life, and, if around 1860 it was perhaps mainly due to his despair at the thought that he would never be able to write anything similar since he knew nothing of compositional technique, in later years it was certainly the "tragic struggle with Fate and striving after unattainable ideals" expressed in many of Beethoven's works (see the references below) that struck a chord with Tchaikovsky. This affinity he felt with Beethoven and the element of 'struggle' in the latter's life and music is perhaps most interestingly revealed in the additions he made to a compilation of biographical material on Beethoven which he started writing in 1873 but did not complete — 'Beethoven and His Time]]'. These extra observations of his own suggest that Tchaikovsky clearly empathized with some important moments in Beethoven's life: the early loss of his mother [3], the German composer's struggle against adverse circumstances and against the failings of his own character. Thus, far from being merely a remote, awe-inspiring Old Testament God to him, Tchaikovsky recognized in Beethoven a kindred spirit, namely an artist who was deeply aware of the tragedy of human existence, and who sensed that the only true happiness he could find in life was in music [4]. The comparison in his diary between Mozart and Beethoven, at first sight so 'unfavourable' for the latter, might therefore be interpreted, firstly, as a way of expressing how Mozart's music acted like a balsam on his troubled soul as opposed to Beethoven's, which reflected back his own suffering, and, secondly, as an implicit confession of how daunting it was to have to write music in the wake of Beethoven — a feeling that was shared by almost all the other great composers of the nineteenth century!

As Modest Tchaikovsky points out in his biography of the composer, before 1861 his brother's knowledge of orchestral and chamber music was very limited and he could not even list Beethoven's symphonies [5]. In the years that Tchaikovsky was studying at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence (1850–59), there were very few opportunities to attend symphony concerts even in Saint Petersburg, and, besides, his passion for Italian opera had prejudiced him against 'serious' German music. All this changed drastically when he signed up for Nikolay Zaremba's harmony classes in the autumn of 1861. To the amazement of his younger brothers, who until then had only heard him play numbers from Italian operas and fashionable salon pieces on the family piano, Tchaikovsky now started working through tortuous fugues by Bach, and, most importantly, transcriptions of Beethoven symphonies. The one that most fascinated his musically sensitive brother Modest was the Fifth, and Tchaikovsky himself would later draw inspiration from it when writing his Fourth Symphony. The passage quoted above from the Autobiography refers precisely to this period in Tchaikovsky's life when the vocation of a composer had awakened in him, thanks to the ideal realm opened up by Beethoven's music, but there seemed to be no hope of ever realizing his ambitions. This is what threw the young Tchaikovsky into a state of dejection until the opening of the Conservatory in September 1862 changed his life altogether.

Herman Laroche, Tchaikovsky's closest friend at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, later recalled how there they had played through Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, together with various works by Schumann, arranged for piano duet. The student orchestra organized by Anton Rubinstein, which Tchaikovsky was soon able to join after learning to play the flute, often performed symphonies by Beethoven, especially the Eighth, which was to become one of Tchaikovsky's favourites. Laroche, in his memoirs, however, also pointed out that his friend's feelings about Beethoven's music even then had been ambivalent: for example, after one concert Tchaikovsky had described the exchanges between the wind instruments in the final movement of the Eighth as "an unsurpassable stroke of genius", whereas a year later he had merely said that they produced "a comic effect"! [6] (This feature of the symphony is discussed enthusiastically in an article of 1875 — see TH 301.) More generally, according to Laroche, Tchaikovsky, "with the exception of very few works by Beethoven, felt far more respect for him than enthusiasm, and in many regards did not all intend to follow in his footsteps" [7]. Tchaikovsky's attitude, at least as recorded by Laroche, may have partly been a reaction to the cult of Beethoven amongst his teachers at the Conservatory, especially Zaremba and A. Rubinstein. The latter, for example, set him the task of arranging for orchestra one section of the Kreutzer Sonata (see TH 168) and, according to Laroche again, another exercise which Tchaikovsky was given was to orchestrate Beethoven's Piano Sonata in D minor (Op. 31, No. 2) in at least four different versions [8]. The way that Beethoven was constantly held up as a paragon by his teachers very likely provoked Tchaikovsky's rebellious streak, leading him to turn to more modern composers, such as Berlioz and Liszt, as the 'models' for his own orchestral works at first. Nikolay Kashkin, another close friend from the Conservatory, would later also recall how Tchaikovsky at the time was indifferent to chamber music, in particular to Beethoven's late string quartets, one of which (the A minor quartet, Op. 132) made him feel quite "drowsy" [9].

Still, during the first year of his studies at the Conservatory, one of Tchaikovsky's most memorable experiences was getting to hear the six concerts which Richard Wagner gave in Saint Petersburg in February 1863. At these Wagner conducted not just excerpts from his operas but also several symphonies by Beethoven, and a letter to Nadezhda von Meck in 1879 (quoted below) reflects the profound impression which these left on the young Tchaikovsky. Many years later, once he had finally overcome his fear of standing on the conductor's rostrum, Tchaikovsky would himself conduct a successful performance of Beethoven's Ninth at a special Russian Musical Society concert on 25 November/7 December 1889 to raise funds for musicians' widows and orphans [10].

It is true to some extent that, as Laroche remarked, Tchaikovsky did not intend to 'follow in the footsteps' of Beethoven — at least initially. Thus, apart from the First Symphony (1866–68), which cost him a great deal of effort, and String Quartet No. 1 (1871), Tchaikovsky's major creative endeavours in these early years were concentrated on the opera stage and programme music. In this respect it is interesting that Tchaikovsky did not think too highly of Beethoven's single opera Fidelio (except for a few parts, such as Florestan's aria — see the references below), and in his articles he pointed out that Beethoven's mighty symphonic talent was simply unsuited to the requirements of the stage. While working on The Enchantress in 1885, however, Tchaikovsky wrote a letter to Nadezhda von Meck justifying himself in effect for devoting so many of his energies to opera (whereas his benefactress was convinced that he would one day be rated higher than Beethoven not for his operas but for his symphonic works!) [11]. Tchaikovsky argued in this letter that even such great composers of orchestral and instrumental music as Beethoven and Schumann had been drawn to the genre of opera "not out of vanity, but out of the wish to extend their circle of listeners, to act on the hearts of as many people as possible" [12]. Tchaikovsky clearly felt himself to be part of this tradition of communicating, through grandly conceived music, with the people of his country, if not of the whole world — a tradition which was in effect started by Beethoven, since earlier composers accepted that their works would be heard only by a limited audience.

Although Tchaikovsky dismissed the plot of Fidelio as "bourgeois-sentimental" (see TH 269), one particular work linked to this opera, the Leonore Overture "No. 3", was for him one of the greatest wonders of symphonic music. Tchaikovsky repeatedly praised it in his articles of the 1870s, and Alina Bryullova later recalled how at her house in Saint Petersburg, where she had two grand pianos, Tchaikovsky would often ask her and her husband Herman Konradi to join him and Modest in playing various orchestral works transcribed for 8 hands: "He would always start with the Leonore Overture No. 3, which with regard to dramatic intensity he rated above everything else. 'It makes my flesh creep each time,' he said, 'when the trumpet-call rings out in the distance. I think that nowhere else can one find such a staggering effect as this.' But whilst he bowed before the genius of Beethoven, he directed all his love towards Mozart" [13]. Here, too, we find the same juxtaposition of Mozart and Beethoven, again to the detriment of the latter if it is true that in Tchaikovsky's eyes he commanded respect rather than affection! However, Alina Bryullova herself states in these memoirs that during one summer at her family estate in Grankino, she and Tchaikovsky had played through all of Beethoven's string quartets transcribed for piano duet [14]. (Tchaikovsky had bought these arrangements in Clarens at the beginning of 1879 [15].) Such zeal in acquainting himself with Beethoven's less accessible works does suggest that Tchaikovsky's feelings about them were not just limited to awe-struck reverence, and if in that diary entry of 1886 he turns away almost in disgust from the "chaos" which prevailed in the works of Beethoven's final period, a letter written to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich two years later (it is quoted below) shows that Tchaikovsky was capable of appreciating the late string quartets after studying them more closely.

For someone as independent-minded as Tchaikovsky, who liked to reach his own conclusions rather than take anything on trust, the unquestioning veneration of Beethoven which he encountered among many of his teachers and colleagues could not but seem rather suspect. He discusses this issue in an early article of 1871 (see TH 259), observing that it was absurd to maintain that Beethoven was "infallible" in all his works. Now a similar scepticism towards Beethoven was also characteristic of Lev Tolstoy, the Russian writer for whom Tchaikovsky professed the greatest admiration. Tolstoy liked Beethoven's early piano sonatas very much (he was competent enough on the piano to be able to play some of them himself), but whenever he came across professional musicians who spoke about the 'depth' of the German composer's more complex works, especially the final string quartets, that always seemed to be pretentious, insincere talk to him. At his notable meetings with Tchaikovsky in December 1876 it seems that Tolstoy, who liked to provoke arguments, decided to test the latter's sincerity precisely by criticizing Beethoven, whom he supposed to be the idol of all contemporary musicians. In a letter to Nadezhda von Meck a few years later, Tchaikovsky describes the dismay he had felt when Tolstoy during their first conversation suddenly burst out saying that Beethoven had no talent whatsoever! Tchaikovsky had tried to protest, but not very effectively. This was of course not because he agreed with Tolstoy's 'nihilism' in any way, but due to his dislike for quarrelling — especially with a writer whom he so looked up to [16].

The adjectives and nouns which Tchaikovsky uses most often when describing Beethoven and his music in his articles of the 1870s are "colossal", "titanic", and "giant" (that is whilst showing great appreciation for the noble "simplicity" of his themes and "restraint" in the use of orchestral effects). Similarly, in a number of letters Tchaikovsky makes an interesting comparison between Beethoven and Michelangelo as monumental artists — in one case after he had seen the famous sculpture of Moses in Rome [17]. On the other hand, Tchaikovsky speaks almost as often of the "ideal realms" which Beethoven's music opened up but also of the human "struggles" and "suffering" which it conveyed when these yearnings for the ideal could not be fulfilled. In the Fourth Symphony, which contains many of these opposing elements, Tchaikovsky, as he explained in a letter to Taneyev quoted below, sought in part to relive Beethoven's Fifth in his own creative imagination.

Arrangements by Tchaikovsky

- Kreutzer Sonata (1863-64) — an arrangement for orchestra of the exposition from the opening movement of Beethoven's Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major, Op. 47 (1803).

General Reflections on Beethoven

Bold references indicate particularly detailed or interesting references.

In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles

- TH 259 — Tchaikovsky first states that expressing "unquestioning astonishment" at every one of Beethoven's works would be insincere, but emphasizes that some of his symphonic works were indeed incomparable; lists among the essential qualities of Beethoven's music the "noble simplicity of his themes", "logical thematic development", and "moderation in the choice of orchestral effects"; points out that the Eighth Symphony was unusual in that, unlike so many of his works, it irradiated "joyful" feelings throughout.

- TH 266 — refers to Beethoven as "this greatest of all composers" and observes that some of his finest works (the string quartets dedicated to Razumovsky and Golitsyn) belonged to the "humble" genre of chamber music, thanks to his skill in "incredibly rich polyphonic development".

- TH 268 — gives an enthusiastic description of the Eroica as the symphony in which "the immense, astounding force of Beethoven's creative genius" had revealed itself fully for the first time; in a discussion of Liszt's oratorios, Tchaikovsky observes that Beethoven's masses were not really religious works, but, like his symphonies, were "poetically intensive effusions of sentiment", permeated by the same "spirit of despair and struggle" (Tchaikovsky also makes the same point in TH 273); remarks that Beethoven was a "purely subjective" genius.

- TH 269 — Tchaikovsky criticizes the "bourgeois-sentimental" plot of Fidelio, which, except for a few numbers (e.g. Florestan's aria) simply could not stand comparison with Mozart's operas in his view; but describes enthusiastically the Leonore Overture "No. 3" as one of the most "colossal" works of symphonic music ever written!

- TH 275 — in this unfinished compilation of material on Beethoven's life and character, drawn from Alexander Wheelock Thayer's pioneering biography, Tchaikovsky inserts several important observations of his own, which suggest that in some respects he identified with Beethoven.

- TH 285 — Tchaikovsky describes the famous andante of the Piano Concerto No. 4 as one of the most powerful ideas ever expressed in music: the struggle of the human soul with "the inevitable blows of Fate".

- TH 287 — in a brief discussion of the Second Symphony, Tchaikovsky notes that it was a work written still largely under the influence of Mozart, and that its "carefree merriness" was worlds away from the motifs of "hopeless disillusionment" and "desperate striving towards a lost ideal" which filled Beethoven's later works.

- TH 295 — criticizes the Consecration of the House overture as being dry and empty and unworthy of the level which Beethoven attained in his final period, "that period in which otherwise the most colossal works of this musical giant sprung forth".

- TH 296 — gives an enthusiastic discussion of the Seventh Symphony, noting in particular how the famous slow movement revealed "an ideal world of eternal beauty and harmony", and praising "the richness of Beethoven's creative fantasy" and his amazing mastery of thematic development and instrumentation.

- TH 299 — makes a very interesting comparison between Berlioz and Beethoven, observing how the latter was able to construct "a tremendous musical edifice" from a simple idea.

- TH 301 — Tchaikovsky compares the consistently "joyful and festive" mood of the Eighth Symphony with the "unearthly, ideal" kind of joy expressed in the great choral finale of the Ninth, which only left one sadder afterwards when returning back to earth; reflects on the "sorrow and despair" due to "unrealisable hopes and unattainable ideals" which Beethoven generally expressed in his music.

- TH 304 — includes some interesting observations in passing about the works of Beethoven's final period, which "would never be fully accessible" even to a musically competent audience, because of their "imbalance of form".

- TH 310 — argues that Beethoven had stepped out of his element when writing the opera Fidelio and was unable within the constraints of that genre to unfold the "astonishing, inexhaustible originality" which his other works were bursting with; observes how the most beautiful and outstanding moments in Fidelio were of a symphonic nature; dwells again on the "incomparable" perfection of the Leonore Overture "No. 3".

- TH 311 — before discussing the "incomparable and thrilling" Fourth Symphony with its effusion of joyful feelings, Tchaikovsky reflects on how different the rejoicing in the final movements of the Fifth and Ninth symphonies was, since in the earlier movements of those two works Beethoven had "conveyed with such staggering truthfulness the torments of the isolated human soul in its struggle with Fate".

In Tchaikovsky's Letters

- Letter 517 to Sergey Taneyev, 2/14 December 1876, in which Tchaikovsky tells his former student not to let himself be discouraged by all the criticisms Anton Rubinstein had made of a piano concerto he had composed:

I cannot think of any musical works (with the exception of some by Beethoven) about which one could say that they are completely perfect.

- Letter 707 to Nadezhda von Meck, 24 December 1877/5 January 1878:

No composer so scorned the requirements of the voice as Beethoven did: thus, he had no scruples about forcing a soprano in the choir (in his second mass) [Missa Solemnis] to sing a fugue, whose theme begins like this [...] Beethoven used human voices as if they were instruments.

- Letter 762 to Nadezhda von Meck, 16/28 February 1878, from Florence:

Of everything that I've seen, what impressed me most was probably the Medici Chapel in the Basilica of San Lorenzo. It is colossally beautiful and grandiose. It was only there that I first began to appreciate just how colossal Michelangelo's genius is. Indeed, I started to find in him a certain vague affinity with Beethoven. The same breadth and strength, the same boldness, at times bordering on ugliness, the same sombreness of mood. Incidentally, this thought may perhaps not even be new. In Taine I've read somewhere a very ingenious comparison between Raphael and Mozart. I don't know if anyone has ever thought of comparing Michelangelo to Beethoven?

- Letter 790 to Nadezhda von Meck, 16/28 March 1878, in which Tchaikovsky says that he could not understand why his benefactress did not like Mozart; he lists a number of his finest works:

Do you really not find anything beautiful in all this? True, Mozart does not grip one as profoundly as Beethoven; his sweep is not as broad. Just as in life he was a carefree child to the end of his days, so in his music there is no subjective tragedy of the kind which reveals itself so strongly and powerfully in Beethoven. However, this did not prevent him from creating an objectively tragic figure, indeed the most striking and powerful human figure ever portrayed through music. I mean Donna Anna in Don Giovanni...

- Letter 799 to Sergey Taneyev, 27 March/8 April 1878, who had criticized some passages of Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony as resembling 'ballet music':

I really do not understand what you mean by ballet music and why you are so against it. Do you call ballet music every cheerful tune with a dance rhythm? Well, in that case you must also be against most of Beethoven's symphonies, in which one continually comes across such melodies [...] Indeed, I just cannot understand why there should be something reprehensible in the phrase ballet music! After all, ballet music is not always bad; it can sometimes be very good (for example, Léo Delibes's Sylvia) [...] I simply don't understand why a dance tune cannot appear now and then in a symphony, even if only with a deliberate nuance of vulgar, coarse humour. I again invoke Beethoven, who resorted to this effect on more than one occasion. [...] Tchaikovsky then agrees that Taneyev was right in regarding his Fourth Symphony to be a work of programme music, but emphasizes that there was nothing wrong about this and that its general idea could be understood without knowing the 'exact' programme...] I wasn't seeking to express any new idea at all. Essentially, my symphony is an imitation of Beethoven's Fifth, that is I imitated not his musical thoughts, but the basic idea. What do you think — is there a programme in the Fifth Symphony? I tell you that not only does it have one, but that there can be no doubt whatsoever as to what it is seeking to express. The underlying idea of my symphony is approximately the same, and if you did not understand me, then all that means is that I am not Beethoven, as I have never been in any doubt about.

- Letter 1005 to Nadezhda von Meck, 5/17 December 1878, in which Tchaikovsky explains his views on 'programme music':

It was Beethoven who invented programme music, namely to some extent in the Sinfonia Eroica, but even more pronouncedly in the Sixth Symphony, the 'Pastoral'. However, Berlioz must be acknowledged as the true founder of programme music...

- Letter 1111 to Nadezhda von Meck, 16/28 February–17 February/1 March 1879:

By the way, in all my life I have only seen one true conductor — and that was Wagner, when in 1863 he came to Saint Petersburg to give some concerts, whereby he also conducted a number of symphonies by Beethoven. Those who haven't heard these symphonies in Wagner's interpretation cannot appreciate them fully and understand all their unattainable greatness.

- Letter 1578 to Nadezhda von Meck, 1/13–6/18 September 1880, in which he explains that he was studying the score of Mozart's Die Zauberflöte:

You cannot imagine, my dear friend, what wondrous emotions I experience when I become absorbed in his [[[Mozart]]'s] music! It has nothing in common with those painful delights which Beethoven, Schumann, Chopin, and indeed all music after Beethoven causes. The latter startles and fascinates, but it does not caress or lull one as Mozart's music does.

- Letter 3215 to Anton Arensky, 2/14 April 1887, in which Tchaikovsky makes some criticisms about Arensky's orchestral fantasia Marguerite Gautier (see also the entry on Verdi and Tchaikovsky's thoughts on La traviata):

Its beauty is external, conventional and contains nothing which grips one. Such beauty is not absolute beauty, but just prettiness (conventional beauty), and the latter (that is prettiness) is more of a deficiency than a virtue. Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, Mendelssohn, Massenet, Liszt,etc. are always pretty. Of course they, too, are masters in their own way, but their predominant trait is not the ideal towards which we should be striving, since neither Beethoven nor Bach, who is boring but still a genius, nor Glinka nor Mozart ever chased after conventional prettiness, but rather after ideal beauty, which often manifests itself in a form that sometimes, at a first, superficial glance, is not even beautiful.

- Letter 3651 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 26 August/7 September 1888, in which Tchaikovsky speaks of his admiration for the Russian poet Afanasy Fet (1812–1892), whose finest poems had a musical quality:

That is why Fet often reminds me of Beethoven, but never of Pushkin, Goethe or Byron or Musset. Like Beethoven, he is endowed with the power to touch such chords of our soul as are otherwise unattainable for those poets who, no matter how good they may be, are confined to the limits of speech.

- Letter 3675 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 21 September/3 October 1888, in which Tchaikovsky first discusses the poetry and aesthetic views of Afanasy Fet:

Can one say that there is any remplissage in Beethoven? In my view absolutely not. On the contrary, one marvels at how everything in the music of this giant amongst all composers is equally full of significance and strength, and at the same time, at the way he was able to restrain the incredible surge of his colossal inspiration and never failed to take account of the balance and roundedness of form. Even in his final quartets, which for a long time were regarded as the products of someone who had gone mad and lost his hearing entirely, the remplissages only seem to be so until one has studied them properly. Just ask some people who are particularly familiar with these quartets (for example, the members of some regularly playing chamber music ensemble) whether they can find anything superfluous in the C♯ minor quartet [Op. 131]. Almost certainly any such musician, unless he happened to be an old man who was brought up on Haydn, would be horrified if you suggested that he should cut or leave out anything. By the way, when talking about Beethoven, it is actually not his very final period which I have in mind. Now I challenge anyone to find in the extraordinarily long Sinfonia Eroica even just one superfluous bar, even just one such little passage which one could throw out! Therefore, not everything that is long is long-winded, prolixity is not empty talk, and brevity is by no means, as Fet argues, a prerequisite of absolute beauty of form. Referring again to Beethoven, who in the first movement of the Eroica erects a grandiose edifice with an infinite array of varied, ever new and striking architectonic beauties on the simplest and seemingly most insignificant motif — Beethoven, I say, knows how to astonish the listener sometimes with brevity and compactness of form. Do you remember, Your Highness, the andante in the B-flat major piano concerto [No. 2]? I cannot think of anything of greater genius than this very short movement, and I always become pale and shudder whenever I listen to it [... Tchaikovsky then criticizes the composers who came after Beethoven and tried to imitate him, especially Brahms, and argues that none of them could come up to the master himself...] This composer of genius, who liked to express himself in a sweeping, majestic, strong, and even sharp manner, had a lot in common with Michelangelo.

- Letter 3685 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 2/14 October 1888, in which Tchaikovsky defends the need for repetitions in music:

Beethoven never repeated whole sections of his works unless it was quite necessary, and very rarely did he not introduce something new when repeating, but he, too, realizing that his idea would only be appreciated fully if he expressed it several times in the same form, resorted to this device, which is intrinsic to instrumental music, and I must confess to Your Highness that I cannot understand why you do not like the way the theme of the scherzo in the Ninth Symphony is repeated so many times. For each time I so want it to be repeated again and again! After all, it is so divinely beautiful, powerful, original, and full of meaning! As for the longueurs and repetitions in Schubert, say, that's a different matter: in spite of all his genius, Schubert really does go too far in the way he endlessly keeps returning to the first idea (e.g. as in the andante of the C major symphony). No, that's quite different. Beethoven initially develops his thought fully and then repeats it, whereas Schubert almost seems to be too lazy to develop his ideas, and, perhaps as a result of his extraordinary richness in themes, he hastens somehow to present what he has begun so as to move on to the next bit. A swelling fount of luxurious, inexhaustible inspiration seems to have prevented Schubert from lovingly devoting himself to elaborate his themes carefully and thoughtfully.

In Tchaikovsky's Diaries

- Diary entry for 20 September/2 October 1886:

Probably after my death people will be interested to know what my musical passions and prejudices were, especially since I rarely expressed these in conversation.

I shall make a small start now and eventually, when I get to those composers who lived at the same time as me, I will also discuss their personalities.

I'll start with Beethoven, whom it is customary to praise unconditionally — indeed, one is supposed to cringe before him as before God. And so, what does Beethoven mean to me?

I bow before the greatness of some of his works, but I do not love Beethoven. My attitude towards him reminds me of how I felt as a child with regard to God, Lord of Sabaoth. I felt (and even now my feelings have not changed) a sense of amazement before Him, but at the same time also fear. He created heaven and earth, just as He created me, but still, even though I cringe before Him, there is no love. Christ, on the contrary, awakens precisely and exclusively feelings of love. Yes, He was God, but at the same time a man. He suffered like us. We are sorry for Him, we love in Him His ideal human side. And if Beethoven occupies in my heart a place analogous to God, Lord of Sabaoth, then Mozart I love as a musical Christ. Besides, he lived almost like Christ did. I think there is nothing sacrilegious in such a comparison. Mozart was a being so angelical and child-like in his purity, his music is so full of unattainably divine beauty, that if there is someone whom one can mention with the same breath as Christ, then it is he.

Speaking about Beethoven, I have stumbled across Mozart. It is my profound conviction that Mozart is the highest, the culminating point which beauty has reached in the sphere of music. Nobody has made me cry and thrill with joy, sensing my proximity to something that we call the ideal, in the way that he has.

Beethoven also caused me to shudder. But it was rather out of something akin to fear and painful anguish.

I do not know how to talk about music and so I cannot go into details. However, I will point out two details:

1) In Beethoven I like the middle period, occasionally the first, but at bottom I hate the final period, especially the last quartets. There are in these flashes, but no more. The rest is chaos over which there hovers, surrounded by impenetrable darkness, the spirit of this musical God, Lord of Sabaoth.

2) In Mozart..." [for the continuation see the separate entry on Mozart] [18]

Views on Specific Works by Beethoven

Bold references indicate particularly detailed or interesting references.

In Tchaikovsky's Music Review Articles

- Consecration of the House, overture, Op. 124 (1822) — TH 295, TH 311

- Fidelio, opera, Op. 72 (1814) — TH 269, TH 310

- Leonore Overture "No. 3" in C major, Op. 72b (1806) — TH 269, TH 294, TH 310

- Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58 (1807) — TH 285

- String Quartet No. 2 in G major, Op. 18/2 (1799) — TH 313

- String Quartet No. 8 in E minor, Op. 59/2 "2nd Razumovsky" (1806) — TH 273

- String Quartet No. 16 in F major, Op. 135 — TH 274 ("the swan-song of a dying genius")

- Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21 (1801) — TH 270

- Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36 (1802) — TH 287

- Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 "Eroica" (1804) — TH 268

- Symphony No. 4 in B-flat major, Op. 60 (1806) — TH 311

- Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) — TH 311, TH 316

- Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92 (1812) — TH 296

- Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93 (1812) — TH 259, TH 301

- Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 "Choral" (1824) — TH 301, TH 311

- Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61 (1806) — TH 305

- Violin Sonata No. 9 in A major, Op. 47 (1803), "Kreutzer" — TH 305

In Tchaikovsky's Letters

- Missa Solemnis in D major, Op. 123 (1822) — Letter 200 to Anatoly Tchaikovsky, 24 June/6 July 1870, in which Tchaikovsky describes his impressions of a music festival organized in Mannheim to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Beethoven's birth: "Amongst other things I heard for the first time Beethoven's Missa Solemnis, which is so very difficult to perform. It is one of the greatest works of music ever written." See also letter 707 to Nadezhda von Meck, 24 December 1877/5 January 1878 (quoted above under 'General reflections')

- Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major, Op. 19 (1795/1798) — Letter 3675 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 21 September/3 October 1888 (quoted above under 'General reflections')

- String Quartet No. 14 in C♯ minor, Op. 131 (1826) — Letter 3675 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 21 September/3 October 1888 (quoted above under 'General reflections')

- Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21 (1800) — Letter 2834 to Sergey Taneyev, 11/23 December 1885, in which Tchaikovsky looks forward to a concert in Moscow: "Can you imagine: I am rejoicing at the thought that I shall get to hear Beethoven's First Symphony. I myself didn't realize that I loved it so much. That's probably because it so resembles my god — Mozart. Don't forget that on 27 [sic] October 1887 we must celebrate the anniversary of Don Giovanni!".

- Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 "Eroica" (1804) — Letter 3675 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 21 September/3 October 1888 (quoted above under 'General reflections')

- Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 (1808) — Letter 799 to Sergey Taneyev, 27 March/8 April 1878 (quoted above under 'General reflections')

- Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 "Choral" (1824) — Letter 3685 to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, 2/14 October 1888 (quoted above under 'General reflections'); and Letter 681 to Sergey Taneyev, 7/19 December 1877:

In Vienna I heard Wagner's Die Walküre and was able to confirm my first impression from Bayreuth. If music really is fated to have in Wagner its principal and greatest exponent, then that is enough to cause one to despair. Can this really be the last word in music?! Will future generations really enjoy this pretentious, cumbersome, and unsightly nonsense, as we now take delight in [Beethoven's] Ninth Symphony, which in its time was also regarded as nonsense? If yes, then that's terrible.

External Links

Bibliography

- Чайковский и Бетховен (1912)

- Чайковский и Бетховен (1912)

- Чайковский и Бетховен (1960)

- Чайковский и Бетховен (1964)

- Tschaikowsky on the Eroica and Fidelio (1967)

- Tchaikovsky on Beethoven (1969)

- Tchaikovsky on Beethoven (1969)

- Peter Ilich Tschaikowsky (1972)

- Чайковский и Бетховен (1972)

- Бетховен или Чайковский? (1996)

- Чайковский. Бетховен. Вагнер - Христиан. Восприятие и истолкование музыкальный произведений (2000)

- Дирижерские пометы Чайковского в партитуре Девятное сиифонии Бетховена (2003)

- Бетховен и его время. История одного уникального литературного сочинения Чайковского (2003)

- Der "Gott Zeboath" der Musik. Dokumente zu Čajkovskijs Beethoven-Rezeption (2005)

Notes and References

- ↑ See also Tchaikovsky (1973), p. 196–197.

- ↑ The same point is made by Dieter Lehmann, in Čajkovsijs Ansichten über deutsche Komponisten (1995), p. 210.

- ↑ Tchaikovsky lost his mother when he was just a few years younger than Beethoven, and he writes very movingly about this in Letter 659 to Nadezhda von Meck, 23 November/5 December 1877, where he explains that, unlike his benefactress, religious feeling was very important for him, even if he was "convinced" that there was no eternal life after death: "However, conviction is one thing, and instinct and feeling another. Whilst I deny an eternal afterlife, it is with indignation that I reject at the same time the monstrous thought that I shall never see again some loved ones who are now dead. In spite of the triumphant force of my convictions, I shall never reconcile myself to the thought that my mother, whom I so loved and who was such a wonderful person, has disappeared forever and that I will never be able to tell her that even after twenty-three years of separation I still love her the same...".

- ↑ As Tchaikovsky observed in the above Letter 659 to Nadezhda von Meck, immediately after his thoughts about his mother: "And so you can see, my dear friend, that I am entirely made up of contradictions, and that, despite having reached maturity, I have not managed to settle on anything; I have not been able to calm my restless spirit either through religion or through philosophy. Truly, I think I should go mad if it weren't for music. Yes, for the latter really is the best gift from heaven for mankind while it strays in the dark. Music alone can clarify, reconcile, and set one at rest. But it is not simply a straw which one just about manages to clutch at. No, it is a loyal friend, protector, and source of consolation, and for the sake of music alone it is worth living in this world. After all, in heaven perhaps there won't be any music. So let us live on this earth for as long as we are alive!".

- ↑ Жизнь Петра Ильича Чайковского, том 1 (1997), p. 115.

- ↑ See Herman Laroche's Foreword to Музыкальные фельетоны и заметки Петра Ильича Чайковского, 1868-1876 (1898), i–xxxii.

- ↑ П. И. Чайковский в Петербургской консерваторий (1980), p 48.

- ↑ П. И. Чайковский в Петербургской консерваторий (1980), p 51. The manuscript of this exercise, however, seems to have been lost.

- ↑ This passage from Kashkin's memoirs is quoted in Tchaikovsky remembered (1993), p. 161.

- ↑ See Дни и годы П. И. Чайковского. Летопись жизни и творчества (1940), p. 480.

- ↑ See also letter from Nadezhda von Meck to Tchaikovsky, 6/18 October 1885.

- ↑ Letter 2778 to Nadezhda von Meck, 27 September/9 October 1885.

- ↑ П. И. Чайковский (1980), p. 116. Also quoted in Tchaikovsky remembered (1993), p. 161–162.

- ↑ See also Воспоминания о П. И. Чайковском (1980), p. 115.

- ↑ See also Letter 1081 to Modest Tchaikovsky, 24 January/5 February 1879.

- ↑ See also Letter 1115 to Nadezhda von Meck, 19 February/3 March–20 February/4 March 1879. In a diary entry for 1/13 July 1886, Tchaikovsky also looked back on his conversations with Tolstoy ten years earlier and recalled how the latter had been very keen to talk with him about music: "He liked to reject Beethoven and openly expressed doubts as to his genius. Now that is a trait which is not at all characteristic of a great man, since bringing down to the level of one's ignorance a genius who has been recognized as such by all, is typical of narrow-minded people." See Дневники П. И. Чайковского (1873-1891) (1993), p. 210.

- ↑ Letter 1408 to Nadezhda von Meck, 16/28–17/29 January 1880: "Beethoven and Michelangelo are very much kindred temperaments, don't you think?". See also the letter to Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich quoted in more detail above.

- ↑ Diary entry for 20 September/2 October 1886 in Дневники П. И. Чайковского (1873-1891) (1993), p. 212.